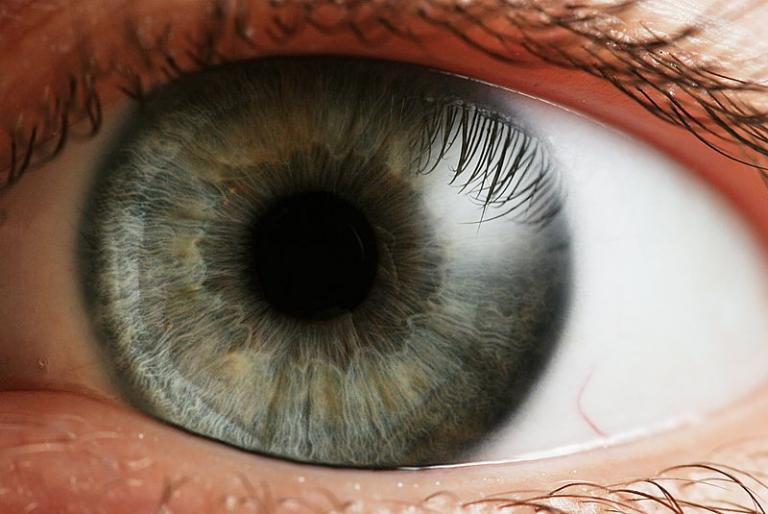

A human being is essentially an eye;

the rest is merely flesh and skin…[1]

Recently I’ve been thinking about how dependent virtue is on vision. I mean the kind of vision that Rumi hints at above – a sight that includes insight. It’s the ability, for instance, to see the repercussions of our actions for ourselves and others, both now and in the future, as well as the ability to re-vision similar experiences in the past to help guide us in the present. When we are tempted by some returning desire, fear, vanity, or anger, what often saves us is the ability to step out of the heat of the moment and expand into this greater frame of reference, taking in a wider, deeper perspective. Isn’t virtue just a great view?

It’s true that sometimes we are not able to act from this elevated perspective; sometimes our short-sighted egos just won’t let us. But when the pull of that wider vision is powerful enough, we might be able to restrain ourselves from some ultimately unsatisfying indulgence, or direct ourselves to act upon something the eye of the heart has glimpsed. So much depends on stepping out of ourselves, detached, and taking it all in: witnessing.

The twentieth century philosopher, J.W. Dunne, used an intriguing analogy to portray human perception. Here’s the gist:

An artist escapes from a lunatic asylum with a crazy ambition: he wants to paint a picture of the entire universe. So he sets up his easel in a suitable place and starts to paint. When he’s done, he stands back and sees that he has succeeded in capturing the entire universe, except for one small thing – himself. He isn’t in the picture. So he moves his easel back a little and starts on a fresh canvas. He paints the same universe, but this time shows that it is on a canvas that stands on an easel and is being painted by an artist (himself), who is standing in the very universe he is painting.

He stands back again to admire his work, but it still feels like something is missing. Then it dawns on him that the self he has painted is not his whole self, because it does not include the self who is witnessing himself witness the universe – it just shows a painter witnessing the universe. So he moves the easel back again and this time draws three universes and two painters, one witnessing and painting the other, as he witnesses and paints the universe…

Of course this goes on forever: each time the bewildered artist is dissatisfied with the picture, because there is always a greater witness over the shoulder of the one he has just painted. The analogy stirs something in my heart. The idea of witnesses stretching back into infinity can cause the rational mind to disintegrate, and something more expansive seems to awaken, a little giddy with itself. In reality there probably isn’t an endless series of witnesses within each of us (and, if there was, trying to mentally inhabit more than one or two of them would be an exhausting misadventure!). Nevertheless, it can be a useful visualisation.

A friend pointed out to me recently that the word ‘ecstasy’ derives from the Greek word ekstasis and literally means to stand outside. If we can step outside ourselves into a greater witness beyond our habitual one, do we not sense the Ultimate Witness – ash-Shahid – peering through us from the depths of infinity? Imagining those depths lined by a rank of witnesses who never make it to the Ultimate Witness because the distance is endless has a way of bringing home God’s utter transcendence. Yet it also evokes God’s immanence, for whilst the bewildered artist is stepping outside of himself, he is also journeying into the core of his own being . ‘The universe cannot contain Me,’ says the Hadith Qudsi, ‘only the heart of my faithful servant can contain Me.’

Dunne’s theory of ‘serialism’ does not end there, because by using mathematical series theory he goes on to claim that it can be logically deduced that time as a linear phenomena of past, present, and future only exists in the world of the first witness. In the worlds of the witnesses over his shoulder there would be no death and only an Eternal Present!

Serialism caused something of a stir when Dunne first proposed it in the 1930s, but it was soon dismissed and forgotten by the philosophical community. Many philosophers, being atheists or materialists, were disturbed by its mystical implications. Some claimed to have found a fault in his logic. Others, more open to the mystical, recoiled from the idea of an infinite regress, because intuitively it seems to lack a certain elegance, beauty, and simplicity.

But what does Rumi say? An endless series of witnesses is not an image he ever makes use of in his teaching, as far as I am aware. However, we do find lines such as these:

Once you get hold of selflessness,

you’ll be dragged from your ego

and freed from many traps—

come, return to the root of the root of your Self.[2]

Every stanza in the ghazal in which these lines appear finishes with the same refrain – ‘return to the root of the root of your Self’ – which might easily be transposed to ‘return to the witness of the witness of your Self’. It would be stretching it to read an infinite regression like Dunne’s in these lines of Rumi, but we can at least say that, like Dunne, Rumi beckons us to take a step back into something deeper, and both invite us on a journey towards the Self that paradoxically involves a stepping out of our selves.

And what about Rumi’s source of inspiration, the Quran? If we were asked to summarise, in a few brief words of our own, what the Quran has to tell us, ‘step back and see’ might not be a bad encapsulation. In Surah Ya Sin there are these intriguing verses stressing the importance of sight/insight:

Now had it been Our will, we could surely have deprived them of their sight, so that they would stray forever from the Way: for how could they have had insight?

And had it been Our will, We could surely have given them a different nature – rooted in their places – so that they would not be able to move forward, and could not turn back.

[36:66-67][3]

The virtuous path is aligned with perception in the first verse, whilst the second might be read as imagining what it would be like for us if we could not take a step to shift our perspective, but instead, like plants, our movement was restricted. Elsewhere, the Quran leaves us with no doubt about the importance of our self-awareness and this two-way vision:

On the earth are signs for those with inner certainty,

just as within your own selves; will you not then see?

[51:20-21][4]

Or, as Rumi puts it with some urgency:

Dissolve this whole body of yours in vision:

pass into sight, pass into sight, pass into sight![5]

Perhaps the repetition of the command ‘pass into sight’ is not simply for emphasis. Whilst it may not suggest a passing into sight from one witness to another in an infinite series, it could suggest that passing into sight is a process that requires continual movement, renewal, and repetition. Without getting caught in an unwieldy infinite regress within the individual, Rumi’s vision seems to hint at an infinite unfolding within the quality of Sight itself. The individual dissolves, only the words on his tongue remaining: Ya Shahid! Ya Basir! O Witness, O All-Seeing One!

[1] Mathnawi VI, 812, trans. by Kabir and Camille Helminski in Jewels of Remembrance.

[2] Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi: 1926, trans. by Kabir Helminski in Love is a Stranger.

[3] From Surah Ya Sin in the Quran, trans. by Camille Helminski in The Light of Dawn.

[4] From Surah a-Dhariyat in the Quran, trans by Muhammad Asad in The Message of the Quran.

[5] Mathnawi VI, 1463, trans. by Kabir and Camille Helminski in Jewels of Remembrance.