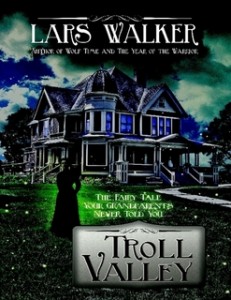

This article on “Christian fantasy” by novelist Lars Walker confesses something that may surprise his readers:

I don’t read much fantasy, and I read almost no Christian fantasy. I’ve been burned too many times. You buy a book, hoping to experience over again the joys great fantasy can provide (for me, the Mines of Moria, the Ride of the Rohirrim, and the resurrection of Aslan provided the greatest moments of joy I’ve ever experienced in literature), and what do you get? Wannabees. Wannabee Tolkiens, wannabee Lewises, wannabee (christened) George R. R. Martins.

While I might have named different storytelling moments — scenes from Watership Down, The Tale of Despereaux, Winter’s Tale, along with some from The Fellowship of the Ring — I found myself nodding in agreement.

But then I came upon this surprising paragraph…

Who’s writing good Christian fantasy today? … Walter Wangerin Jr. wrote one of the best fantasies of any kind I’ve ever read, The Book of the Dun Cow, an amazing animal story that I promise will break your heart and put it together again. Stephen Lawhead is an excellent writer who has never (in my opinion) soared to the heights he’s capable of. Jeffrey Overstreet may be the best.

Wow.

I’m honored and grateful and inspired to get back to work on my new novel. I’m grateful that Walker appreciates these books so much.

Walker’s a formidable storyteller himself. His novel Wolf Time is on my nightstand right now. (I tend to read a dozen books at a time, little by little, over many months, and this is the only fantasy novel currently in the mix.) So, to be highlighted by him is a huge encouragement, and it sends me toward a weekend of writing with new enthusiasm and confidence.

Walker’s a formidable storyteller himself. His novel Wolf Time is on my nightstand right now. (I tend to read a dozen books at a time, little by little, over many months, and this is the only fantasy novel currently in the mix.) So, to be highlighted by him is a huge encouragement, and it sends me toward a weekend of writing with new enthusiasm and confidence.

However — friends, family, and those who have been reading this blog for a while probably know what I’m about to say — for the sake of preventing misunderstanding, I am duty-bound to offer a contrary opinion. I know, it feels kind of self-defeating to disagree when somebody says something complimentary about my work, especially when that somebody is more experienced and more accomplished.

But here I go anyway…

I don’t write “Christian fantasy.”

I write fantasy.

While I do have some Christian readers, I don’t write stories for a Christian audience, nor are my stories designed to deliver “Christian messages.” There is no reason for my novels to be segregated from other novels, to be branded as part of some sub-genre.

I want my stories to be held to the standards of great fantasy writing. They may fail by that standard — only time, and greater imaginations than mine, will determine that. But “make-believe” is the game I’m playing, the tradition I’m following, the goal I’m seeking to achieve.

I wouldn’t know how to write “Christian fantasy” if I tried. I don’t know what it is. I don’t see labels for “Hindu fantasy” or “Buddhist fantasy” or or “vegetarian fantasy” or “atheist fantasy” in the bookstores, and there’s a good reason for that. Art is about exploring possibilities, not fashioning messages or proselytizing. When artists start trying to “make points” or “deliver messages,” their art suffers and becomes something else.

Much of what I’m saying has been expressed here many times before, primarily in the foundational vision of this blog: “Mystery and Message,” by Michael Demkowicz. If you haven’t read it, check it out. It says a great deal in a few words.

You’re probably familiar with author Katherine Paterson. She wrote Bridge to Terabithia and Jacob Have I Loved. In a Books and Culture interview, she once said,

Novelists write out of their deepest selves. Whatever is there in them comes out willy-nilly, and it is not a conscious act on their part. If I were to consciously say, ‘This book shall now be a Christian book,’ then the act would become conscious and not out of myself. It would either be a very peculiar thing to do–like saying, ‘I shall now be humble’–or it would be simple propaganda…

Propaganda occurs when a writer is directly trying to persuade, and in that sense, propaganda is not bad. … But persuasion is not story, and when you try to make a story out of persuasion then you’ve done something wrong to the story. You’ve violated the essence of what a story is.

I don’t have the stature of Paterson. I am not one of the great fantasy writers of the world. But that’s not something I worry about. When artists concern themselves with their own greatness, they’re in trouble. I want to focus the energy and time I’m given differently. I want to discover stories that are unfamiliar, that wrestle with questions that are new and challenging for me. I’m focused on developing characters I find interesting, so I can follow them.

And I trust that if I pay attention and work hard, they will lead me to all kinds of truth, all kinds of beauty.

My grandfather didn’t build “Christian houses” — he built spacious, sturdy, wonderful houses worth exploring. In a way, I’m doing my own work inspired by him. My stories are not “Christian stories” any more than my coffee is “Christian coffee,” and my favorite hill climbs of the Pacific Northwest are not “Christian hiking trails.” I don’t want my companions on the journey to think that we’re engaged in some kind of illustrated sermon. We’re on an adventure.

“Ah,” you might say, “but you are a Christian. Your beliefs will affect your story. So your stories will reflect truth differently than secular stories do.”

My answer to that — “No, not necessarily.” In my life of reading, moviegoing, listening to music, and studying visual art, I have encountered truth, beauty, and mystery as much in the work of non-Christians as I have in the work of Christians. I’d even go so far as to say that the truth and beauty I have found in the work of unbelievers has strengthened my faith even more than what I’ve found in “Christian art.” And that’s to be expected. I believe that we are all made in the image of God, and that eternity is written in our hearts… in all of our hearts. Thus, when anybody achieves any kind of beauty or truth in their work, that goodness is from God, whether the artist likes it or not.

I want to write stories for the whole world, stories that enchant readers with their beauty, provoke readers with their questions, haunt readers with their mysteries. I want to write stories that inspire readers to investigate important questions, rather than illustrating arguments in hopes that they’ll agree with me.

If my work is categorized as “Christian fantasy,” all kinds of trouble and misunderstanding begins. People begin to assume — wrongly — that they should be looking for religious symbolism and and allegories that I seek to avoid. They write reviews on Amazon that severely misinterpret the stories. (Many of the reviews of The Auralia Thread there, even the positive ones, make me cringe because readers have read them with only one set of lenses — lenses you use when you think that your job is to discern a religious allegory. As a result, they’ve missed out on much of what I believe these stories are about, and they ignore all kinds of details and characters and subplots that are essential to the story.)

Novels by Marilynne Robinson, Leif Enger, Katherine Paterson, Wendell Berry, Madeleine L’Engle, J.K. Rowling, Walter Wangerin Jr., Tim Powers, Gene Wolfe, and J.R.R. Tolkien are shelved in Literature or Fantasy. I’m not saying my work is as accomplished as books by those great writers — Christians, all of them — but if Auralia’s Colors, Cyndere’s Midnight, Raven’s Ladder, and The Ale Boy’s Feast are branded as “Christian fiction,” they’ll remain set apart from the books that inspired them, taken away from the audience for whom I wrote them.

Novels by Marilynne Robinson, Leif Enger, Katherine Paterson, Wendell Berry, Madeleine L’Engle, J.K. Rowling, Walter Wangerin Jr., Tim Powers, Gene Wolfe, and J.R.R. Tolkien are shelved in Literature or Fantasy. I’m not saying my work is as accomplished as books by those great writers — Christians, all of them — but if Auralia’s Colors, Cyndere’s Midnight, Raven’s Ladder, and The Ale Boy’s Feast are branded as “Christian fiction,” they’ll remain set apart from the books that inspired them, taken away from the audience for whom I wrote them.

Even if my stories pale by comparison, they were written in the same genre as books by George R. R. Martin, Neil Gaiman, Mervyn Peake, and Patricia McKillip (writers whose stories are, by the way, filled with echoes of Christ’s teachings… whether they intended that or not).

If you were a winemaker, and you found your bottles shelved with diet soda, or vice versa, you’d be bothered, wouldn’t you? If you made a sports car, and found it advertised as a family SUV, you would suspect — correctly — that its real purpose would never be discovered or acknowledged. Further, it would greatly confuse shoppers who were looking for a family SUV.

If truth and beauty and mystery — those things that make us wonder about God and salvation and the meaning of life — are what make a book “Christian,” than I’d argue that most of the best “Christian books” were not written by Christians, and you can find them all over the bookstore, not just in the “Religion” section. Finding Nemo, WALL-E, and John Carter were all stories written by the same filmmaker — who happens to be a Christian — and all three were full of ideas and themes that Christians will celebrate. But they were not “Christian movies.”

Here’s a passage of Walker’s article that made me cheer:

How do you produce good fantasy (I won’t say great fantasy; that’s beyond my expertise)?

First of all, remember this truth—e-books make it possible to publish your own book. That does not earn you the right to expect anyone else to read it.

Writing is a craft, like shoemaking. I don’t care how sincerely the guy who made my shoes loves shoes. The main thing I want from him is expertise, the practiced knowledge of how to put together a shoe that fits, won’t give me blisters, and lasts a while. Your sincerity may please God, but He also says, “Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for men” (Colossians 3:23, NIV). It’s possible you may be a prodigy, a literary Mozart capable of amazing the world right out of the gate. But probably not.

Amen to that!

That’s why I buy the best shoes I can buy. And I have never, ever, ever shopped for “Christian shoes.”

That is why you should check out Lars Walker’s fantasy novels. They are heavy, challenging fantasy stories that fans of the Inklings — and beyond — will find rewarding.

That is why you should check out Lars Walker’s fantasy novels. They are heavy, challenging fantasy stories that fans of the Inklings — and beyond — will find rewarding.

So again, sure, it’s encouraging that someone familiar with “Christian fantasy” — whatever that is — would say that he likes my work. Especially an accomplished writer like Lars Walker. But to be honest, I’m hoping that somebody somewhere will someday read them the way they read any other fairy tales or fantasy novels, find something that troubles or intrigues or haunts them, and tell their friends, “I just read the strangest fantasy series.” To deliver that — instead of something called “great Christian fiction” (as nice as that might sound) — would feel like a mission accomplished.