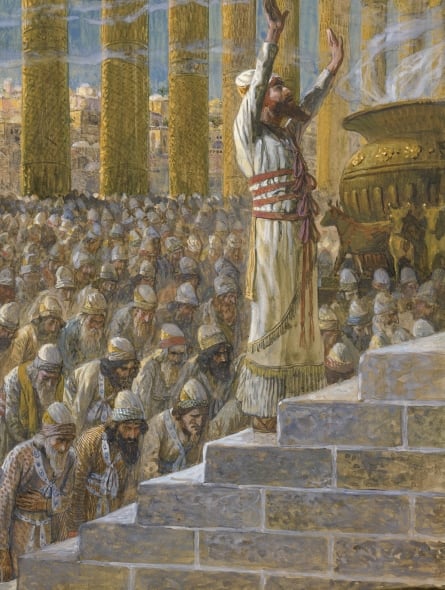

What It’s About: This is the prayer Solomon offered at the dedication of the temple in Jerusalem. It serves as a kind of a charter for the temple-king alliance, as it draws explicit and implicit connections between God’s dwelling place in the temple (or, at least the dwelling of God’s name there), and the righteousness and longevity of the Davidic line. The prayer has a kind of inward/outward structure (more on that in a moment), beginning with Israel and its particular concerns, and then expanding out to the greatness of God in the universe (verse 27) and the broader spectrum of humankind (41-43).

What It’s Really About: This prayer, placed on the lips of Solomon, was probably composed in two parts. The first part, reflected in the first part of the lectionary selection (verses 22-30), was probably Deuteronomistic. That is, it was probably composed by the writers who composed and compiled the Deuteronomistic history. It reflects the concerns of that tradition: faithfulness is rewarded, and unfaithfulness is punished. Here, the reader is reminded that God’s dwelling among the people is dependent on the actions of the people, and especially the king.

The second part of the prayer that is included in the lectionary, verses 41-45, was probably written later, and probably by someone living through the exile in Babylon. You can see a broadened perspective here: beginning in verse 41, there is a concern for those outside the nation of Israel and their perception of the Jerusalem temple and Israel’s God. Just after the section highlighted by the lectionary, beginning in verse 46 but continuing on, there is a reference to being carried off into captivity, signaling that the writer of this part of the prayer is viewing Solomon’s dedication of the temple through the lens of subsequent apostasy, destruction, and exile.

What It’s Not About: This is not a historical record. We shouldn’t be too scandalized by the idea that these words are not the transcript of Solomon’s prayer; that’s not how things worked in antiquity. Today, if someone important spoke at a big event, we might well get to read a transcript of the remarks. But in antiquity, writers were usually much more interested in reporting what someone important might have said or ought to have said in a given circumstance. This seems sloppy or even dishonest to us today, but we shouldn’t import our 21st century, post-enlightenment ideas into the past. The Deuteronomist, and later the exilic redactor, were helping Solomon say the right thing, in their way of seeing it.

Maybe You Should Think About: It’s interesting that the lectionary is working through so many themes of kingship and nation right as the 2016 presidential campaign begins to heat up. There is much to reflect on here. What is the proper role of religion in government? How much should national leaders be in the business of invoking God? Is the nation really the right venue for religious expression? Is God, as the Deuteronomist suggests, too large to be encompassed even in the universe, and therefore well beyond the confines of our national discourse? These might be interesting questions to explore, here in this moment between the time people become aware of the politics of 2016 and the time people become so partisan and entrenched that they can’t hear anything.

What It’s About: This is the conclusion (save for verses 21-23) of Ephesians, and it is a final exhortation to the reader. It’s couched in the language of combat, with references to shields, swords, breastplates, helmets, and even sensible shoes. These verses imagine a situation in which the reader is likely to face conflict, with both earthly and supernatural adversaries.

What It’s Really About: Verse 12 is one of the few in the bible that I prefer in the language of the King James Version, which warns about “powers…principalities…rulers of the darkness of this world.” This verse is a really nice synthesis, I think, between the conflict with earthly powers and the conflict with cosmic ones. It’s not that we can expect to enter into conflict with earthly rulers alone. And it’s not that this is simply a spiritual battle, to be waged on some ethereal plain. For Ephesians, the two are connected. The corrupt powers of this earth are corrupt insofar as they participate in a greater cosmic brokenness. Or, to put it the other way around, the powers of evil in the cosmos do their work through people and institutions that are far more earthly.

I can imagine the author of Ephesians (who was probably not Paul) writing this in a world where Roman authorities seemed very much like the agents of evil. People who come up against hegemonic systemic power–like early Christians, civil rights activists in the 1960s and today, religious and ethnic minorities around the world, people struggling for women’s rights, etc–often describe the systems they oppose this way. The people in a given system might not be evil; the average local Roman magistrate probably was a decent guy who went home to his family every night. But when acting within a system, people take on the role of “rulers of the darkness of this world.” It’s significant that Ephesians here is talking about “powers and principalities,” in the language of the KJV, and not bad people. Systems are the place where evil gets into the works. Systems are the conduits of cosmic brokenness.

What It’s Not About: Note that this really isn’t about offense. This person isn’t being outfitted for an invasion. The “whole armor of God” is mostly defensive. Aside from the sword (which is the word of God, hardly a violent thing in this context), the armor is all defensive. The author isn’t advocating an invasion here. This is simply a call to be prepared for the assaults that the powers and principalities will bring.

Maybe You Should Think About: This passage is often used for Vacation Bible Schools and children’s Sunday Schools, on the premise (I guess) that the boys will get excited about fake plastic swords and armor. But it would be really worthwhile to spend some time with these verses in a different, more nuanced, less martial way, talking about the kind of world they presuppose. What does the author want us to understand about the world? Do we have the same understanding of it? How are we to act in the face of systemic, cosmic injustice and evil? And, of course, what is the sword for?

What It’s About: This looks to us like eucharistic language. Jesus is talking to the disciples about eating his flesh and drinking his blood, and with the benefit of two thousand years of Christian ritual, we can recognize that as a reference to the Lord’s Supper. But verse 60 should remind us: this is a really weird thing to say. Imagine that you are standing there as Jesus says this. “Hey guys, the way to dwell in me, and for me to dwell in you, is to eat me. Also drink my blood.” That would be a really strange thing for someone to say. It would make no sense whatsoever. It would be offensive in several different ways, and gross in many more.

It is only with the benefit of hindsight that we can hear these words and say, “ah, yes, of course.” It’s worth remembering how shocking this would have sounded in the first century.

What It’s Really About: This discourse becomes a kind of litmus test. The weird, offensive, gross words that Jesus said here caused some to leave him (verses 64, 66). And who can blame them? For those who stayed behind, the reasoning seems to have been that Jesus’ words were so powerful, his being so compelling, that they had no choice but to stay (verses 68-69). It’s interesting that this proto-eucharistic language was a way to winnow the truly faithful from those who were only along for the ride. It puts an interesting spin on the notion of communion, especially so early on in the Christian tradition.

What It’s Not About: It’s not about inclusion, as much as it pains me to say it. These verses recognize an inside/outside dynamic: either you can tolerate this kind of talk, or you can’t, and if you can’t, it’s better to get out. That’s disheartening in some ways, but it’s also a reality of social groups. Every group has boundaries; that’s why it’s a group. I’ve recently seen some people question the “everybody welcome” attitudes of progressive Christianity in this way. Really? Everybody? And if there are some kinds of people that aren’t welcome, who draws that line? These are really hard questions.

Maybe You Should Think About: I sometimes get frustrated with the traditional communion liturgies. Take the Great Thanksgiving, for example. It’s beautiful, and grand, and very inspiring. It ties up a lot of loose ends, and it makes the whole thing make sense. But of course it has almost nothing to do with what Jesus said. It’s a core of language going back to Jesus, surrounded by years of accumulated theology. What would happen if we invited people to the table the way John 6 does? “Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me, and I in them. Please come forward through the center aisle.” Just like that.

Then, we could reclaim some of that shocking, visceral (literally) quality to the words of Jesus. We might not be so eager to spring up from our pews then. We might not be so excited to take that piece of bread. And maybe that’s how we are supposed to feel. Maybe it’s not supposed to feel easy.