Celebrations of Grace: The Sacraments of the Catholic Church, Part 14

We often think about the Sacrament of Reconciliation—or any occasion when reconciliation might be in order—backwards. We think: First, the person who committed the offense shows some evidence of sorrow. Then the injured party forgives and reconciliation can occur. Actually, it works much better the other way around. It’s easier to be sorry when you know you’ve been forgiven already.

The many sayings of Jesus on this subject are at least as much about forgiving as they are about going to someone to say, “Sorry.” The Lord’s Prayer is about forgiving and receiving forgiveness equally. The Prodigal Son doesn’t expect forgiveness, just a slave’s job; but he finds a father who has forgiven him already and is waiting and watching for the sinner’s return.

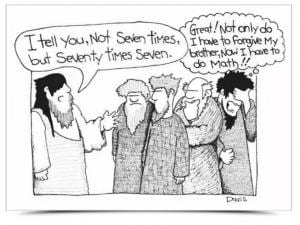

In a third saying Jesus tells Peter to forgive his brother seventy times seven times. This is not an exaggeration. You can expect to have to forgive a family member easily that many times. But what if you were to say each time, “I’ll forgive you, but first you must be truly sorry, pay restitution, and promise not to do it again”? I don’t think either forgiveness or repentance could happen that way—at least, not 490 times.

Real power from the Spirit

Then there’s the passage in which the Church finds much of its theology of the Sacrament of Reconciliation: ”Receive the Holy Spirit. Whose sins you forgive are forgiven them. Whose sins you retain are retained.” (John 20:22-23) Here’s an interpretation: ”The Holy Spirit is giving you real power. Accept it. If you forgive your sons and daughters, your spouses, your brothers, sisters, friends, even enemies, then forgiveness happens. But if you withhold your forgiveness or carry on politely but hold a grudge in your heart, how are they going to find sorrow in their hearts? If you say, ‘I will forgive you but only provided such and such or so and so,’ you treat them as inferiors. Where will they find the will to approach someone who seems to be assuming the role of the guiltless one? And who can they get forgiveness from if not from you, the one that matters?”

Forgiveness is one of the most important skills we can have. It’s also one of the most difficult, but without true forgiveness true sorrow is next to impossible.

Forgiveness first

I used to think that Jesus died such a horrible death on the cross so the world would see how bad its sin is. Then we’d somehow find the humility to approach God for forgiveness. Now I believe that it’s only through being forgiven (“Father, forgive them, they know not what they do.”—Luke 23:34) that we can acquire the courage to see our sin and how terrible it is.

The hardest part about the skill of forgiveness is that it’s not something we do. It’s not giving advice, blaming, giving orders or suggestions, threatening, preaching, giving logical arguments, making judgments, explaining, or even making excuses for the other. We’re tempted to begin right away trying to fix whatever we imagine is wrong inside the other person. That person needs to respond to the truth—what really happened and how it hurts—not our righteous anger and our threats and conditions, but also not our attempts to make things better, not our condescension, not our attempts at being strong and hiding the hurt, and not even our willingness to forget.

All these are actions of a superior toward an inferior, punishments or favors bestowed freely or with strings attached. Forgiveness is not seeing justice done or doing someone a favor. Can you possibly think of what the Loving Father did to the Prodigal Son as a favor? The Father was just being a father. To be true to ourselves, we have to forgive. And we have to forgive in order to find healing ourselves–healing of our own inevitable emotions of anger, resentment, and that hidden fear that we are not as innocent as we like to think we are. Reconciliation is a sacrament of healing on many sides.

Reconciliation, God’s work

God’s grace often makes our actions into instruments of divine power, but with the grace of reconciling, the action is almost all God’s. It’s hard to let God do so much! You want to do something to make reconciliation happen; yet often the only thing that doesn’t make things worse is to wait and worry and continue in love. It’s a strange kind of skill, letting another person feel sorrow, giving a person a chance and time to be sorry. You can’t help much. You can examine yourself and be honest about your own role in the conflict, and you can allow time for a gradual clearing of vision.

Unpressured, unhurried time makes sorrow possible. You must protect yourself physically and emotionally. I’ve seen parents try their hardest to continue loving wayward children even while trying to maintain an emotional and physical distance, and I’m convinced God’s forgiveness was touching those children. That’s what “Receive the Holy Spirit. Whose sins you shall forgive….” is about.

The grace of forgiveness and contrition is real. Against all odds and almost against human nature, reconciliation does happen. We do make up, make amends and make changes, even if it’s not always for the best reasons and even if it sometimes seems more like ignoring the problem than working it out. The Sacrament of Reconciliation celebrates this fact of our tarnished but still wonderful lives.

A community sacrament

Reconciliation includes our reconciliation with God and with each other. The community dimension in this sacrament was not very obvious when going to Confession was always a private ceremony. We believed, and still do believe, that the priest represents Christ and the community in which one seeks reconciliation. But this connection to community is stronger when on regular occasions the peace-seeking community, the community that forgives and asks for forgiveness, gathers to celebrate, and when a reading from the community’s story, Sacred Scripture, is a prominent part of the celebration.

The two sides of reconciliation, forgiving and being forgiven, are especially obvious if the ceremony includes a sign of peace. As in the other sacraments, the gathering of sinners is an important sign. It’s the first of the signs in which God is present.

The battle with sin

Some say there are no mistakes, only different roads to the goal. Mistakes are just “learning experiences.” Christians believe the part about the different roads, but they also believe in turning away from sin. Christians believe in mistakes and in conversion. They believe in forgiveness, and so they have the courage to acknowledge the sin that is forgiven. They believe in a savior, whom they will find waiting down every road.

The sacrament of Reconciliation is about struggling with sin, that age-old battle with the devil. We cannot think, “I’m going to win this fight.” Jesus already won it. But our struggle isn’t any less intense or any less a part of God’s plan for transforming us into the people we were meant to be. It simply fills the struggle with hope.

God brings good out of everything, including our sin. Through the grace of humility we can realize that. We can even think back on our past sins and thank God for another time of special closeness and love. That’s what the Church does during the Easter Vigil. We think back on the story of the first sin and sing in the Easter Proclamation: “O happy fault!”

In the celebration of Reconciliation, we say words and perform gestures that express our sorrow for offending our loving God. The real sacramental sign, however, is not these outward things. The sorrow that we feel inside and other feelings, too, including our confidence in God’s mercy and the peace and joy that reconciliation brings, are the real sign of what Christ is doing in our lives—forgiving us, giving us the grace of contrition, fashioning us into people who forgive seventy times seven, and reconciling us to each other and to God.

Think again:

In times of temptation, especially when we are tempted to be unforgiving, our battle against sin and the devil becomes real. In Reconciliation we think about forgiving and being forgiven, and we celebrate. What kind of battle is it if celebrating forgiveness is one of the necessary strategies? What does it take to be sorry or forgiving?

Image credit Phillip Chircop via Google Images