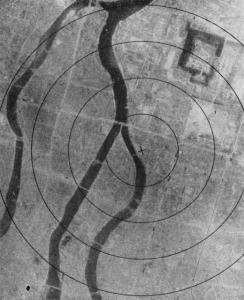

It’s been 77 years since the only use of nuclear weapons in warfare. On August 6 and 9, 1945, the United states dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I’m returning to a subject I treated previously. This post will begin a series on “Nuclear Weapons, the World, and the Church.” Four posts in this series will cover these topics:

Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the conscience of World War II victors

The pragmatic case for the bomb falls apart

Nuclear Weapons Today: The Moral Issue

Moving away from Armageddon: one reasonable step

Dedication: In 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, Marking the first use of a nuclear weapon against people. As we remember the transfiguration of Christ in the mysterious light of glory, we also remember all those who were tragically and senselessly transfigured by the first nuclear blast. May their memory help us to see a way toward peace in our time. (From Common Prayer for Ordinary Radicals)

From global warming to the pandemic to the health of democracy around the world, many issues crowd thoughts of nuclear peril into the backgrounds of our minds. Yet that peril hasn’t gone away.

Major nuclear powers, especially the U.S. and Russia have backed away from previous agreements limiting and reducing nuclear stockpiles. Plans are moving forward to spend trillions upgrading and even replacing nuclear weapons delivery systems. In the midst of his war in Ukraine, Russian President Putin hints at possible use of nuclear weapons.

The Doomsday Clock

The Doomsday Clock began as a project of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. They had worked on the Manhattan Project and knew what a terrible force they could be unleashing on the world. They tried but failed to convince the U.S. secretary of war not to use the bomb against inhabitants of a Hiroshima or a Nagasaki. Instead they had proposed a demonstration in an uninhabited area. After the war they worked to inform the public about science and “its implications for humanity.”

The initial setting of the clock, in 1947, was seven minutes to midnight. Not claiming that seven minutes was all the time left before nuclear Armageddon, but using a metaphor to depict existential threats to humanity. That seven minutes becomes a basis for comparing how imminent these threats are compared to 1947.

Immediately after World War II, the threat was nuclear war. Since then climate change and disruptive technologies like ”bio- and cybersecurity” have become existential concerns as well.

Seventeen minutes is the furthest from midnight the clock ever got. That was in 1991 after the Soviet Union collapsed and after the signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. The closest to midnight was 100 seconds in 2020. That setting hasn’t changed since.

Early Catholic opposition to the Bomb

Searching for information on early Catholic response to the use of the atomic bomb in World War II, I encountered an authority I have known personally. Msgr. John K. Ryan taught one of my philosophy classes at The Catholic University of America in the mid 1960’s. A much younger Fr. Ryan, three days after the second use of an atomic bomb, wrote in the Arkansas Catholic:

The story of the atomic bomb should fill us with dismay. (“Emma Catherine Scally, “Between Piety and Polity: The American Catholic Response to the First Atomic Bombs”)

While the bomb was in development, Pope Pius XII showed he well understood the power hidden inside the atom. The New York Times quoted the pope in 1943:

Above all, therefore it should be of utmost importance that the energy originated by such a machine should not be let loose to explode—but a way found to control such power…. Otherwise there could result not only in a single place but also for our entire planet a dangerous catastrophe.

In 1948 this pope called for a ban on the atomic bomb, “the most terrible arm which the human mind has thus far conceived.” (New York Times article) The Pope reviewed the ancient teaching of the Church, including this provision:

The use of force must distinguish between the militia and civilians. Innocent citizens must never be the target of war; soldiers should always avoid killing civilians. (From “Just-War Theory,” article on the Mount Holyoke College web site)

The pope continued:

If the wars of those days already justified such a severe sentence, with what words should we today judge those which have struck our generations and placed at the service of their work of destruction and extermination a technique incomparably more advanced?”

More than one Catholic position

But in the early years after the war the American Catholic response to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not one-sided. The U.S. Army’s Catholic chaplain Fr. George Zabelka, blessed the weapon which would fall on hundreds of thousands of Japanese, Catholics included. A Catholic pilot flew the bomber that carried the bomb to its destiny. American Catholics divided on the subject of the bomb.

That division nearly disappeared after 1949, when the USSR tested its first nuclear weapon. Catholic ambivalence turned to majority Catholic support, as people believed the bomb protected us against the Communist enemy. Prominent Catholics seriously debated the possibility of moral use of nuclear weapons, contingent upon the accomplishment of a greater good relative to the harm done.

Even the pope tailored his views on nuclear weapons to his audience, preferring not to offend.

Although the L’Osservatore Romano, Rome’s official newspaper, had published an editorial that harshly criticized President Truman’s decision to use the bomb, the Pontiff retracted similar statements that were published in the Stars and Stripes, a newspaper for soldiers, and classified them as “not authorized.” (From Emma Catherine Scally, “Between Piety and Polity.” Her article is the source for this section.)

The morality of the bomb was never a matter of pure ethical theory but depended on conditions “on the ground.” Was the nuclear strike necessary? How much damage to human life occurred, and was that proportional to the just goal of the war? Catholic ethics can be very pragmatic.

The next post in in this series will show how attempts to justify the bomb pragmatically fail.