In Part 1 of this review, I discussed the background for David Bentley Hart’s arguments in Tradition and Apocalypse, focusing on the issues he raises concerning the diversity of early Christianity and the discontinuity of fourth-century Trinitarian orthodoxy with much that had gone before. In this post, I’m going to continue the story by looking at the work of John Henry Newman. I’d intended to discuss Hart’s critique of Newman but my interest in the broader issues surrounding Newman caused this post to balloon out of proportion. This looks like it may be a fairly long series, I’m afraid.

The Reformation and the problem of tradition

According to Hart, Newman was really the first person to pay sustained attention to tradition as a theological subject. Arguably that’s one of Hart’s overstatements. (Owen Chadwick has written a book outlining the prehistory of the concept of development between Bossuet and Newman, so I think there’s more to the story than Hart claims.) But Newman certainly provided the classic Catholic response to the challenges posed by modern historical scholarship, as Hart points out.

My own primary field of expertise is the Reformation, so for me the story begins there. That is to say, the Protestant Reformation forced Catholics to think more carefully about what they meant by appealing to tradition. Protestantism arose in part from Renaissance humanism, which asked more careful questions about the provenance and original meaning of texts than previous intellectual movements had done. European intellectuals became more sensitive than they had previously been to the differences of outlook that characterized different periods, and to the stylistic and thematic qualities that marked particular authors or particular eras.

Ancients vs. moderns

In terms of religion, this led to a growing awareness of just how different the religious world of the sixteenth century was from that of the first or even the fourth. Renaissance scholars sought to recover the original purpose, the scopus, of an author. And many of them tended to disparage what they called the “moderni,” the authors of the later Middle Ages, over against the “antiqui,” the classic authors whether of pagan or Christian literature. The ultimate “antiqui” in theology were, of course, the authors of Scripture. This preference for ancient sources combined with the scholastic understanding of intellectual inquiry as commentary on an ultimate, authoritative text to create what later Protestants would call the doctrine of “sola scriptura.”

Since only Scripture was divinely inspired, ultimately what mattered in theology was conformity to Scripture. Yet Protestant theologians were quite successful in exploiting the obvious differences between patristic and later medieval theology to make the case that the Fathers, too, were more on their side than on that of the “Papists.” Protestant use of the Fathers was selective, perhaps at times even dishonest. But Catholics labored under the disadvantage of having to defend the idea of a consistent, unchanging consensus of orthodox tradition. Protestants could reject certain things the Fathers said while making the most of points of agreement. Catholic apologists tended to feel that they had to explain away anything in early Christianity that didn’t fit the developed theology of early sixteenth-century Western Christendom.

The unanimous teaching of the Fathers

The Council of Trent made this burden official by proclaiming that Scripture should be interpreted according to the “unanimous teaching of the Fathers” as well as under the authority of the Magisterium. In the same document, Trent claims that the “saving truths” and “rules of conduct” revealed to the apostles have been preserved not only in Scripture but in “unwritten traditions . . . transmitted as it were from hand to hand.” This assumes that the traditions have been passed down in more or less unchanged form. And that was the position Catholic apologists between Trent and Newman believed they had to defend.

In the course of doing that, Catholics in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries recaptured the initiative in patristic scholarship from Protestants. Protestants continued to study the Fathers and to cite them in polemic, but on the whole they were more likely to be using editions of the Fathers edited by Catholics and to cite historical scholarship produced by Catholics than the other way round. And as Protestantism continued to change and divide, the Catholic claim of unity and continuity looked quite convincing in contrast.

The Bible, and the Bible only

In 1630, an Anglican theology student named William Chillingworth lost an argument with a Jesuit and as a result converted to Catholicism. After a year at the seminary in exile for English Catholics at Douai, he thought better of this decision and eventually returned to England and to the bosom of the national Church. He continued arguing with Jesuits, eventually writing a book defending Anglicanism against their arguments: The Religion of Protestants a Safe Way to Salvation. The book is known today mostly for one line: “The Bible, I say, the Bible only, is the religion of Protestants.”

In context, Chillingworth is saying that he doesn’t have to subscribe to any particular Protestant confession or agree with any of the major Protestant Reformers. No single theologian, no statement of faith, and not even a harmony of all the Protestant confessions defines Protestantism. He does not mean that no other writings matter, but that everything except the Bible is a matter of opinion on which people are free to disagree. Because of these views, he had some qualms about subscribing to the Thirty-Nine Articles. He eventually decided to do so on the grounds that he was simply agreeing not to “disturb the peace” of a church within which it was possible to find salvation.

Latitudinarianism or fundamentalism?

When Chillingworth wrote his book, William Laud was Archbishop of Canterbury. Laud’s version of Anglicanism cared very much about orthodoxy and about continuity with the early Church. Laud allowed Chillingworth’s book to be published after it was reviewed and revised by a committee of Anglican scholars of different theological persuasions. But over the next two centuries, Chillingworth’s dictum about the Bible as the only religion of Protestants would undermine the kind of conservative, patristic Protestantism Laud championed.

“The Bible only” could be taken in a “latitudinarian” direction, to allow for broad theological freedom. (This seems to have been Chillingworth’s own approach.) It could also be taken in a direction pointing toward later fundamentalism. That is to say, one could insist that one’s own theology was the only possible interpretation of the Bible and those who disagreed were really disagreeing with the Bible. But both of these approaches treated post-Biblical tradition as something fundamentally dispensable. It was nice to know, but at the end of the day it didn’t make a lot of difference. And one reason for this dismissive attitude was that Protestants were aware of just how conflicted and discontinuous the record of tradition was. In other words, a kind of historical sophistication stemming from the early days of Renaissance scholarship led to a sharp split between Scripture and tradition which then over time led Protestants to put less and less emphasis on the witness of tradition.

Protestantism and historical depth

In the Essay, Newman infamously pronounced that “to be deep in history is to cease to be a Protestant.” People have often misunderstood this to mean that anyone deep in history will convert to Catholicism in the “Roman” sense of the word. But that’s not what Newman meant. Newman said this early in the work, as a form of dismissal of the kind of Protestantism represented by Chillingworth. His point is that if you really think only Scripture matters, you will tend not to care very much about the witness of the historic tradition. You will mostly use it in a negative way to undercut other people’s claims about historic continuity. And you will wind up with a picture of Christianity that is indefensible from history.

Newman cites Edward Gibbon as an example of someone who was deep in history and ceased to be a Protestant Christian–or indeed any kind of Christian at all. Gibbon carried the historical skepticism of Chillingworth’s brand of Protestantism to the point of questioning all Christian claims. Gibbon had himself nearly converted to Catholicism in his youth, and his treatment of Christianity in Decline and Fall debunks Protestant interpretations of early Christianity. For one thing, Gibbon points out acerbically that the transition from true to false miracles posited by Protestants somehow wasn’t noticed by anyone at the time. (To be fair, John Chrysostom did say something about miracles not happening like they used to and I’ve had Protestants point this out as counter-evidence.) His interpretation of early Christianity is open to lots of criticism, of course. But he was right that it was something quite different from the genteel Protestantism of 18th-century England.

Anglicanism vs. Protestantism

Newman and his colleagues in the Oxford Movement in the 1830s created their own brand of Anglicanism which they explicitly distinguished from Protestantism. They drew of course on the “high Church” Anglicanism of Laud and the “Caroline divines” and the later non-jurors. But they went beyond their predecessors. They sought to recreate a pure Catholicism free from the corruptions of “Rome” and they rather implausibly claimed that this had been somehow the “real” teaching of Anglicanism all along.

When I put it that way, the Oxford Movement sounds very Protestant after all, in terms of methodology though not in terms of theological content. And I think it was. I think Newman eventually figured this out as well. Five years after writing the Essay and converting to Catholicism, Newman claimed in “Anglican Difficulties” that Anglo-Catholics were really just “patristico-Protestants.” But in the Essay on Development he distinguishes “Anglicanism” from Protestantism. (It’s easy to forget that he was still an Anglican while writing the Essay, though he was essentially “writing himself out” of Anglicanism as he did so.)

What was Newman responding to?

The Essay tackles the specific Anglo-Catholic claim to be faithful to the historic consensus of the early Church over against “Rome’s” more sectarian version of Catholicism. One point in Hart’s critique that I think he gets wrong is that he frames the Essay primarily as a response to the conflict between modern historical scholarship and Catholic claims of continuity, as if Newman were in communion with Rome and writing for a (Roman) Catholic audience. But he wasn’t a Roman Catholic at that point. He was an Anglican writing primarily for other Anglicans, explaining why he thought the Oxford Movement’s attempt to recover some unchanging essence of orthodoxy was doomed to fail.

That being said, I think Hart’s criticisms of Newman’s solution are largely correct. But to explain what those are will, I’m afraid, take yet another post. I’m at nearly 1800 words already!

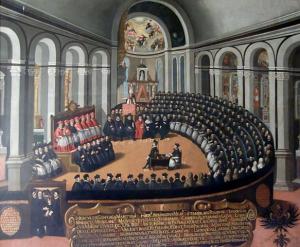

Image: Council of Trent, painting in the Museo del Palazzo del Buonconsiglio, Trento. Photograph by Laurom, used under a Creative Commons license.