You can tell from these posts on the Mass that I view the liturgical reform since Vatican II positively. I think most Catholics do too, but many do not. That fact became clear to me last week. My sister mailed me some articles that a priest of the Wisconsin parish where I grew up published in the local newspaper. The articles, she says, disturbed many Catholics. My response to him, which that newspaper may or may not print, also makes up for my ignoring until now the existence of these contrary voices.

Father laments the results of a recent PEW survey showing many Catholics’ loss of faith in Christ’s presence in the Eucharist. Liturgical reform is at fault, he thinks. This includes priest facing the people, the disappearance of the Communion rail, Mass entirely in English, and even congregational hymn singing. He would like to see a trained choir singing Gregorian chant, Latin in at least some parts of the Liturgy, and priest “ad orientem.” That means (symbolically) facing toward the direction from which Jesus will return and (really) praying most of the time with his back to the people on the other side of a Communion rail.

The data in that PEW survey are astonishing. Less than a third of Catholics surveyed stated they know and believe Christ is truly present in the Eucharist. Over two thirds believe that presence is merely symbolic. The percentages are reversed for Catholics who attend Mass weekly. But still it’s disturbing that a third of Catholics at a typical Mass don’t know what they’re doing there. Sadder, and sadly ironic, is that this happens even as Catholics are learning about the many Protestants who do believe in Christ’s real, not just symbolic, presence in the Eucharist.

A Eucharist story from before the reform

My thoughts go back to the 1950’s, before liturgical reform, and a Catholic boy getting up from kneeling at the Communion rail. He has just received “the Body of Christ” on his tongue. Today he’s having trouble swallowing the sacred host without chewing it. That would be irreverent. As the appearance of bread threatens to dissolve in his mouth, he thinks of what he has been taught. Christ is really there but only as long as the sign of bread remains. By the time he gets back to his pew, he has successfully swallowed the host. Then he quietly meditates on the gift of Jesus’ presence within him, wondering how many more seconds or minutes that will be, as digestive juices work on the host.

This story says something true about Catholic Eucharistic belief, but it leave an impression that is at odds with that faith. It seems to say that Jesus is present in the form of bread in the same way any hidden physical thing might occupy its particular space and time. The sign, bread, has, contrary to appearances, become the reality of Jesus. This is about as far as most Catholics’ understanding of the real presence goes, whether they believe it or not.

Failure of education

For me the starting point for better understanding the Eucharist was to know the signs of the Eucharist more exactly. They are not simply what looks like bread and wine. Rather, the signs are bread broken and shared, a cup passed and shared. The signs of the Eucharist are actions that a worshiping assembly takes together. It’s the “Lord’s Supper,” an ancient name for the Mass. It’s the “Breaking of the Bread,” another ancient name and another way of saying to share a meal together. Jesus is present, contrary to the appearance of bread; but the actions going on all around do seem a lot like God at work.

Catholics, but not Protestants, also believe Jesus is truly present in the tabernacle, where consecrated bread that was not consumed at Mass reposes. Even here, while the sign of bread is perfectly still, there is an active meaning. Jesus is not at home here as if in a castle. The tabernacle, a word that once meant tent, is a place from which Jesus is poised to go out to serve the needs of the sick or dying. Taking Communion to the homebound was the original purpose of reserving some of the sacred hosts.

Going back to that memory of having trouble swallowing the host, I needn’t have bothered about how many minutes or seconds the host would retain the form of bread. Jesus was present in the common action of that gathered community, in the meal that was shared. Most of us thought individualistically. But Jesus comes to us together, as a body. Only, the liturgy in those days didn’t show it very well, and today most of us still don’t understand it very well.

An active presence in active signs

Today the liturgy has powerful ways of showing the reality of Christ’s presence in the shared action of the assembly. The Communion procession involves communal singing of a hymn. Holding hands open to receive Communion symbolizes, as well as holding one’s tongue out does, that we are receiving a precious gift. But standing symbolizes better than kneeling that we involve ourselves in Christ’s action. Taking away the Communion rail brought us Mass-goers closer to the action of the Mass.

The same can be said of the priest facing toward the people. This orientation shows clearly the relationship between priest and people. The priest, representing Jesus, the head of the body, is not just the most important celebrant, without whom there cannot be a Mass. He is presider, the leader of the worshiping assembly, drawing together and honoring the various contributions of all the members, without which there cannot be a Mass. None of this comes across when the priest simply faces forward, like any of the rest of us.

Finally, if the Mass is truly the work, with Christ, of God’s holy people—which “liturgy” literally says—then it only makes sense that that work be conducted in the people’s language. Once we thought that the Mass had to be in Latin, a dead, language, because living languages are always changing. Such changes might eventually distort the meaning of the Mass text. That seems an unnecessary worry, but just in case there is still a Latin Mass text, against which experts can check translations that parishes use.

What the people contribute counts

Besides solving a problem that doesn’t exist, Latin in parish liturgies erects another barrier between the people and the Mass. While the priest says the words in Latin, the people may follow along with translations in their “missals.” Whether they do this or not, the Mass goes on because the supposedly “real” Mass is what the priest, with his back to the people, says and does, mostly inaudibly and invisibly. There will be bells announcing important parts of the ceremony. At the Consecration, a raised host and chalice will offer the people the ability to see and adore. But these are poor ways of saying that I in my pew really need, for the Mass’s sake, to be there.

We hear repeatedly, when there are complaints about poor, lifeless liturgies, that it’s not what we get out of the Mass but what we give to it that counts most. I believe that’s true, and I rejoice in the kind of active participation in liturgy, in many different roles, that the Church’s liturgy invites me to.

What about the big issue, liturgical reform and faith in the real presence?

The new form of the liturgy does not support most Catholics’ understanding of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist as well as the old did. We don’t, typically, have as much time to silently adore Christ present in the raised host at the Consecration. Most of us don’t kneel for Communion, although we can if we wish. Now instead of silently meditating on Jesus, dwelling for a time within our individual bodies, we join together in a robust (preferably) singing of a Communion hymn. These are problems for belief in the real presence, though, only because liturgical reform has not come with adequate understanding.

Today’s liturgy does strongly support an experience of Christ really present in assembly gathered and working together, priest presiding, word proclaimed, Living Bread broken and shared, and Saving Cup poured out for all. In short, Christ is present and active in the work of God’s people.

The odds of 100 percent of church-going Catholics saying they believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist would be greatly improved if they understood two things. First, their experience of liturgy embodies a truly active presence of Christ; it actually looks like Christ at work. And, second, in many ways that presence in bold actions of a worshiping assembly points to God’s work in the midst of their faith lives outside of the Liturgy. But that last part is a subject for another long story, toward which this series is heading.

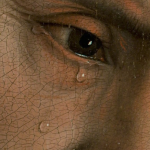

Image credit: New Liturgical Movement via Google Images