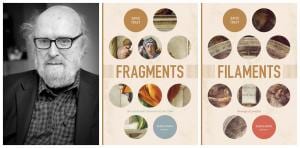

Out This Year — Fragments: The Existential Situation of our Time and Filaments: Theological Profiles

For a David Tracy fan, it’s been a long wait – 25 years since his last book. This year Chicago University Press published a two-volume collection of Tracy’s essays. Since his last book, On Naming the Present: God, Hermeneutics, and Church, the academic world has been waiting for the “God book” that Tracy has been promising. It doesn’t appear that these collections of essays are it. However, I don’t think these books are the last that David Tracy has to offer.

I knew Fr. Tracy from my student years in philosophy at The Catholic University of America. In the midst of finishing his doctorate at Gregorian University in Rome, he undertook his first teaching assignment there. In the course of two years he so impressed his theology students that they compiled and published notes from several classes. I still have my copies of those notes.

Why this series … a dedication

David Tracy and his new publications will be occupying my blog for quite some time, so an explanation is in order. I have known Fr. Tracy for a brief period in person and much longer through his books and articles and even You Tube. In that time I’ve come to this conclusion: David Tracy has never met an honest thought or point of view that he couldn’t engage in an honest and fruitful conversation. That fruitfulness is for Tracy himself as well as for his conversation partner. Conversation is the largest, though not only, part of Tracy’s theological method. And honest means the ultimate in respect for the other as other, not a confused or simply inferior version of the self.

Two very important people in my life are a daughter and a nephew, both of whom, in their honest and thoughtful ways, have left the Catholicism of their early years. I can’t read very much of David Tracy without thinking of one or the other of them. It might be Tracy’s opposition to totality systems, what my nephew calls “isms.” As the title of the first of the new books says, Tracy likes fragments instead. Not a “consoling ism” but an “awesome and terrifying hope beyond hope” might help us to name God. Or it might be his rejection of imperialisms that often lay claim to “absolute truth.” My daughter just might appreciate Tracy’s non-authoritarian notion of truth. She’s also like his turn to the oppressed non-white, -male, -Western “other,” including the natural world, for their strong, destabilizing fragments.

Since these two souls are so much on my mind, it’s to them that I dedicate this series.

Helping David Tracy

Doing justice to Tracy’s thought will be a struggle for me. Tracy writes for professional, academic theologians—I’m an amateur at best. But he insists that theology has three publics – the academy, the Church, and society. That last public may be the most important. Along with Tracy I’m convinced that religion must converse with the world in something like a common language. It’s theology’s job to help religion do that. That view is more common among Catholic theologians than Protestants, but it’s far from unanimous in either tradition. The alternative is for a religious body to speak its own language to its own members, not in order to shut the world out but to grow into the kind of body that will invite others in. Tracy argues, instead, for a religion that goes out to meet the world in mutual understanding and, where necessary, mutual criticism.

My job in this blog series will be to help Tracy help religion have this conversation with the world. Simplifying Tracy, of course, risks oversimplifying and, in my case, getting things wrong as well. On the other hand, “I don’t think I’m that obscure” is Tracy’s response to quips about his writing style. Indeed, my first quick reading of Fragments finds some of Tracy’s most abstract discussions suddenly but seamlessly veering into areas that politicians, economists, and ordinary people often think about.

David Tracy, “God-obsessed” and broadly human

I marvel at the breadth of Tracy’s interests and his ability to bring a variety of resources to a problem. Wondering about the person behind all this learning, I turned to Wikipedia and a David Gibson article in Commonweal, “God-obsessed: David Tracy’s Theological Quest.”

David Tracy was born January 6, 1939, in Yonkers, New York. His father was a union organizer. Wikipedia says he loved to read to his three sons from historian Henry Adams, of the family with the two presidents. Tracy entered the high school seminary for the Archdiocese of New York in 1952. There he nurtured a strong love for literature. “He read all the time, and he read very widely,” a fellow seminarian says. After eight years, equipped now with a classical as well as religious education and a B.A. in philosophy, he entered theology studies at the Gregorianum in Rome.

It was the time of the Second Vatican Council. Tracy was ordained in Rome in December 1963. He spent a year as a parish priest in Stamford, Connecticut, then returned to Rome to pursue his second calling, to the academic life. Gibson relates a couple incidents from that parish experience:

- A parishioner, the conservative William Buckley, had reservations about the “new Mass.” Buckley recalls how this “very intelligent and bright curate” convinced him to become a lector.

Gibson retells another story:

- A young couple was seeking marriage counseling. The distraught husband called from “exile” at the YMCA one night. “Tracy racked his brain for something to say… [T]he man hung up and immediately called his wife to share the news that the priest had advised him to go bowling. They laughed so much that the ice broke, and they reconciled that very night. ‘And people say I have no pastoral sense!’ Tracy laughs.

An academic life

“Beloved as a priest and highly regarded as a homilist,” the Commonweal article goes on, “Tracy showed his greatest promise as a theologian.” He studied under the great Catholic theologian Bernard Lonergan in the exciting atmosphere of the Second Vatican Council. Tracy received his doctorate in theology from Gregorian in 1969. He had already begun teaching at Catholic University.

Tracy’s two years at Catholic saw controversy erupt. Tracy was one of hundreds of theologians who openly dissented from the teaching of Pope Paul VI on artificial birth control. He was dismissed along with 21 other faculty members. They sued, won their case, and got their jobs back.

Meanwhile Chicago Divinity School, desiring a larger Catholic presence, was offering an opportunity Tracy could not refuse. Tracy rapidly became ensconced there, winning awards and honorary doctorates, joining and sometimes leading prestigious scholarly groups, publishing slowly, and, most important, conversing regularly with world-renowned scholars. Just to name ones famous enough for me to know of, there are or have been at the Divinity School: Mircea Eliade, Langdon Gilkey, Andrew Greeley, and Jean-Luc Marion.

Unlike some other theologians, whom Tracy has dared to defend, Tracy himself has never been disciplined or forbidden to teach in a Catholic institution. Perhaps leaving Catholic U. when he did saved him from some scrutiny. Or it may have been “his notoriously idiosyncratic prose and the complexity of his arguments,” Gibson offers in the Commonweal article. But he hasn’t escaped notice entirely. Another story:

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger approached Tracy after his talk on Vatican II in America. “I hear many different kinds of things about you,” the cardinal said. “Some good, I hope,” said Tracy. “Some,” Ratzinger answered and walked off. Tracy laughs about it today: “I like him. He knows how to leave a room.”

Books and lectures

Of Tracy’s nine books I’m happy to say I have seven—all except the first and the fourth listed below. He has written numerous articles, of which I have a few, and he’s also on You Tube, giving lectures. The eight books are:

- The Achievement of Bernard Lonergan (1970),

- Blessed Rage for Order:The New Pluralism in Theology (1975),

- The Analogical Imagination: Christian Theology and the Culture of Pluralism(1981),

- Talking About God: Doing Theology in the Context of Modern Pluralism(with John Cobb, 1983),

- A Catholic Vision(with Stephen Happel, 1984),

- A Short History of the Interpretation of the Bible(with Robert Grant, 2d. ed. 1984),

- Plurality and Ambiguity: Hermeneutics, Religion, and Hope (1987), 1990.

- Dialogue with the Other: The Inter-Religious Dialogue (1990),

- On Naming the Present: God, Hermeneutics, and Church (1994).

This web page links to David Tracy on You Tube, giving the following lectures:

- Faith in God and Church Order: The Catholic Case of Martin Luther, Nov. 13, 2003

- Tragic Vision: The Abandoned Vision of the West? Oct. 2, 2017

- Father David Tracy Receives the Sacred Heart U. Medal – Part 1 and Part 2, July 11, 2010

- God as Infinite: Ethical Implications, June 2014

- Augustine: Theological and Philosophical Conversations, Dec. 17, 2015

- 2016 Costan Lecture at Georgetown University, “Gregory of Nyssa, An Infinite, Incomprehensible, Infinitely Loving God” Feb 20, 2017

- Zabriskie Lecture: “Philosophy and Theology: Descartes and Fenelon on the Infinite God, Sep. 5, 2017

- Theology and Mysticism, Oct. 25, 2018

Final thoughts about and by David Tracy

- Richard McBrien (theology chairman, Notre Dame): ”Tracy reaches beyond theology into the cognate sciences and returns to theology with new questions as well as new answers. He is very creative because, more than any other theologian, he really does understand modern philosophy, literature and language, and he can see connections nobody has seen before.” (From Eugene Kennedy, “A Dissenting Voice: Catholic Theologian David Tracy,” New York Times article)

- Along the same line, the Commonweal article says, “Tracy will invoke Euripedes and Derrida, Ricoeur and Nietzsche, Simone Weil and Saturday Night Live all in the same riff, and somehow it all makes sense, even if you’re not always sure how.”

- Scott Holland quotes Tracy revealing one of his major concerns: “God reveals Godself in hiddenness: in the cross and negativity, above all in the suffering of those others whom the grand narrative of modernity has set aside as non-peoples, non-memories, in a word, non-history.” (from “This Side of God: A Conversation with David Tracy,” by Scott Holland.

Image credit: University of Chicago Press via Twitter