There is a glory of the sun, of the moon, and of the stars, Paul says. And star differs from star in glory.

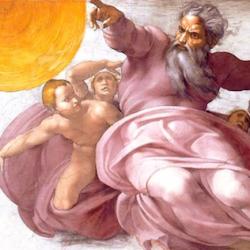

He’s talking about resurrection, but Joel Salatin (The Marvelous Pigness of Pigs) wants to apply the principle to every created thing: “Glory speaks to uniqueness; what makes God God, you you, and me me. And a pig a pig.” He wants us to see the glory of the pig: “Respecting the glory of each encourages a respect for the glory of all,” since everything points “toward the Godness of God” (19).

Our farming methods don’t respect the glory of pigs. Farmers “cut off the pigs’ tails – called docking – to intentionally make them sore and tender.” Why? To keep pigs from devouring each other”: “When pigs in . . . confined quarters can’t act out their pigness like rooting in soil, romping, looking for bugs and cavorting, they become bored and stressed. When bored, these pigs gnaw and bite each other, especially tails. Being sore and tender, the pain is more intense and the assaulted pigs quickly move away rather than tolerating the aggressive biting” (20-1).

If pigs were allowed to be pigs, free to express the glory of their pigness, there would be no need to keep them in constant pain.

On Salatin’s farm, “pigs are not just tenderloin and ribs; they are co-laborers in our land-healing ministry.” They “build compost. When we feed hay to the cows in the winter, we bed the cows with wood chips, straw, peanut hulls, or any other kind of carbon we can find. . . . When the cows go back out to graze fresh grass in the spring, we put pigs in those vacated feeding areas and the pigs seek out the fermented corn imbedded in the carbonaceous diaper.” They become “pigaerators” as the “aerate the bedding and rotovate it” (22-3).

Some might conclude that we shouldn’t eat pigs, any more than we would eat hired laborers. Salatin responds by citing biblical evidence for a meat diet, and elaborates by talking about the centrality of sacrifice: “Life requires death. . . . Life is so precious that it requires death” (26-7).

But an animal can die sacrificially, die to give life to us, only if it has lived: “what makes the sacrifice of any being sacred is how it was honored in life. . . . only when we’ve honored the life do we have the right to make the sacrifice. . . . Food is life; food must live in order to die” (28).

We don’t, Salatin argues, allow our food to live – not live in the way it is designed to live, not live according to its glory. He ventures that “we’re the first culture in the world that routinely eats things that have never lived” (29).

Thus the glory of the pig: “God, in His infinite plan, offers me the distinct privilege to participate in His object lesson that illustrates God’s ultimate lifeness – caretaking and then eating enjoyably things that once lived, and now offer me life” (31).