In his 2005 Christmas encyclical, Deus caritas est, Benedict XVI explains why love has to be understood as both eros and agape , as ascending and descending love. He notes early on that the Bible rarely uses the word eros , arguing that “the tendency to avoid the word eros , together with the new vision of love expressed through the word agape, clearly point to something new and distinct about the Christian understanding of love.”

As he notes, “these distinctions have often been radicalized to the point of establishing a clear antithesis between them: descending, oblative love— agape —would be typically Christian, while on the other hand ascending, possessive or covetous love — eros —would be typical of non-Christian, and particularly Greek culture. Were this antithesis to be taken to extremes, the essence of Christianity would be detached from the vital relations fundamental to human existence, and would become a world apart, admirable perhaps, but decisively cut off from the complex fabric of human life.”

The detachment of love from eros is at the heart of the Enlightenment critique of Christianity: “In the critique of Christianity which began with the Enlightenment and grew progressively more radical, this new element was seen as something thoroughly negative. According to Friedrich Nietzsche, Christianity had poisoned eros , which for its part, while not completely succumbing, gradually degenerated into vice. Here the German philosopher was expressing a widely-held perception: doesn’t the Church, with all her commandments and prohibitions, turn to bitterness the most precious thing in life?”

The issue at stake in debates over eros and agape is not about the definition of love narrowly construed; it is about the gospel’s relation to culture and human experience as a whole. If Christian faith is eros -denying, then it is an enemy of life.

Yet neither in the Old or New Testaments do we find an attack on eros as such. Instead, the Old Testament “declared war on a warped and destructive form of it, because this counterfeit divinization of eros actually strips it of its dignity and dehumanizes it. Indeed, the prostitutes in the temple, who had to bestow this divine intoxication, were not treated as human beings and persons, but simply used as a means of arousing ‘divine madness’: far from being goddesses, they were human persons being exploited.”

In short, “eros needs to be disciplined and purified if it is to provide not just fleeting pleasure, but a certain foretaste of the pinnacle of our existence, of that beatitude for which our whole being yearns . . . . the way to attain this goal is not simply by submitting to instinct. Purification and growth in maturity are called for; and these also pass through the path of renunciation. Far from rejecting or ‘poisoning’ eros, they heal it and restore its true grandeur.”

This grandeur is not achieved by the contemporary materialism notion that humans are bodies and nothing more. In fact, Benedict argues that the obsession with the material body turns against the body. True love captures the whole man, body and soul, and this body-soul unity in love is depicted most vividly in the Song of Songs.

Benedict notes that “in the course of the book two different Hebrew words are used to indicate ‘love.’” The first, plural term (dodim) suggests “a love that is still insecure, indeterminate, and searching. But this is replaced “by the word ahabà , which the Greek version of the Old Testament translates with the similar sounding agape , which . . . becomes the typical expression for the biblical notion of love. By contrast with an indeterminate, ‘searching’ love, this word expresses the experience of a love which involves a real discovery of the other, moving beyond the selfish character that prevailed earlier. Love now becomes concern and care for the other. No longer is it self-seeking, a sinking in the intoxication of happiness; instead it seeks the good of the beloved: it becomes renunciation and it is ready, and even willing, for sacrifice.”

Eros may initially be desirous in a self-serving way. As it is disciplined, however, it becomes shaped into agape , love that realizes the grandeur of love because it is focused on a single object of love and because it is permanent. Yet eros is never left behind: “man cannot live by oblative, descending love alone. He cannot always give, he must also receive. Anyone who wishes to give love must also receive love as a gift.”

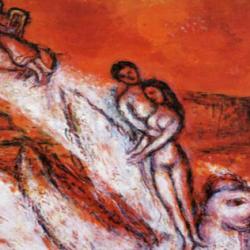

Love is a ladder to heaven, and on that ladder is the two-way traffic of eros-agape: “In the account of Jacob’s ladder, the Fathers of the Church saw this inseparable connection between ascending and descending love, between eros which seeks God and agape which passes on the gift received.”