What It’s About: Here we meet Lydia, an important figure in the first generation of Christians. Lydia was a dealer in purple cloth, which might suggest that she was somewhat well-to-do. The introduction to Lydia takes place outside the city gate of Philippi, which was a sizable city. It’s interesting that it was know where there was a “place of prayer,” even in a foreign city. What kind of “place of prayer” was this? A quiet, uncrowded place? A shrine? A synagogue? The text is vague on this count, which might be purposeful.

What It’s Really About: This passage is really useful for illustrating the kinds of informal networks that characterized earliest Christianity. Paul, here, has traveled to a new place, and he is able to sink roots into the place immediately, by making the acquaintance of a few key people. Lydia just happened to be nearby, and she heard his message, and became a very important figure in the church. This is in contrast to the way Acts normally describes Paul’s missionary activity, which was that he went to a new place and went immediately to the synagogue, where he was inevitably rejected, causing him to seek gentile converts. This way of thinking about Paul’s missionary activity ends up being pretty anti-Jewish; the whole thing hinges on the rejection of the Jews. In his own letters, though, Paul seems to take a different approach, starting with the kind of informal meetings that he has here in Acts 16. It’s worth thinking about the difference that this makes…how it matters what kind of context surrounds his meeting with Lydia.

What It’s Not About: This passage contains a shift in narrative voice. Verse 9 is “they” language, the 3rd person plural narration that is characteristic of most of Acts. But starting in verse 10 we get one of the “we” sections, which are found here and there in Acts. Scholars have debated what to make of this shift in voice. Is Luke here giving his own experiences? Is he working from someone’s travel diary? Is he just being sloppy with his writing? Some see a lot of meaning in the shift from “they” to “we,” and others don’t, but the “we” language does give this passage a lot of immediacy and urgency.

Maybe You Should Think About: Scholars have struggled to understand how Christianity spread in its earliest days. How did the religion of a rag-tag band of people from the hinterlands of the Roman Empire, whose leader had been executed, come to spread throughout the Mediterranean basin and become the religion of that Empire within a few centuries? The kind of story related here was undoubtedly important to that story…a chance meeting of Paul with a person who was receptive to the message set the scene for a whole new sphere of missionary activity, as Paul’s ministry was now spreading into Europe. This story gives us a glimpse of how Christianity might have spread–informally, but inevitably, as the new faith filtered out into the Empire.

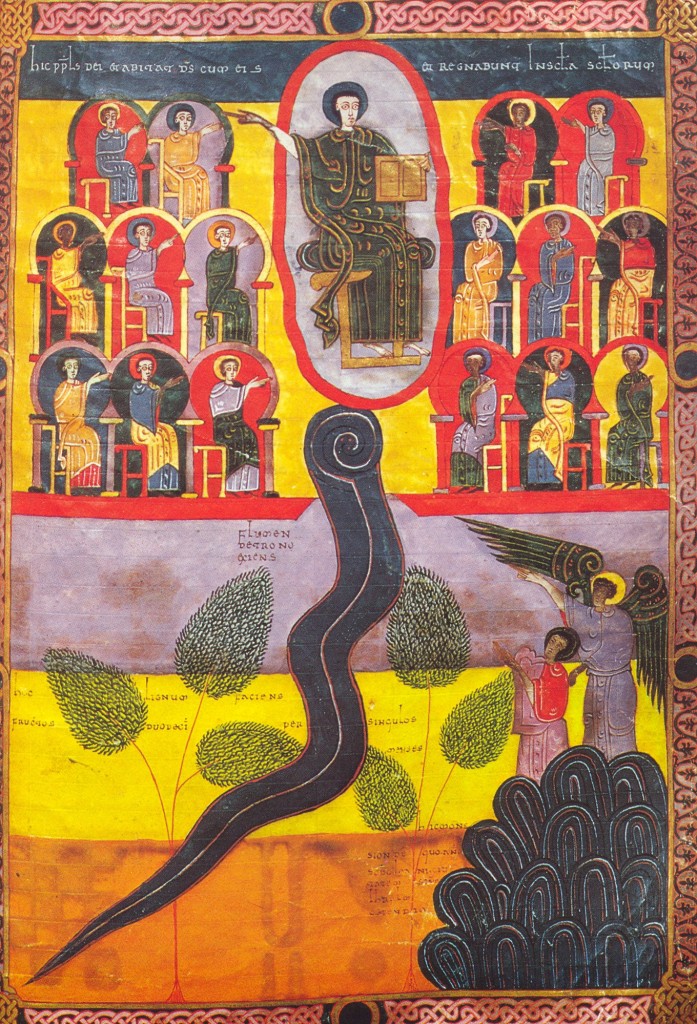

What It’s About: From the top of a high mountain, John the revelator is shown the new Jerusalem coming down out of heaven. Already we should pause; most interpretations of Revelation presume that it is about the destruction of the world, but here we have a mountain, and by implication a valley below, and a city that is going into that valley. The city itself is not some new heavenly place, but it is Jerusalem, made new, to be sure, but recognizable as Jerusalem. This is an extremely earth-positive image, quite in contrast to the cosmos-destruction-porn that passes for exegesis of Revelation these days. Revelation doesn’t envision the extinguishing of the world; it envisions the world made new. Here, in Revelation 21 and 22, we see the fruits of the labor of Revelation–the “revealing” at the end of Revelation. It is a world remade, not a world destroyed.

What It’s Really About: This passage owes a lot to the Hebrew Bible and other ancient Jewish texts. My Harper-Collins study bible has notes on this passage pointing to Ezekiel 40-48, Isaiah 54:11-12, Tobit 13:16-17, and the Temple Scroll from Qumran. In other words, Revelation is not so much an innovation in imagining the way God will redeem the world as it is a continuation of a very long tradition of understanding God as concerned with the redemption of the cosmos. John the revelator, in other words, is standing in a long tradition–a Jewish tradition–of understanding that God is already remaking the world, in a very literal worldly sense, in a way that preserves it and transforms it into something more godly.

What It’s Not About: It’s not about heaven on a cloud somewhere. This is one of the most remarkable misunderstandings of modern Christianity: that heaven exists elsewhere, abstracted from this world and cosmos. There is this sense that the afterlife (both of persons and the human race generally) takes place far away in an ethereal realm. But this is not at all what the bible describes. The bible is quite terrestrial in its heavens; heaven is always coming to earth, and things take place “on earth as in heaven,” not “in heaven instead of on earth.”

Maybe You Should Think About: Springtime is the season of the remaking of all things. The seasons go through a cycle of life and death, decay and rebirth. That seems to be the pattern we see in the bible, which is not surprising, since it was written by people who were radically connected to seasonal rhythms. Time was more circular for ancient people than it is for us; things were being reborn and remade all the time. Maybe we should think about how to reclaim something of that legacy.

What It’s About: What happens when Jesus is gone? That question must have consumed Jesus’ disciples and the first generation of his followers. Anxiety about that inevitability is evident in a few places in the New Testament; here, in John, Jesus addresses it forthrightly. He promises a “paraclete,” a kind of advocate or (if we’re being literal) attorney, who is also the Holy Spirit. Those two terms–paraclete and Holy Spirit–alongside each other here suggests that John knew about those two ways of describing the presence of God that would remain after Jesus’ death. They are two ways of describing functions of God’s presence–as protector/advocate and as comforter and inspirer.

What It’s Really About: It would be anachronistic to think of this passage as trinitarian. The Trinity was a later theological development that doesn’t really belong to the period of the New Testament. But there are predecessors of the Trinity in the New Testament, and understandings of God and God’s presence that point the way forward to the later trinitarian formulations. This is one of them; it’s a way of describing an aspect of God’s presence that will come after Jesus. It’s also, though, an old way of describing God’s presence, with roots deep in the Sophia traditions of the Hebrew Bible, and the many times that God was described as a comforter, guardian, and inspirer.

What It’s Not About: 14:31 is a bit beyond the scope of this passage, but isn’t it interesting? Look at its last sentence: “Rise, let us be on our way.” Then, in 15:1, Jesus keeps talking as if there had been no interruption. What a fascinating little inclusion? Why is it there? Was this initially part of a narrative that included some kind of action after 14:31? Was 15:1 and the following material inserted later? “Rise, let us be on our way” seems like an abandoned narrative cue.

Maybe You Should Think About: What’s the difference between an advocate and a spirit? How do we think about the third member of the Trinity today, and do we shortchange one or both of these understandings in the way we talk about it today?