Jesus fully human is more central to Christian belief than Jesus the miracle worker. We have this image of Jesus walking on water and we use that image conversationally for people who think way too much of themselves – “She thinks she can walk on water.” But that’s a criticism; it’s not a proper way for a person to think. Is it proper for Jesus and not for us? Did Jesus think he could “walk on water,” work a miracle anytime he wanted?

I have to admit to having a distaste for that image of Jesus. It seems to make Jesus both more and less than, but not really, human. In my last post a generic, but realistic, atheist asks, ”Why didn’t Jesus cure everyone in Palestine?” The answer I would like to give, based on my personal bias, is: Because he couldn’t. But personal biases are exactly what a person ought to distrust.

Bible scholars have done much critical analysis of the biblical traditions that give us Jesus as miracle worker. This post takes a look at that research and concludes Jesus really did work miracles. Squaring that historical probability with a fully human Jesus is a task for the future.

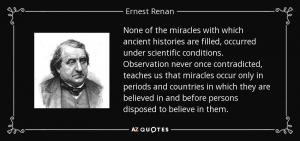

Early scientific bias in Jesus research

Early searchers for the historical Jesus generally did not like to think of Jesus as a miracle worker. They tried to show that the miracle stories in the Bible do not go back to Jesus himself but arose later as legends and stories told by overly enthusiastic followers. These 18th and 19th century scholars had absorbed the scientific tenor of their age. They were biased against anything supernatural interrupting the natural flow of things (like me, I confess).

Later, more controlled scholarship revealed the uncomfortable truth: Miracle stories go back as far as we can detect in the development of the early Church’s writings and oral traditions about Jesus. Most scholars, whether believers or not, don’t accept every miracle story in the gospels at face value, but they do say Jesus had the reputation of miracle worker even during his lifetime, and they say that reputation must have had some basis in fact. (Walter Kasper, Jesus the Christ, p. 90-91)

How did those early scholars imagine they could slice out all the miracle stories from the gospels, as if they were just later lore added to an original gospel? How do later scholars say something like that, but only about some of the miracle stories? Answering that requires a look at …

Layers of traditions about Jesus.

When you look at a book published today, the first bits of information you see are the book’s title and author. Turn a page and you can usually find the publication date. This information is missing from the books we call the gospels. There is a title, which scholars think was added later: “The Gospel of Jesus Christ.” We’re never told the author or the date of composition. The names that we have for the Gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are later guesses and probably wrong.

Date and authorship are things that scholars would really like to know. It would be very helpful for assessing the historical accuracy of the material contained in a book if we knew how close to the actual events and from what possibly biased perspective the author wrote.

The priority of Mark and the hypothetical Q

Very early in modern historical Jesus research, scholars found a way to tell the order in which the various gospels were composed. They noticed that the first three gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, are very similar. They called these gospels “synoptic” (syn=together, optein=see). You can line these gospels up side by side and see the same story–with some changes, additions, and deletions–unfolding in each one. Then scholars noticed that nearly all of Mark is present in Matthew and Luke and in the same order. They concluded that somebody copied from somebody. The near universal opinion among these scholars today is that Mark was first and Matthew and Luke followed.

Looking at Matthew and Luke, you can see they have a great deal of material in common that was not in Mark. This consists largely of sayings of Jesus. Matthew and Luke could have had another source in common, which scholars call the “Sayings Gospel” or “Q.” Q is the first letter of the German word for source. No copy of Q has ever turned up. It remains a hypothesis, but a widely held one. A minority theory is that the author of Luke may have known the gospel of Matthew. That would make Q unnecessary as an explanation for the material they have in common outside of Mark.

In addition to Mark and a possible Q, Matthew and Luke each had their own unique material, either written or oral, which they added to Jesus’ story.

Miracles in very early traditions

Here’s the majority opinion on the order of various sources with some commonly attributed dates:

- First were seven authentic letters of Paul, all probably composed in the decade of the 50’s. Six other letters attributed to Paul are thought to be later compositions by disciples of Paul.

- Then came Mark, around the year 70.

- Then Matthew and Luke in the decade of the 80’s.

- Finally John in the 90’s.

- The Q document, if it existed, it must have been pretty early but not necessarily earlier than Paul.

- The special materials used by Matthew and Luke could have been fairly early as well.

- All of these sources rely on earlier written or oral traditions, and sometimes these can be identified, for example, when Paul quotes a hymn that was being sung in his local churches.

I count five or six “original,” i.e., not copied, sources for the story of Jesus: Paul, Mark, Q (if it existed), Matthew’s special material, Luke’s special material, and John. Paul and Q have little to say about the deeds (as opposed to the words) of Jesus during his earthly lifetime. All the rest contain accounts of miracles. Even Q has a saying of Jesus that refers to miracles.

The upshot is that scholars cannot find an original “layer” of information about Jesus that does not contain miraculous deeds. Historians don’t like to attribute impossible deeds to any historical person, but one conclusion is nearly inescapable: Whatever Jesus thought of himself, people who knew Jesus thought he was a miracle worker.

It seems we need to accept both the miracles and the humanity of Jesus. Our reality is that we can‘t work miracles. In what way is Jesus’ reality like ours? Future posts put the humanity of Jesus front and center. We can’t cure anyone we might want to. That’s just reality for us; the science is settled. Is it Jesus’ reality as well?