I first met Thomas Merton in his early book Seeds of Contemplation. I was a philosophy student in the 1960’s, wondering how such an airy pursuit could matter in a time as troubled as the one I lived in. Merton’s life spanned a lot more trouble than mine had, but he managed to satisfy both my need for peace and my urge to explore the terrain of thought. It didn’t hurt that I found in and behind Seeds echoes of Thomas Aquinas, whose philosophy my teachers tried to instill in me. I was yet to learn of the Thomas Merton who engaged a much wider world of thought and action.

This is the third in the “Ordinary Radicals” series. Here is what Common Prayer: A Liturgy for Ordinary Radicals says about Thomas Merton in its December 10 entry:

Thomas Merton pursued the ideals of pleasure and freedom in early adulthood only to reject them as an illusion and embrace a life of prayer and silence as a Trappist monk. His 1949 conversion story, The Seven Storey Mountain, was a surprise bestseller, introducing millions of modern people to the gifts of monasticism. A mentor to many activists in the Catholic peace movement, Merton became a prophetic voice for peace and nonviolence in the twentieth century, despite the fact that his order censored his “political” writings. Convinced that contemplative life must engage the world, he prepared the way for a new monasticism.

Some facts about Thomas Merton:

- Thomas Merton was born January 31, 1915, in Prades, France, of a New Zealand-born father and an American-born mother, both of them artists.

- For 20 years Merton moved between New York and various locations in France and England. Studying in Cambridge “preferred drinking and bumming around … was frequently in legal trouble, and … fathered a child outside of marriage—a child he never met.” (Alan Jacobs in The New Yorker)

- He entered the Catholic Church in 1938 after a dramatic conversion experience while a student at Columbia University. On December 10, 1941, he joined the Abbey of Gethsemane and the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (Trappists).

- He wrote over sixty books and hundreds of poems and articles. His literary output spanned topics from spirituality and Western and Eastern religions to civil rights, nonviolence, peace, and nuclear arms.

- He died on December 10, 1968, accidentally electrocuted while attending a conference near Bangkok, Thailand, on East-West monastic dialogue.

More on the man of contradictions

- James Martin, writing for Loyola Press, describes a “man of contradictions”:

He struggled “with his own vocation while touting the virtues of monastic life.” He battled superiors “while writing about the value of obedience.” He desired travel “while simultaneously treasuring his seclusion.” He sought “the company of others while loving his solitude.” He planned “book after book even as he believed that writing tempted him greatly to the sin of pride.”

- A Hindu monk urged Thomas Merton to delve into his own Christian tradition. Soon after his Baptism, Merton told friends he wanted to be a priest. Martin in the New Yorker article says, “They found this rather comical, given his ongoing interest in women.”

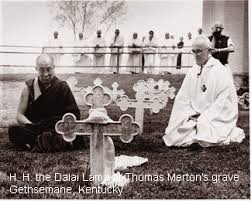

- The Dalai Lama praised him for “a more profound understanding of Buddhism than any other Christian he had known.”

- He dedicated his life to God and to the Church. Yet he experienced awe at statues of the Buddha in Sri Lanka. He wrote: “I was suddenly, almost forcibly jerked clean of the habitual, half-tied vision of things, and an inner clearness, clarity, as if exploding from the robes themselves, became evident and obvious.”

- The abbey of Gethsemane says: “He was one of the first Catholics to commend the great religions of the East to Roman Catholic Christians in the West.”

- Merton became friends with a novice from Nicaragua. They planned to move to Mexico and there establish a new monastery. It would seek justice “in the grossly unjust societies of Central America.” Superiors refused Merton’s request to move. The novice, Ernesto Cardenal, became a priest and minister of Culture in Nicaragua’s Sandinista government. Pope John Paul II defrocked him when he refused an order to quit politics. Merton got permission to move to a two-room hermitage in late 1961.

Later writings

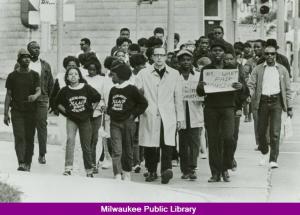

Thomas Merton continued to engage the political issues of the volatile 1960’s. The Berrigan brothers, Daniel and Philip, could not convince the one they considered their mentor to join their protests. Instead, Merton wrote from his secluded place politically trenchant works like:

- “Original Child Bomb” on the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,

- an elegy for four girls killed in a Birmingham Baptist church bombing,

- Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander.

- and No Man is an Island (not even in a hermitage).

Merton’s last trip away from the monastery was in pursuit of his growing interest in the relationship of Christianity to the other great religious traditions, especially those of the East. In 1968 his superiors asked him to meet in Asia with monastic figures in other religious traditions. As Martin quotes his journal:

Joy. We left the ground—I with Christian mantras and a great sense of destiny, of being at last on my true way after years of waiting and wandering and fooling around. … May I not come back without having settled the great affair. And found also the great compassion, mahakaruna. … I am going home, to the home where I have never been in this body.

If the “great affair” was the relationship between Christianity and Buddhism, Merton may have settled it, but only in a dream. He wrote:

Last night I dreamed I was, temporarily, back at Gethsemani. I was dressed in a Buddhist monk’s habit.

Soon after, slipping as he stepped out of the shower, Thomas Merton grabbed an electric fan trying to reach for support and died.

Image credit: Tibet House US