My last post was about rising seas (Noah and the Flood). The next one will be about technology’s dangers (the Tower of Babel). Both of them put me in mind of the theme for today’s break from the “Rowing through the Old Testament” series.

My last post was about rising seas (Noah and the Flood). The next one will be about technology’s dangers (the Tower of Babel). Both of them put me in mind of the theme for today’s break from the “Rowing through the Old Testament” series.

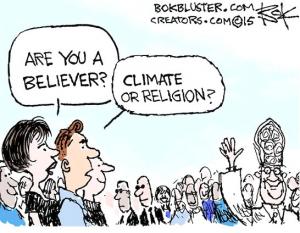

Climate change is real, caused by human activity, and a serious threat. That’s the majority opinion in the world today. Many conservatives, including religious conservatives, don’t but it. This post explores my puzzlement about the connection between conservatism and climate-change denial.

Religious voices encouraging action on climate change are being heard in greater numbers and with greater frequency. (See here (the Vatican), here (some 20 Protestant leaders), and here (500 religious leaders and scientists of Massachusetts). It’s time to address a phenomenon that has me puzzled. Why are so many conservatives, especially religious conservatives, taking a wait-and-see or even a denial position on climate change? In this post I address just such a conservative with what, to me, seems to be entirely conservative reasoning.

Can the fading, but still significant, connection between climate change denial and conservatism generally or conservative religion in particular be broken completely. Perhaps not for one friend, who has been pastor of the local Assembly of God Church. He holds that the Bible is inerrant in every respect. He’s a “young-earth creationist.” He believes the universe was created about 6000 years ago. That rules out the theory of evolution, which is at the heart of modern science. For him doubting science’s conclusions about climate is easy, especially since some of the evidence for climate change comes from studies of how the climate has changed over much more than 6000 years.

Most conservative Christians are not young earth creationists. Still there is a marked correlation between conservative Christianity and climate change denial. (But check out this online article,” where Brian McCammack sees much more diversity among rank and file Evangelicals than their leadership would indicate.) And that’s strange. How strange I hope to show by looking at the conservative temperament and applying what I see to climate change.

Here’s an unscientific, but I think fair, list of conservative attitudes:

- A preference for stability. Change is OK if it’s gradual and well thought out.

- A belief in truth, even absolute truth, and our ability to know the truth.

- An inclination to accept authority. This doesn’t exclude questioning, and it doesn’t have to mean submissiveness.

- A style of living that emphasizes prudence as opposed to risk taking.

- In this country a commitment to capitalism with minimal government interference and a high regard for individual freedom, especially concerning property rights.

- A sense that responsibility for others starts close to home.

Taken together these attitudes should support a person’s acceptance of the science on climate change. Let’s look at them more closely.

- Preference for stability. Climate change is quite possibly the most destabilizing factor in the world today. Of course, this matters not at all if climate change isn’t real, so we go on.

- Belief in truth and our ability to know it. A conservative person is the last one to say, “You have your truth and I have mine.” The facts about climate change are public and publicly available. But disagreements to arise, so where does a conservative turn?

- Acceptance of authority. I’m assuming a conservative who is not the world’s foremost expert on climate. An authoritative source is important for that person—and for me. Not everyone’s opinion is equal for a conservative. A conservative listens to the best informed opinions. When that’s hard to determine, a conservative follows the majority opinion among authorities as at least more probably right, recognizing that it could be wrong.

Here the real strangeness with conservatives and climate change comes out. The scientific authorities are in almost unanimous agreement. There are near unanimous agreements among other authorities as well. World governments have all signed on to the Paris Climate Agreement with only one major exception and that only since last year. Religions, have largely sided with the governments and the scientists. These include Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and most of Christianity. The last three popes and the American Catholic bishops as well as bishops worldwide; the World Council of Churches and most Protestant denominations including the theologically conservative Southern Baptists; the Eastern Orthodox Churches—all of these have statements supporting the theory of climate change and calling for action. Even the oil companies officially accept the science of climate change, though their actions speak louder than their intra-company e-mails. And insurance companies are worrying about big payouts due to climate change. If authority means anything to a conservative, this amount of authority ought to be enough.

- The virtue of prudence. Still there’s no denying that authority can be wrong, even when it’s unanimous. The American Catholic bishops, as far back as the 1970’s, had the correct conservative advice at a time when climate science was in its infancy. The bishops appealed to the conservative virtue of prudence. The probabilities of the worst effects of climate change were not clear then, but the danger was great enough that the bishops said it was morally necessary to be prudent, to act even without certain knowledge. As everyone knows, we did not act. We were not conservative enough, and now it’s very late.

- Capitalism. What passes for a conservative view on the American economy is capitalism in a substantially unguided form. This economy is responsible for the most rapid and radical changes a society has ever seen. It’s been anything but gradual and well thought out. For truth, which ought to be susceptible to evidence, we’ve substituted a number of myths: More is better; progress is inevitable; wealth trickles down, an “invisible hand” guides individual selfish decisions, and “We’re just satisfying customer demand.” No authority can tell such an economy what to do, regardless of social or environmental harm that may accrue. Prudence, especially in the form of thrift, is the enemy to that economy’s most efficient functioning. This is a much too profligate “conservatism,” and easily recognizable as a major contributor to climate change.

- Responsibility. Two important concepts in Catholic social justice are subsidiarity and solidarity. Subsidiarity means dealing with problems at the smallest, most local level possible. That goes nicely with the conservative sense that responsibility for others starts close to home. If there’s any problem that does not fit well into that scheme, it’s global warming. Solidarity extends the reach of our concern to larger communities and the entire world. Solidarity means we act not only as individuals but also as communities, nations, and even, when necessary, the worldwide community of nations. We navigate between subsidiarity and solidarity by a traditional principle that I think conservatives and liberals can accept: Virtue stands in the middle, or the Golden Mean. One can’t go all out with either subsidiarity or solidarity. There are times when local action is required, and there are times when governments and even international institutions need to act. Prudence and an eye for what’s real and true help us know the difference. Neither of those qualities is especially liberal.

Conclusion: Climate change and conservatism are a natural fit. If anybody ought to be on board with climate change, it’s a conservative.

Image credit: Science Matters, WordPress.com