“One of the factors that has rendered [Bach’s] Matthew Passion so successful over the course of its reception,” writes John Butt (Bach’s Dialogue with Modernity, 36), “lies in its evocation of subjectivities that somehow resonate with those of the broader modern condition.”

Bach’s Passions target “the individual believer, cultivating one’s sense of sinful responsibility for the fate of Christ, and also rehearsing essential elements of religious practice. These might involve the development of a feeling of utmost dependence, a sense of the connection between Christ’s Passion and the flawed individual’s salvation and, above all, the need for the urgent regeneration of the individual’s faith” (36-7).

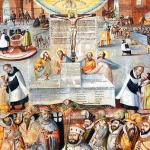

Thus, “The Passions bring to the forefront that specifically ‘modern’ aspect of subjectivity that Luther’s Reformation itself helped to inaugurate: the individual’s responsibility to cultivate faith internally as the means towards salvation, without the external apparatus of traditional sacramental practice” (37).

Bach’s achieves this in part by his adaptation of the operatic aria, sung not by a character in a historical drama but by a singer “who belongs very much to our world.” The singer of the aria is “a personage who relates to the listener ‘off stage’ rather than to the historical characters ‘on stage.’ . . . The subjectivity projected in the arias is all the more striking for its contrast with the world of the narrative, drawing in the audience as actively implicated characters in their own right” (37).

There is something to this, but it misses a couple of crucial things. First, the Lutheran reformation didn’t encourage individuals to “cultivate faith internally” without “the eternal apparatus of traditional sacramental practice.” By Luther’s lights, there was far too much attention to individual interiority in late medieval piety. The Reformation called people out of themselves.

Perhaps by Bach’s day Pietism had weakened Lutheran sacramental and liturgical piety. That leads to the second point: As Markus Rathey points out (Bach’s Major Vocal Works), Bach’s work was typically performed in a liturgical setting – surrounded by congregational hymns and bisected by a lengthy sermon. Perhaps Bach focuses on the individual, but he does so in the setting of congregational worship.

Butt knows this (p. 103), but he doesn’t seem to quite grasp the consequences: His treatment of Bach’s “modernity” depends, in part at least, on placing Bach’s work in a “modern” setting that was quite foreign to Bach.