The Healing of the Paralytic (Gospel of Mark 2:1-12) is Jesus’ challenge to the oppressive ways of the temple and its officials.

This is the third in a series on William R. Herzog II’s Jesus, Justice, and the Reign of God. It considers the first half of Chapter 6, “Something Greater than the Temple is Here.” (Pages 111-132) Previous posts in this series are:

- The Historical Jesus and the Transcendent God in the Work of William Herzog

- Context Groups Continues the Long History of Witnessing to Jesus

In the ancient Mediterranean world temples were as much political and economic as religious institutions. The temple in Jerusalem was no exception to that rule, and it was as powerful as the political and economic elite could make it. The temple held a prominent place among institutions that oppressed the poor in Palestine. For Jesus the temple was an obstacle to God’s reign.

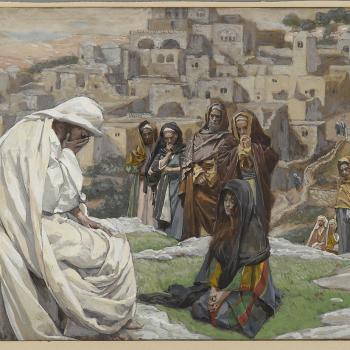

A previous series of posts (concluding here) showed how Jesus’ teaching in parables exposed the ways oppression operated in first-century Palestine. In the current series it’s Jesus in action that exposes and opposes oppression. In the healing of the paralytic Jesus does more than help a poor invalid. He demonstrates God at work in a space not controlled by the temple and its officials.

The Healing of the Paralytic: the story in two parts

The story of the healing of the paralytic has two parts, and scholars have argued about how and whether they fit together. There is a healing and an argument with scribes about forgiving sins. In the following summary I separated the two parts. The argument (part 2) interrupts the healing story (parts 1 and 3).

- The paralytic comes to Jesus. Jesus is at home in Capernaum, and the crowd that gathers is spilling out the door. Friends of a paralytic dig a hole through the roof and lower him down in front of Jesus. Jesus sees their faith. (Mark 2: 1-5a)

- Forgiveness of sins and the ensuing argument. Jesus says, “Son, your sins are forgiven.” Some scribes think it’s blasphemy: “Who can forgive sins but God alone?” Jesus replies, “Which is easier, to say to the paralytic, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or to say, ‘Stand up and take your mat and walk’? But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins” –

- The healing. … he said to the paralytic – “I say to you stand up, take your mat and go to your home.” He stands up, takes his mat and goes out, and all are amazed and glorify God.

A common analysis and a response

A common opinion among scholars is that parts 1 and 3, the healing story, came first. Its vivid details, like the tearing through the roof, convince some that it’s an actual memory, not a made up preacher’s tale. The argument over forgiving sins may have been made up, although it likely illustrated controversies Jesus actually had. Later between early Church and Synagogue a controversy over the Christian practice of forgiving sins also arose. In defense of Church practice, Mark spliced an argument between Jesus and scribes into a previously existing healing story.

There is evidence to support this view. The argument seems to break in unexpectedly. Just where you would expect Jesus to pronounce words to heal the man’s paralysis, he says instead, “Your sins are forgiven.” The argument follows. Then an awkward phrase, “he said to the paralytic” gets the story back to the healing. Finally “all” are amazed and glorify God. That “all” makes it look like the contrarious scribes have suddenly disappeared. Or they were never there in the first place.

Not everyone agrees with this analysis. The seemingly awkward phrase “he said to the paralytic” resembles another parenthetical insertion into a narrative by the Gospel writer Mark. (Mark 13:14 – “let the reader understand”) Maybe for Mark and his readers it’s not so awkward. Mark says “all” were amazed and glorified God, but that (in my opinion) could be the way Mark typically ends a miracle story. The scribes may have been there, but Mark just ignores them.

A bigger issue is the shift from the expectation of bodily healing to sins forgiven. Does that accord or conflict with what a “crowd” following Jesus would expect? And is there a likely setting in Jesus’ life and work for an argument about sins being forgiven?

The story’s (possible) setting in the world of Jesus: healing illness vs. curing disease

There’s a difference between curing and healing that we generally don’t recognize. We cure a bodily disease. Healing is broader. It’s for the whole person, body, soul, spirit, and notably, in first-century Palestine, the person’s place in society.

The crowd surrounding Jesus knew that the paralytic was sorely in need of healing in its broad sense. That included restoration as a respectable member of society. As a paralytic unable to work, he could not pay the temple tithe. The scribes’ oral interpretation of the Law in the Scriptures made tithing a requirement of purity. That put the paralytic, along with most peasants and laborers in Palestine, into the class of sinners. To be poor was about the same as being a sinner.

The paralyzed man was doubly cursed. Besides being poor, he was impaired in body. In the dominant view only “whole” bodies were ritually pure. And only ritually pure Jews were allowed in the temple. Even if he had the money to pay off his religious debt, his impaired body would have kept him out of the temple.

This common situation may have been uppermost in the minds of the crowd following Jesus. Many of them would have been in the same despised condition as the paralytic. It would not be a big surprise to them if Jesus addressed this issue first, saying “Your sins (in this case your debts) are forgiven.”

The setting again: the conflict with the temple

Herzog takes several pages to identify a setting in Jesus’ life for a controversy over forgiving sins. You might wonder why he had to take so much trouble. The scribes were on solid ground theologically when they said only God could forgive sins. If Jesus claimed to be able to forgive sins, then controversy and the charge of blasphemy would easily follow. Even a miracle doesn’t help Jesus because, as we see later in Mark’s Gospel, scribes could give the devil credit for that.

A closer look shows that Jesus is not pretending to be God or claiming to act like God. His words are “Son, your sins are forgiven.” The action is God’s, not Jesus’. In short, he is only doing what the temple does all the time – announcing God’s forgiveness. But the scribes get so upset that they wrongly accuse of him of blasphemy. What was the real issue for those scribes?

Scribes were among the small group of literate Palestinians. Among their jobs was the keeping of records, like who owed what to whom, including to the Temple. Their interests would have coincided with the temple officials and other creditors for whom they kept records. The scribes saw in Jesus’ action a challenge to the temple and their own status.

Patrons and clients

A patron-client system facilitated much of the business of first-century Palestine. Herzog describes:

Patrons were wealthy aristocrats who provided economic benefits to the poor in return for the services they could render…. But, in addition to the clientage of the poor, patron-client networks included everyone…. [T]he wealthiest and strongest offered patronage to less wealthy aristocrats…. The poor seek patronage to ensure their survival, and the rich seek clients to enhance their social prestige and power. (p. 127)

In an analogous way Yahweh was the patron of the entire Jewish people. But, as in human relationships, you didn’t go to the top boss to solve your problem. You went through intermediaries, called brokers. Temple priests claimed to be the sole brokers of Yahweh’s favors. You had to go through the temple for assurance of fertile lands, timely rains, etc. Of course, that’s exactly what a poor peasant in debt to the temple couldn’t do. You had to pay the temple to get God’s favor, but without God’s favor, i.e. an unusually bountiful harvest, you didn’t have money too spare for the temple. With all the other fees and rents and taxes that the elite exacted, it was a no-win situation for the poor. And the reigning ideology blamed the poor person and his impure state rather than the system that kept him poor.

Jesus declares God’s forgiveness free of charge and independent of the temple. This is not just a matter of sins in the abstract or personal sins that scribes could easily ignore. Jesus is stepping into dangerous territory. It’s too close to the wide-ranging – and widely ignored – debt forgiveness of the Scripture’s Jubilee and Sabbatical years. The finances and the power of the temple and of anyone whose interests align with the temple are at stake.

Jesus and the temple

In Jesus’ theology grace goes ahead of the temple. Certainly ahead, at least, of the current temple establishment with its high priest and regular priests, scribes, and their interpretation of the Scriptures. In Jesus’ theology God’s grace is free.

What if the temple establishment were to undergo reform, even a reform to Jesus’ liking? Such reform would lift Jesus preferred Scriptures, the prophetic compassion for the poor, above purity concerns. Would temple reform be enough for Jesus? Or was the charge against Jesus at his trial—that he threatened to destroy the temple—correct.

In Mark’s Gospel Jesus predicts a destruction of the temple so complete that not one stone is standing on another. Was that just a prediction or more like a program or, perhaps, hopeful thinking on Jesus’ part?

In Capernaum, where the healing of the paralytic takes place, Jesus is far from the temple. He will eventually make his way to Jerusalem and there engage in a kind of civil disobedience in the temple. The meaning of that act will be the subject of the next post in this series.