In a wide-ranging essay on how theology alone saves metaphysics, John Milbank explores the parallels between notions of “given” and the primacy of possibility on the one hand, and notions of the “gift” and the primacy of actuality on the other.

He starts with Aristotle, for whom “the actual was primary in terms of definition, time and substance. We can define things because we encounter them; some things are possible only because other things are already actual; things that are actual are more real than things that are merely possible; ideas cannot of themselves give rise to things and finally the possible is defined by its tendency to the realisation of an actual telos.”

Aquinas takes up this perspective into Christian theology. Because the world depends for its existence on a Creator, even the necessities of the natural world are, more fundamentally, contingent: “the contingency of the created world in terms of the dependency of its partial actualisation (and so its partial perfection) upon the divine simple and infinite actuality. In this manner the relative ‘necessities’ of the created order are just as contingent as its apparently more accidental or aleatory features.”

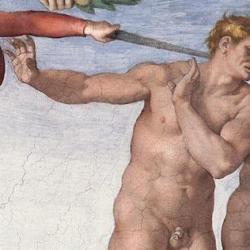

The actuality of the Creator precedes any created possibilities, and all created actualities fulfill “a divinely intended good.” Milbank sees a different perspective in Scotus, for whom “the contingency of a finite actual moment is only guaranteed by the persistence in some sense of the real possibility that things might equally have been otherwise.”

For Thomas, created actuality is “a rising order of perfections, and the complete ‘nature’ of a thing is fully determined, not by the arriving ‘gift’ of the event of actuality, but by preceding possibility.” Scotus, making possibility primary, makes a fixed essence prior to any actual thing. Actualities aren’t “gifts” realized in the giving-and-receiving; they are instantiations of essences, “givens.”

Milbank thinks that Scotus is behind modern philosophy, which gives priority to logic, will, and choice, which all express possibilities as opposed to actualities. Kant is in this tradition, in placing giving priority to knowledge over being, since knowledge has access to possibilities.

Metaphysics thus operates with a “doubly arid mere givenness,” a “cold” given: Things are given “once as possibility, secondly as existentiality and not in warm terms as the receiving of a gift – such that only the arriving actuality of a thing fully defines it as what it is: actuality fully realising formal essence.”

Milbank contrasts the post-Scotist metaphysical analysis of a bicycle with the response that arises from a “religious mind.” In the first scheme, “within the bounds of existence, a bicycle in a shop-window might present to the spectator the possibility of a gift to be given, whereas its later handing over to a child (after purchase) is the actuality of donation. At first the potential gift is just a ‘given’ in the window, while it’s later becoming a gift is a second ‘given’ fact of actualisation.”

By contrast, “the religious mind tends to read existence as such as only definable in terms of gift – as if the bicycle had never first appeared in the window and never had to be bought, but was miraculously conjured up only in that instance when it first appeared to the child on the morning of his birthday. And as if we could only receive and ride bicycles which were presents.”

Possibilism, which underwrites the given over the gift, cannot be sustained. Milbank poses the crucial question: “with the possibilist we can ask (as he does not realise), but what is the actuality of your pre-given range of possibilities?” In reality, these can only be possibilities abstracted from the actual world. To sustain a consistent possibilism, “one would have to argue, in a nihilistic fashion, that the possibilities which we can glean are only the faintest degree of the actuality of this world, which itself only instantiates possibilities from a further range of hidden and to us radically counter-intuitive ones.”

Possibilists can retreat into describing possibilities as “fictions”: “fictions, especially novels, rather show us that thickly-imagined alternative possibilities possess some degree of actuality of their own, because one can only grasp, say, the ‘logic’ of Bleak House by treating its world as a complex actuality and not at all as a mixture of essential possibilities blended together in varying combinations with certain diverting but inessential variations.”

The appeal to “fiction” actually leads us back to Thomistic creationism, the “contingency” of created necessities. Chesterton hit on this point when he argued that “the ‘other realities’ of fictions, especially fairy-tales, revealed by indirection the ‘magical’ and unfathomable curious necessities (‘limitations’) of our own world, which are inseparable from its actuality, yet which can now, through this indirection, be seen as more than arbitrary, but rather strangely necessary for the achievement of a life that bears aesthetic weight and moral solemnity.”