When scribes and Pharisees brought to Jesus a woman “caught in the very act of adultery,” Jesus wrote on the ground. What was he writing? People have used their imaginations to fill in this missing part of the story. I will do that too, but my imagination goes in a different direction from the usual, i.e., a list of the woman’s accusers’ sins. I would have Jesus witnessing for the woman instead of against her accusers.

This is the 15th in the series “Stories of Jesus and the Character of God.” We’re looking at episodes of Jesus’ journey from Temptation to Cross. The whole series aims to find in Jesus clues to what God is like. Developing Table of Contents for the series here.

Imagining what Jesus wrote

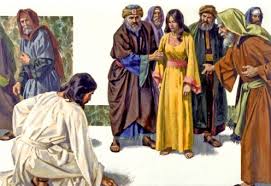

The scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman [to Jesus] .… They said to him, “Teacher, this woman was caught in the very act of committing adultery. Now in the law Moses commanded us to stone such women. Now what do you say?” … Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. When they kept on questioning him, he straightened up and said to them, “Let anyone among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her. And once again he bent down and wrote on the ground. (John 8:1-11)

What was Jesus writing on the ground? People have imagined that he was embarrassing the woman’s accusers by writing their sins. That makes a good addition to the story, but I want to vary it a bit.

The first thing to say is that this story comes from the Gospel of John. Of all the gospels this is the most theological and the farthest removed from Jesus’ actual history. So if we’re wondering what Jesus might have written on the ground, we really have to be thinking of Jesus as a character in John’s book. John may have been working with an actual memory of scribes and Pharisees confronting Jesus as in the story, but still it’s a story. Speculating about what Jesus might have written requires us to look into John’s mind.

Sexual mores in the ancient Roman world

By John’s time Christians had 60 years to try to make their way in the world. That world had a significantly different view of sexual morality and adultery than their own, largely inherited from the Jews. We have had much longer than that to misunderstand what those early Christians were up against. The part that we tend to miss is the most obvious thing for anyone in the first-century Mediterranean world—slavery and class distinctions.

Greeks and Romans weren’t as sexually uninhibited as is sometimes portrayed. They considered sex between a married person and someone other than that person’s spouse as, if not sinful, at least uncouth; but they made exceptions for slaves, children, and prostitutes. According to Kyle Harper (in From Shame to Sin: The Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity),

What mattered, in Roman law and in Roman sexual morality, had little to do with sex. It had everything to do with whose bodies could be enjoyed with impunity and whose could not be touched without elaborate formulas of consent. (Quoted by one of my favorite bloggers, Artur Rosman in “Cosmos the in Lost,” April 17, 2015, . I’m relying on his review of Harper’s book for this section.)

What set Christian sexual morality apart was not that it was stricter when it was in force but that it was always in force. There were no exceptions. All people had intrinsic value that had to be respected. That includes the victims of a society that clings to its own righteousness.

The prostitute

The scribes and Pharisees in the story bring the woman caught in adultery to Jesus while he is teaching in the temple area. How convenient that they should happen upon this woman at just the right time! Or else they planned the confrontation in advance. Their problem was only knowing when or where to find Jesus. Having found him, the next part was easy. They could find a suitable woman any time in a house of prostitution. The story doesn’t say so, but I’m guessing the woman would have been a prostitute.

If we look through John’s eyes, we can get a different idea of what Jesus was writing on the ground. John’s Jesus may have compared not their sins to hers but her nobility to their self-righteousness. In John’s view a prostitute isn’t one you can “enjoy with impunity” but one whose rights are being regularly violated. That starts with the conditions which often forced widows or unmarried women into a life of prostitution in the first place. She was not a sinner so much as a victim of society’s sin.

John’s Jesus doesn’t approve of prostitution. That’s obvious from his concluding words to the woman, “Go, and from now on do not sin anymore.” I often wondered how this woman would have managed to obey this directive and what help Jesus or his followers would have provided her.

In the community of disciples

Christians with too much imagination thought the woman was Mary Magdalene. Turning from her “evil” ways, she followed Jesus, and was rewarded with the first vision of the risen Jesus. But the Bible says nothing about Mary Magdalene as a prostitute. In fact, she was a woman of considerable means—not the prostitute type. She accompanied and supported Jesus’ band of apostles. Some today consider her one of the apostles.

The woman of the story couldn’t have been Mary from Magdala. But I imagine one or more women caught in the very act of adultery may have joined the disciples either while Jesus was still with them or after. Certainly such a woman would find help to start a new life in one of the new Christian communities. About these communities Luke writes:

All who believed were together and had all things in common; they would sell their property and possessions and divide them among all according to each one’s need. (Acts 2: 44-45)

The God of Jesus is not only the God of individuals, enforcing a personal morality and outlawing our individual sins. God is the God of the powers under which, the conditions in which we make our way in this world. Those powers and conditions need reforming as much as any individuals. When the woman’s accusers walked away, it mightn’t have been their personal sins that embarrassed them, but it might have been sins after all. Scribes and Pharisees were among the beneficiaries and upholders of the system that kept many in poverty. That would have included the woman whom Jesus saved from stoning.

Image credit: Orthocuban via Google Images