What It’s About: This passage from Acts narrates an episode in one of the most urgent crises of the early Christian movement: the problem of gentile inclusion. There are roots of gentile inclusion sunk deep into the Jewish tradition, and there had been a sense in Jewish scriptures and practices that gentiles were, should be, or would be included in the worship of Israel’s God. These roots helped to feed the early Christian movement, which was of course an expression of second-temple Judaism. In the way the current New Testament tells it, the main actors in this crisis in the early church were Paul and the Jerusalem Christians, which included people like Peter and James. Paul was obviously all-in on gentile inclusion; he felt that the event of Jesus meant that God’s family had been opened to everyone, even those outside of Israel. The Jerusalem faction, though, seemed resistant to this, and Peter’s vision seems to narrate a kind of breakthrough compromise in that dispute.

What It’s Really About: Peter’s vision is cast in terms of an epiphany or a revelation. In his vision, Peter sees a sheet (which is strange) coming from heaven, with a variety of animals on it. He’s told to “kill and eat” (also kind of jarring), but he protests: many of the animals on the sheet are not acceptable to eat under Jewish law. But the voice told him to accept what God had made. So it came to pass that Peter changed his mind on eating unclean foods, and therefore on eating with gentiles. It’s interesting that the story is told somewhat out of order; the vision had already taken place by the time the passage begins, and it is related in the service of explaining Peter’s new eating habits.

What It’s Not About: Maybe it happened this way, but I tend to see this story as a kind of concession–a convenient, face-saving vision–to the kind of Christianity preached and practiced by Paul. I think this is evidence that Paul won the day, even among the Jerusalem crowd, and so Peter had to adjust his position, and ascribe it to divine instruction. Or, perhaps, Luke had to account somehow for Peter coming out on the wrong side of the debate, and so in Acts he has Peter’s change of heart come at the instigation of God.

Maybe You Should Think About: The church has spent a lot of time being (in my opinion) wrong about a lot of things, only to see the error of its ways later on. The roles of women, the inclusion of GLBT persons, the problem with divorce, and so on–on many issues the church has held a (sometimes) well-intentioned position only to change it down the line. People who hold to the old position often chalk this up to political correctness run amok (Stanley Hauerwas is one who sometimes says this). But I see this story of Peter’s vision as solid evidence that sometimes God wants us to change our minds about things, and to do so is not an act of apostasy, but an act of faithfulness. “God is still speaking,” as the slogan goes…and it would be wise to listen.

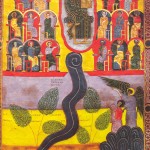

What It’s About: This is a beautiful passage from near the end of the Apocalypse, which features a vision of the aftermath of that book’s various struggles and conflicts. It is often assumed that the outcome of Revelation is annihilation; popular riffs on the eschaton (like the Left Behind series) see the world as being destroyed. But Revelation ends in a pretty different place–the remaking of heaven and earth, and not in a generic, abstract way, but in a very concrete (pun intended) way. Jerusalem–in all its city-ness–is part of the future. And, most promisingly, “the home of God is among mortals.” God is intimately bound up with us, and this place, in which we find ourselves. The world is not disposable or irrelevant, as many strains of Christianity have often assumed or even argued. The earth is integral to God’s plan.

What It’s Really About: This passage is part of a larger sweep (in chapters 20 and 21) of the telos of the book of Revelation, but also of the cosmos. It’s the payoff to all the sound and fury of the earlier chapters. And I think it’s connected to the notion of the Kingdom of God (or Kingdom of Heaven) found in the gospels. The message of that narrative is distilled to “the kingdom is at hand, and the kingdom is among you,” which resonates quite nicely with the vision of a new Jerusalem. New Jerusalem, yes–but also new Peoria, new Dubuque, new Sausalito, new Charlotte. The world is being remade, at God’s direction, and we are invited to be a part of it, because the home of God is among mortals. That’s pretty powerful.

What It’s Not About: Christianity owes a lot to Platonism, including a lot that is really valuable. But one legacy of Platonic thought is dualism, which usually constructs pairs of things (light/dark, good/evil, life/death, etc) and privileges one of those things over the other. Heaven/earth is one of the most powerful of these, and earth, in that dualism, is de-valued. So Christianity has often dismissed the world as fallen, bad, sinful, and ultimately useless. This passage is a valuable corrective to that.

Maybe You Should Think About: What does a commitment to this world look like? What, if God dwells among mortals, do we do about God’s dwelling place? Earth Day is upon us…this could be the seed for a really good sermon.

What It’s About: “That you love one another.” That’s pretty much what it’s about. Jesus is announcing in this passage that he is going on to another place, where his disciples cannot go, and the instruction he pairs with this news is “love one another.”

What It’s Really About: It’s about identity. Look at verse 35. This is supposed to be the sign that you’ve encountered some Jesus-disciples: that they love one another. That’s a pretty strong identifying feature, and if that’s supposed to be the identifying feature, then that’s a pretty strong commandment.

What It’s Not About: It’s not about selfishness, is it? The prosperity gospel, in all its forms, founders on this passage. Sure, you could argue about “love yourself so that you can love others.” But that’s willfully misreading the text. Jesus here is describing a communal ethic that is profoundly focused on the other, not the self.

Maybe You Should Think About: Does this loving-one-another signal something about that new heaven, new earth, and new Jerusalem above? How does all that fit together? Does loving one another help bring on the remaking of the world?