The first of the two main parts of the Mass is a sharing of God’s word of salvation. We sit to listen to the Word of God except that we stand for the Gospel. That ought to tell us that there is more than listening going on in the Liturgy of the Word.

This post on the Liturgy of the Word is the second in a series that will take a look at the way the Mass is celebrated in Catholic churches today.

Before the renewal of the Church’s liturgy, the Mass contained an Epistle and a Gospel. Today the Liturgy of the Word (a phrase we didn’t hear before) contains three readings plus a psalm. Before, the same Scripture passages were repeated every year. Now there is a 3-year Sunday cycle and a 2-year weekday cycle. But the difference goes beyond quantity of Scripture that we get to hear.

Active listening in the Liturgy of the word

Once Catholics were taught that they might come late to Sunday Mass, for a good reason presumably, miss the first part up to the sermon, and still have made their Sunday Mass obligation. Today it makes no more sense to miss the Liturgy of the Word than the Communion Rite.

The Liturgy of the Word is Jesus speaking to us, but it is more than getting a message, even one that comes from Jesus. The imaginary space visitor that I introduced in previous posts knows how things used to be. The priest read in Latin and people following with translations in books. They got the message well enough. But the Liturgy of the Word is not a Bible lesson, in Latin or English. The first clue that this is so is the work of the lector.

Storytelling isn’t just telling a story. When folks get together and stories get told, the listeners as well as the speaker are involved in the telling. They respond with appropriate noises and gestures. Most of all, there is a rapport between speaker and listeners. In church lectors try to accomplish this by making eye contact. It’s hard to do when people have their eyes focused on the pages of a book. In many parishes that’s a habit left over from the days of the Latin Mass—amusing to my extraterrestrial friend but frustrating to the lector.

It also frustrates an important purpose, namely, to celebrate God’s word. The celebration is a sharing of a story, not studying to make sure you don’t miss something. Some parishes make a small supply of books with Mass readings available for those who want them but books in the pews contain only songs and people’s responses. I like that way of encouraging people to listen.

Our stories

Why does the way we get the message matter as long as it’s the same message? Why did the Liturgy of the Word have to change from Latin to English?

Hearing somebody tell a story draws us closer in than reading it from a book, but this obvious reason doesn’t go far enough. The fact is we are already part of the story even before we hear it. These are our stories so they ought to be in our language. God’s Word lives in God’s people first. After that it is words that we read and a message that we hear. At the Liturgy of the Word we don’t just hear a message; we celebrate our story in our words. And the words that come closest to our hearts are words that we hear spoken.

The Liturgy of the Eucharist doesn’t stand on its own very well. It needs the Word to help establish its meaning. That Word, which we get from the Bible, is about ordinary people with ordinary needs, ordinary faults and strengths, successes and tragedies—a lot like us and the things that go on in our lives—and how God works through all of them. If we go beyond the literal meaning of the Bible stories to its “spiritual” sense, we find that the Bible isn’t just about people like us; it’s about us.

Reading the Bible or listening to the Bible’s stories, we see how God works in our lives and we get to know what God expects of us. We take our stories with us when we go to the Bible. Similarly, we take Jesus with us when we go to Communion. With more justice we can say, in both cases, that Jesus takes us.

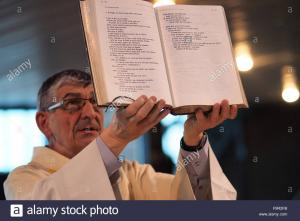

Standing for the Gospel

The lector proclaims the Word. If it is done well, it does not sound like a reading out of a book; it’s in the people’s first language, the language of talking. It sounds like talk, like telling a story. The lector’s voice has the excitement and freshness of someone who has something to say to someone else who is eager to hear it. We celebrate God’s Word in our lives. It is stories that we want to hear again and again, to remember the message, of course, but mostly just to celebrate. We love our stories.

The first three parts of the Liturgy of the Word are usually a story or an instruction from the Old Testament, a Psalm, and another story or instruction from one of the letters of the New Testament. These help set the stage for the one story that makes us who we are, the Gospel story, the Good News of Jesus Christ. At this point we can no longer sit to listen. We need to stand up and be this story. It is the story that lived in us before we came to church, the story of God walking with us, wherever we are on this earth. It’s why we came to celebrate, a call to be nourished by hearing someone tell us our story again but also a push from behind and within because it’s the story we live.

Conclusion

In the past one could tell the difference between Protestant and Catholic by the Protestant emphasis on Word and the Catholic emphasis on Sacrament. Catholics almost never held a service of the Word by itself but often had sacraments, for example Baptism and Reconciliation, without any reading from the Bible. Now a celebration of the Word of God is standard with every sacrament.

It’s easy to think of the Liturgy of the Word as a lesson meant to prepare us for the really important part of the Mass—the Communion. But, going back to the early Fathers, the Church has considered the Word of God to be a real presence and activity of Jesus. The Liturgy of the Word extends to us sacramentally the earthly ministry and saving work of Jesus, just as the Eucharist does.

The homily that wraps up the Liturgy of the Word is its most important, and usually longest, part. It differs from the sermons we used to get, teaching us and often admonishing us. A homily is God speaking afresh in the words of the priest or deacon, showing that God’s Word is not just old news but something that is living in the world today. It’s also about where we came from and where we are going. The entire Liturgy of the Word reminds us of the part we play in God’s story and challenges, encourages, and strengthens us for this work.

Think again:

We speak of the presence of Jesus in the Liturgy of the Word. Here are some different ways of thinking about that presence: (1) I identify with words spoken and events that happened long ago; (2) I hear Jesus speaking to me today; (3) I think of how Jesus works in me today. How do you experience the presence of Jesus in the Liturgy of the Word?

We used to call the priest’s talk after the Gospel a sermon. What do you think is the difference between a sermon and a homily?

Image credit: Alamy Stock Photo via Google Images