What It’s About: This is the story of Saul–who would become Paul–and his experience on the road to Damascus. It’s a dramatic story of radical change; Saul goes from wanting to persecute those who “belonged to the Way” (there is no “Christianity” yet) to wanting to join them, all in the course of a few verses. It’s not really correct to talk about this as a “conversion,” since Paul doesn’t “convert” from one religion to another, and anyway there is no Christianity to convert to yet. But it’s a pretty impressive turnaround, and Paul’s transformation is pretty amazing. It’s also about the ways the other ones who “belonged to the Way,” like Ananias, were skeptical of Saul’s new outlook–and understandably so. Was he trying to infiltrate their group? Was he a spy or a plant? What were his intentions? It would be difficult to welcome into your group the very person who was eagerly persecuting you.

What It’s Really About: As it happens, I’ve just spent the last two days at the Rocky Mountain/Great Plains regional meeting of the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Biblical Literature, held at my home institution of the Iliff School of Theology. I heard a really interesting paper at that meeting about the way this part of Acts uses certain parts of the book of Tobit, given by John Sehorn of the Augustine Institute. Luke (which is the name scholars give to the author who wrote both the gospel of Luke and Acts) borrows liberally from Tobit in writing this account of Paul’s experience, including the details of the scales falling from the eyes (the NRSV says “whiteness” in chapter 3). That Luke should do this maybe shouldn’t surprise us, since he’s very up front about his role as a historian who sorts out sources and creates a narrative out of them (Luke 1:1ff). But take a look at Tobit, and try to look for the ways Luke has used it in his account of Paul’s experience.

What It’s Not About: In Galatians 1:15-2:1 (and the surrounding material) you can see Paul’s account of this experience. It seems that Paul has heard an account of the story that resembles Luke’s version (he probably hasn’t actually read Acts, since it probably hadn’t been written yet). Paul tells it very differently–in a way that de-emphasizes Paul’s reliance on the Jerusalem disciples, and increases Paul’s reliance on God. This is actually really pivotal for Paul’s identity as an apostle: he is very clear, in Galatians and elsewhere, that he is an apostle sent by God and trained by God. Acts never calls Paul an apostle; the way Acts tells it, Paul is subordinate to the authority of the Jerusalem church.

Maybe You Should Think About: The way a “call story” is told tells us a lot about what that call means, or what we’re supposed to think it means. What difference does it make whether Paul goes straight to the disciples in Jerusalem to get trained by them and to get their approval? Or whether the spirit teaches him everything he needs to know? What’s the source of authority in each case, and how does it affect the authority of Paul’s own ministry, and ultimately his own letters?

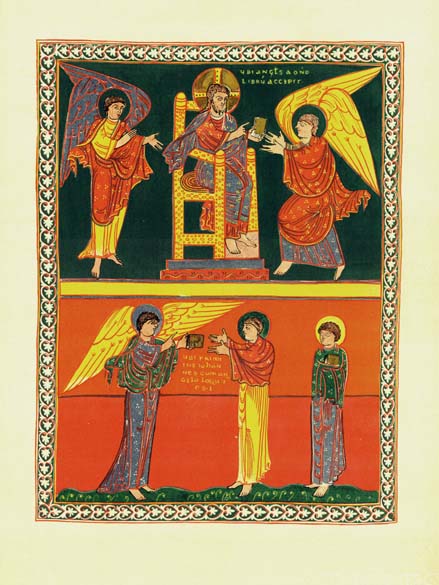

What It’s About: This is from a section of Revelation that depicts a heavenly scene of glory and praise. Revelation skips around a lot–both in terms of time and space. Here we find ourselves in the presence of God and the Lamb (who we can understand as Jesus Christ), and in the presence of a bunch–“myriads of myriads”–of angels, living creatures, and elders. All of those myriads are praising the Lamb and extolling his worthiness. It’s not entirely clear, at least to me, how we are supposed to understand this episode within time. Is this what is going on in the present-time of the book? Or is this in the future? Either way, it’s probably meant to signify an ideal state of things, and to emphasize the godly nature of the Lamb. There are echoes of Ezekiel here, in the throne and attendant angels, and so the imagery all points to Jesus (as Lamb) being exalted and praised on the same level with God.

What It’s Really About: Revelation is an apocalypse, in terms of genre–in fact, “revelation” and “apocalypse” translate the same Greek word. The genre of apocalypse doesn’t mean that it’s a big disaster. And it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s about the end of time or the end of the world, although certain interpretations of apocalypses point that way. Apocalypse is about the unveiling of things, and imparting otherworldly understanding to this-worldly people. It’s a little window into another world, in some ways. That’s what the time-skipping and space-skipping does: it gives us a glimpse into things we wouldn’t otherwise see. Here, by showing us that the Lamb (Jesus) is being praised in heaven in the same way God is, the passage equates Jesus with God, or at least puts Jesus into the same status as God.

What It’s Not About: One of my favorite things on the internet these days is the KJVBot, a creation of scholar Timothy Beal. KJVBot is a Twitter account that tweets out computer simulations of utterances from the King James Bible. How it was created is a fun story–it involves some creative coding–but essentially, the Bot takes real King James language and makes King James-like things out of it. A lot of the KJVBot’s tweets end up sounding a lot like Revelation. It’s interesting to think about why. What is so distinctive about Revelation, and what does that distinctiveness have to tell us about the way the Bible uses language?

Maybe You Should Think About: The “every creature” language in verse 13 is interesting, as we come nearer to Earth Day at a time when climate change is becoming more and more apparent. What is the link between the earthly realm and the heavenly one? Here we see that they are connected, and in fact that’s one of the major concerns of the whole book of Revelation. This world is not disposable for Revelation (see chapter 21, where things are made new, but not eradicated wholesale). The world is intricately connected to what goes on in heaven, and the creatures of the earth join in the praise of the Lamb and, really, in the presence of the Lamb. In the bible’s most earth-destroying book, creation still gets a major role to play. The world is not disposable.

What It’s About: John 21 is one of my favorite chapters of the bible. It’s described in my Oxford NRSV as an “Epilogue,” which is probably correct. But it’s also appropriate to think of it as an alternative ending, probably added at a later date than the rest of the gospel. (Look at the end of chapter 20; doesn’t that feel like a conclusion?). This epilogue has Jesus making another post-resurrection appearance–with the familiar pattern of no one recognizing him–and imparting teaching to his disciples. In particular, Peter is singled out for attention, as someone who doesn’t seem to have the full trust of Jesus and someone who can’t seem to muster the appropriate response to Jesus’ questions. It’s a poignant and beautiful scene, and one that lays the groundwork for the post-gospel story really well.

What It’s Really About: The heart of this passage is Jesus’ threefold question to Peter: “Do you love me?” Much has been made about the Greek verbs in this passage; in the first two questions Jesus uses the Greek verb based on the word “agape,” and in the third a verb based on the word “philos.” In all three cases, though, Peter responds with the word from “philos,” even when Jesus asked it in the “agape” way. Some see this as a failure on Peter’s part; Jesus was asking about one kind of love, and Peter was only able to muster a lesser kind of love. I like this interpretation, but some scholars see this as an over-reading of the importance of Greek verbs. In either case, Peter doesn’t come off too well here. If someone has to ask you a question three times, they don’t really trust or feel satisfied with your answer. That this is put into the context of “feeding” “sheep” makes it all the more powerful; Jesus is asking Peter to be a pastor, even as he seems doubtful of Peter’s ability to do it. Lots of ministers and lots of other kinds of people who serve others will recognize the tension: the enormity of a call partnered with the inadequacy of the called.

What It’s Not About: It’s striking how much this is focused on Peter, and not the rest of the disciples. That’s especially striking in the gospel of John, which has a special concern for the “disciple whom Jesus loved.” That disciple makes an appearance in verses 20-25, just after this passage, which close the gospel. It’s remarkable that here at the end of John, Peter is getting all of the attention.

Maybe You Should Think About: This makes for a good meditation on leadership. People who are somehow responsible to other people–pastors, yes, but also teachers, committee members, counselors, deacons, bosses, and all kind of people–often feel a disparity between the thing they’re asked to do and the tools they have to do it with. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed at the task of a big job. Peter, here, was being asked to do something pretty huge: “feed my sheep.” And even as he was being asked to do it, he was failing at it, unable to respond to Jesus in a satisfactory way. Peter, of course, turned out ok, despite his shortcomings, and we can take some comfort in that. Maybe use this passage as a way to talk about our inherent shortcomings as human beings, as related to the callings we have in the world?