“Destroy this temple and I will rebuild it in three days.” (John 2:19) Could Jesus, once a village handyman, have meant that literally? What would the temple that he built in three days be like?

This is the fourth post on William R. Herzog II’s Jesus, Justice, and the Reign of God. Earlier posts in the series are:

- The Historical Jesus and the Transcendent God in the Work of William Herzog

- Context Group Continues the Long History of Witnessing to Jesus

- Jesus Heals a Paralytic and Opens a Temple-Free Zone of Grace

This post claims it’s possible that:

- Jesus claimed to be able to rebuild the temple in three days.

- He was not referring to the “temple of his body” (as in John 2:21) or to his resurrection after three days.

- He meant a literal temple, one that could be built in three days.

- There is a setting in Jesus’ life where all the above makes sense.

I’m getting help from William Herzog and others as I explore these suggestions.

The charges against Jesus – true and false

Jesus’ trial featured three charges against him, and the charge that led to his execution was not true, Herzog says. Jesus did not claim to be “king of the Jews” as Pilate’s inscription on the cross read. But Herzog thinks two other charges – forbidding payment of tribute to Caesar and threatening to destroy the temple – were accurate enough. The last of these is of interest here.

If Jesus didn’t exactly threaten to destroy the temple, he came close to it. He declared the temple superfluous when he announced forgiveness of the paralytic’s sins. (See previous post.) Jesus attacked the temple again with his line about faith moving mountains. It wasn’t just any mountain that Jesus meant:

Have faith in God. Truly I tell you, if you say to this mountain, “Be taken up and thrown into the sea,” and if you do not doubt in your heart, but believe that what you say will come to pass, it will be done for you. (Mark 11:23, my emphasis)

Ched Myers in Binding the Strong Man (p. 305) says Jesus meant one particular mountain – the nearby Temple Mount. The threat to the temple was subtle but easy enough to read.

Again Jesus’ enemies could have read a criticism of the temple into Jesus’ comment about the “widow’s mite.” (See Myers, Binding, p. 321-22) Its placement in Mark’s Gospel just before Jesus’ prediction of the temple’s destruction, suggests that was probably Mark’s interpretation, too. The Temple took a poor widow’s last two coins – “all she had to live on,” in Jesus’ angry words. (Mark 12:44)

The prosecutor in Jesus’ court case couldn’t get his witnesses to agree. Other than that, he had a strong case. Jesus’ words and actions concerning the temple were indeed threatening. Even without the most provocative episode, which is:

The demonstration in the temple

Herzog interprets Jesus’ violent action in the temple in the light of the huge role the temple played in the Palestinian economy. The temple controlled vast amounts of money and continued to accumulate more. All that money didn’t come just from the shekels that tithing brought in, although that was considerable. The temple was also a bank for the Judean elite. Excavations near the Temple Mount “have revealed the great luxury in which these rich folks lived.” (p. 137)

First-century economies didn’t grow as a modern economy can. In a no-growth economy riches came only with the impoverishment of the lower classes. Upward transfer of wealth begins with interest-bearing loans, especially, but not only, to peasant farmers. Both the aristocrats themselves and the temple bank on their behalf used money to rake in more money. Debt was a constant in the life of the poor. That was “as much because the rich landowners needed to invest surplus income profitably as because the poor needed loans to survive.” Almost inevitably, for farmers, piling up debt meant eventual confiscation of their land. For

… the only logical reason to lend was … the hope of winning the peasant’s land by foreclosing on it when the debt was not paid off as agreed.

That agreement included a provision that nullified the Scripture’s Sabbath and Jubilee Years, when loans should have been forgiven. This provision, the “prosbul,” Herzog comments, “testified to the breakdown in social ties between debtor and creditor….” (p. 137) No wonder, he adds, that the rebels in the Jewish revolt of the 60’s burnt all the debt records the temple kept.

The temple’s visual representation of a stratified society

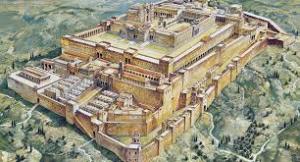

Jewish society separated people according to degrees of holiness, or purity. The temple complex represented this separation with “increasingly inaccessible courtyards.” These separated “Gentiles from Judeans, women from men, Levites and laity from priests, and the high priest from ordinary priests.” (p. 116) Each degree of holiness found its place in a physical hierarchy of ascending spaces.

Imagine Jesus approaching the temple on the day he planned for his symbolic attack. He starts outside Jerusalem in a nearby Judean town. Like all Judea, Bethany was a holy place compared to the lands of the Gentiles. Jesus travels uphill to the holier city of Jerusalem. Within Jerusalem is the Temple Mount, still more holy. He passes a rampart into the temple’s outer court, the Court of the Gentiles. If Jesus were to go on and up, he would ascend to the Court of the Women, then to the Court of the (men) Israelites, which includes the Levites. Beyond and above this, to higher and holier levels, Jesus would never go because he is not a priest. (p. 119)

This day Jesus stops within the Court of the Gentiles. There he sees a warning sign in three languages

… announcing the death penalty for any person, except a ritually clean Judean, who attempted to [continue on]. (p. 117)

And Jesus is ritually unclean, having been in close contact with lepers recently. (He’s been staying at the house of Simon the Leper in Bethany. His temple enemies wouldn’t follow him there.) Along with Jesus, other ritually unclean individuals could gather in the outer court—bastards, eunuchs, and anyone lame or not whole in body. And Gentiles, of course, and anyone too poor to pay the temple tithe. The bearers of the paralytic, before Jesus cured him, would have to leave him here.

The right place for Jesus’ demonstration

You might think that Jesus’ symbolic attack on the temple would be more meaningful in the temple proper rather than in the outer court. Because of impurity Jesus isn’t allowed in that more sacred space, but that needn’t stop him. After all, Jesus did tell a story about a repentant publican who dared to enter where he didn’t belong. (See this post.) Jesus has a better reason for conducting his demonstration where he did.

The outer court is where all sorts of temple business goes on. There you buy animals for sacrifice. And there you change impure foreign money to temple coins for purchasing sacrificial animals. I’ve heard that it was all this busy work, and perhaps shady dealings, that offends Jesus. The sight of it stirs Jesus to righteous anger and motivates his attack. Far from it! Jesus has all along known what goes on in this court. It’s no surprise to him. It isn’t even particularly offensive. We have no evidence that the sellers and money changers were cheating anyone. The economic business that takes place there was necessary for the sacrifices, the temple’s religious service to God.

The reason for Jesus’ attack on the temple in the place where Jesus staged it lies, rather, in this quote from prophetic literature, which Mark attributes to Jesus:

Is it not written, “My house shall be called a house of prayer for all the nations? But you have made it a den of robbers.” (Mark 11:17, a combination of lines from the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah)

The temple’s offenses consist in exclusivity inside its limits and robbery outside.

The inclusive “house of prayer”

In this “den of robbers,” (Jeremiah 7:11), Herzog sees not a place where thievery takes place but a “hideout.” (p. 139) The temple’s and all Judea’s aristocracy commit their theft of peasant lands and poor people’s wealth. Then they hightail it to the temple imagining they’re safe from God’s wrath because they pay their dues there.

Jesus insists the temple is not a refuge for robber barons but, (Isaiah 56:7), “a house of prayer for all the nations.” That’s Mark’s version. In Matthew it’s just “house of prayer.” Matthew goes on to name the people whom Jesus welcomes there: the blind, the lame, even children. Besides foreigners and Matthew’s list, Isaiah in Chapter 56 names eunuchs among the forbidden ones whom God, contradicting his own law, gathers. Jesus probably knew he was quoting, in Herzog’s words, “perhaps the fullest Old Testament vision of an inclusive Israel.” (p. 141)

The problem with the temple isn’t just its role in oppressing the poor. Even in its architecture it says “Keep your distance” to people God loves. Jesus isn’t just cleansing the temple. No cleansing, no reform of scribal behavior, can solve that problem. Jesus’ anti-temple works and words aimed, symbolically and mostly implicitly, at destruction. But Jesus may even have said explicitly something like, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will rebuild it.” (John 2:19) Not that he thought he’d ever get that opportunity.

What kind of temple could Jesus build in three days?

Jesus grew to maturity in a family that, probably sometime past, had lost its ancestral land. Joseph was an artisan, a little better off than a day laborer. He made a meager living selling what he could make with his hands. Jesus followed in the handyman’s trade so he knew something about building. He could have gotten a crew together and erected some kind of structure in three days.

It wouldn’t have looked much like the temple that Herod built. But Jesus wouldn’t have wanted it to. That was the style of the grand tradition of the wealthy, aristocratic, elite portion of society, the portion that holds itself higher than the rest. Jesus preferred the alternative, little traditions of the villages. Jesus’ temple would have been all on one level, like the places where villagers met. There leaders and followers met face to face, to adjudicate internal problems or deal with impositions by the great tradition. There they also planned village celebrations and worshiped Yahweh.

If a village had an actual synagogue (they may not have), it probably would not have been a building set aside for just that purpose. Herzog thinks it may have been like the house churches of the early Christians. (p. 145-46) Jesus’ Jerusalem temple would have been bigger. Otherwise it wouldn’t take three days to build it! Or maybe Jesus picked that number because it sounds good and gets a lot of use in popular stories. At any rate, the number wouldn’t have had anything to do with Jesus’ three days in the tomb.

What about the “temple of Jesus’ body” raised in three days (John 2:21)

There is a tendency in the Gospels to defend Jesus against the charges officials and other witnesses brought against him. The synoptic Gospels tell us that the witnesses did not agree with each other. So maybe he didn’t actually talk about destroying and rebuilding the temple, these gospels imply. Or, if Jesus did so speak, the author of the Gospel of John reinterprets: “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up” referred to the temple of Jesus’ body, says John. The raising up, then really meant the bodily resurrection. Jesus wasn’t attacking the temple, says John, but making a prediction.

I see a problem with the temple as Jesus’ body and the raising up as the resurrection. First, Jesus speaks of raising the “temple” as if it’s something he is going to do. But practically everywhere that the Gospels mention the resurrection it’s in the passive voice. Jesus doesn’t raise himself. It’s the Father’s act.

Raymond Brown in An Introduction to New Testament Christology (p. 151) finds another problem. He thinks Jesus must not have predicted the resurrection ever. Jesus was human, like us, in all things but sin. But a Jesus who knows in advance that he would rise soon after he died doesn’t die a truly human death. Here’s Brown:

He would be a Jesus far from a humankind that can only hope in the future and believe in God’s goodness, far from a humankind that must face the supreme uncertainty of death with faith but without knowledge of what is beyond.

Catholics, Brown goes on, believe in a truly human Jesus,

… for whom the detailed future had elements of mystery, dread, and hope as it has for us and yet, at the same time, a Jesus who would say, “Not my will but yours”….

What about the three days in the belly of the whale?

John, the last Gospel writer, had 60-some years for Christians to develop a theology of Jesus’ body. One could expect that theology to influence the interpretation of words that in Jesus’ mouth may have been about only the temple. In other words, John was taking Jesus’ words but saying something else that his later community needed to hear.

But we have much earlier writings, from a community scholars call Q, that show up in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. In one saying that this community transmitted, Jesus refuses to give a sign to “this generation.” Except for one sign, the Sign of Jonah. (Luke 11:29-32 and Matthew 12:38-42) In this early text Jesus also seems to be predicting his death and rising after three days. Jonah, for refusing to preach to the Ninevites, was three days in the belly of the sea serpent. So Jesus will be three days in the “belly” of the earth. Well, that’s Matthew’s version of the story. Luke has the same Sign of Jonah but without the three days inside either sea serpent or earth.

Richard A. Edwards (The Sign of Jonah, p. 80ff) argues that Q got its material from even earlier traditions, where Jesus refuses to give any sign. The Q community itself added the Sign of Jonah, and the sign was that people, just like the chastened Jonah’s Ninevites, were accepting a prophet’s preaching. In this case a Christian prophet. They were joining the Q community. Later Matthew, but not Luke, added the part about Jonah in the belly of the fish and Jesus’ three days in the earth. (For a fuller treatment of the Sign of Jonah, see this post.)

This very early traditions also gives us no prediction of Jesus’ resurrection in three days and no reason think that that’s what the temple saying was about.

Questions about this proposal and for today’s Church

Could Jesus have claimed to be able to rebuild the temple? I doubt that Jesus said he could destroy the temple as the charge in the synoptic Gospels goes. That would have taken a much bigger crew than Jesus could muster. But a smallish crew could have built a temple that Jesus might like, even in three days. I’m imagining Jesus voicing some desire like: “If only this temple would just fall down. (Not one stone left on another!) Give me three days and I could build an appropriate temple, where everybody belongs.”

Imagining the kind of temple that Jesus might have liked—where people’s differences don’t matter—raises some questions for the Church:

- Are there more and less holy spaces in our church buildings? For example, is the sanctuary holier than the nave? I like to imagine a church where the sanctuary lamp honors the altar of sacrifice, the sacrament’s repose in the tabernacle, and the space where God’s people gather. Call the whole space a sanctuary, as Protestants do!

- Are there dividing lines which you need special faculties to cross? Must the priest meet the procession with the gifts in front of the altar, as if to say “Thanks, but I’ll take it from here.” Why can’t ordinary people go straight to the altar with the bread and wine?

- Speaking of “ordinary people” – is there any other kind? Is there really an ontological difference between baptized people and everybody else? Between a priest and a lay person? I wonder if one cause of clericalism and abuse in the Church is the theory, the old theological opinion, about sacramental “marks on the soul.”

Concluding note: Please, don’t take these thoughts about a simple temple that Jesus could build to mean Jesus wouldn’t like elegant churches and impressive cathedrals. Obviously, Jesus wasn’t going to build one of these. That doesn’t mean he would be against architects using their skills to inspire awe in the presence of God.