Jeremiah 2:11-12, 22-28 and/or Exodus 32:7-14

What It’s About: These are both stories about God’s wrath and the limits of that wrath. In the Jeremiah passage, the prophet is promising a judgement from God, stronger than a rebuke, but not a “full end.” In the Exodus passage we have the famous incident of the golden calf, where God intends to wipe the people out but Moses talks God out of it. In both cases God is presented as wrathful and even hotheaded, but in both cases God settles for something short of a full destruction. God is patient, it seems, but only reluctantly so.

What It’s Really About: The Exodus story is one of several stories of God moderating divine wrath after a conversation with a human. These stories are always a little jarring; they give the impression that Moses (or Abraham, in Genesis 32) is more forgiving than God, and that human ethics are more flexible than divine ones. Often people (especially, in my experience, people rooted in the theology of the Reformation) will respond that God must be wrathful and judgmental, because God is utterly just, and therefore God cannot tolerate injustice. This always strikes me as overly confident about what God can and cannot do. More likely, I think, is that stories like this one and the one in Genesis 32 are literary devices designed to underscore the egregiousness of human behavior and the mercy of God in spite of God’s righteous anger. God, here is anthropomorphic, getting angry before calming down again, and preparing to stalk away before remembering what’s important about staying.

What It’s Not About: This is not about individual salvation. One of the great gaps between the biblical tradition and the way Christianity works today is the notion that it’s all about the individual. Christianity portrays faith as a matter of personal belief, and possibly personal ethics. But in the biblical tradition (both testaments), religion is far more communal in nature. Here, God threatens the destruction of all, sparing only Moses. Surely there were a few righteous sprinkled into that mix? But salvation and destruction are for “my people,” as a whole, not just individual persons. The people are responsibly collectively for the best and worst among them. That’s a very different ethics than the kind espoused by most Christianity today.

Maybe You Should Think About: Why do biblical writers portray God this way–as a wrathful deity who judges the people as a whole, and turns from anger when prompted by special human beings like Moses and Abraham? Does this way of thinking of God make sense to us? Why or why not?

What It’s About: This is from the beginning of 1 Timothy, where the author (who was not Paul; scholars are fairly confident that the Pastoral Epistles are incorrectly attributed to Paul) is giving thanks for lifting him out of a life of sin. Here, salvation is individual, to some extent. The author was apparently a prodigious sinner, but God has brought the author to a better way. You can think of this sentiment as a more individual sequel to the Jeremiah and Exodus texts above; this is what happens when God exercises salvation instead of wrath.

What It’s Really About: This passage follows verses 3-11, which deal with false teachers and a list of bad behaviors that the law is designed to save us from. These lists of bad things, called “vice lists” by scholars, are common in Paul’s letters and in pseudo-Pauline literature like 1 Timothy. Usually in Paul’s letters they are constructed from a Jewish standpoint (Paul was, and remained, Jewish) as a critique of Gentiles; Jews had certain stereotypical views of Gentiles as depraved, sinful, and unrepentant. From the Jewish perspective, Gentile behavior is exactly the kind of thing the law was supposed to prevent. Here in 1 Timothy this message is a little muddled, since it’s borrowed from authentic Pauline letters to give this one a sense of authenticity. But the kernel of the message, in verse 9, is that it is not the innocent who need the law but the guilty; that aligns nicely with the Jeremiah and Exodus texts above. This is a positive view of the law–something Christians would do well to acknowledge.

What It’s Not About: This is definitely not about Donald Trump, but I can’t help but think of the presidential candidate when I read verse 15 (and 3:1, 4:9, 2 Timothy 2:11, and Titus 3:8). “This saying is sure” is a common rhetorical throwback for the Pastoral Epistles, and it reminds me a lot of Trump’s habit of saying “believe me” when making claims on the campaign trail. “This saying is sure” is a way of bringing the reader in on the claim about to be made; it’s a way of establishing trust in the words before they are even read. Trump does the same thing with his “believe me;” it’s a way of inviting the hearer to trust him. For what it’s worth, scholars sometimes see these repeated insistences that the speaker is speaking the truth as telltale signs of dishonesty; perhaps, some scholars say, the writer of the Pastoral Epistles keeps saying “this saying is sure” because he wants to dispel doubts about the authorship of the letter.

Maybe You Should Think About: This is ostensibly a letter to a younger colleague; Timothy (at least as portrayed in this letter) was a kind of understudy to Paul. What, then, do the appeals to the law and the call to turn from bad behavior imply? Was Timothy notoriously badly behaved? Is this just the kind of thing older people think about younger people (“kids these days”)? Why include this in a letter that’s supposed to be about encouragement and advice?

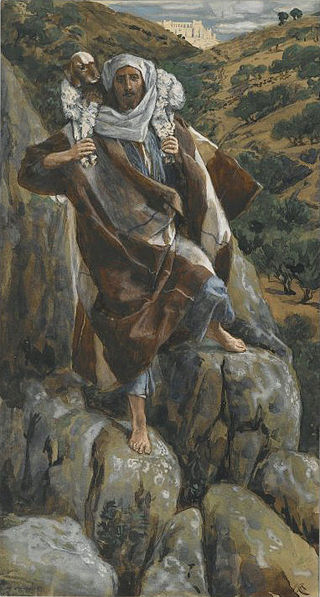

What It’s About: These are the first two of what I think of as a three-part parable. Luke (along with the other gospel writers) is intentional about the construction of the gospels; they put things together in ways that are mutually beneficial. (Or, possibly, Jesus put these stories together and Luke is simply conveying them that way, though if that were the case we might expect Mark to do the same). These stories–the parables of the lost sheep, the lost coin, and the lost son (also known as the prodigal son)–are meant to parallel each other and interpret each other. They follow a common pattern: something precious is lost, the precious thing is found again, and a celebration ensues.

What It’s Really About: My New Testament professor at Vanderbilt, Amy-Jill Levine, provided an interpretation of the parable of the lost sheep that has stuck with me ever since, and that I find comically disturbing. In the parable of the prodigal son, the son’s return prompts a party, in which a calf is slaughtered and eaten. In the parable of the lost coin, the woman finds the coin and then invites her friends over to celebrate (thereby probably spending the coin on the party). In the parable of the lost sheep, then, when the lost sheep is found and the person “calls together his friends and neighbors” to rejoice with him, guess what was on the menu? That troublesome sheep probably was. Spend the coin, kill the calf, and…see you later, wandering sheep.

What It’s Not About: “There will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance” is pretty different than the “ok fine I guess I won’t destroy them ALL” model of divine justice we saw in Jeremiah and Exodus. People tend to chalk this difference up to the difference between the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, even going so far as to talk about “the wrathful God of the Old Testament” and “the God of love found in the New Testament” as though they were different Gods. But if you believe that they are one God, what is to account for this difference? Is it a difference in God, or a difference in the way God is portrayed? And what accounts for the difference in portrayal? And if you read Jesus’ words as the words of a Jew of the first century (which is precisely what they are), what does that say about the development of Jewish notions of God over the centuries? Think of it that way–this isn’t a Christian innovation (that God is fundamentally patient and loving); it’s a Jewish innovation. Where did it come from?

Maybe You Should Think About: If the woman who lost the coin spends it when it’s found, and if the person who lost the sheep eats it when it’s found, and if the father kills the calf when his son returns, what exactly does that celebration in heaven look like when one sinner repents?