The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican occurs only in the Gospel of Luke. Prayer is a main theme of Luke’s, and this parable seems to be all about two ways of praying. There’s the humble prayer of the publican and the proud prayer of the Pharisee.

Scholars believe that the Pharisee’s was a decent prayer in that story. He tells the truth about himself and the publican, as he sees it. With a touch of pride, perhaps, but he starts out thanking God, rather than giving himself credit. And he does stand high and apart from the hated public sinner alone at the East Gate. From practically everybody else, too, to judge by his description of his religious practices. God should certainly see this and accept the Pharisee’s prayer. But Jesus says “rather than” he, it’s the humble publican, who can’t claim any credit at all, who goes home justified.

William Herzog II, in Parables as Subversive Speech, sees something besides pride versus humility behind the different outcomes of the two characters’ prayers. It’s not a question of inner disposition but of objective truth in the context of the Palestinian economy. He says we have in the parable two public sinners, only one of which is recognized publicly as such.

In several parables Jesus only draws pictures. He displays the economic, political, and religious oppression of the poor in Palestine. Herzog deals with these dark stories in Part Two of his book. In Part Three he finds some light and hope in another group of parables. The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican is the first of four in this set.

Previous posts in this series on Herzog’s Parables as Subversive Speech:

- William Herzog Reads Jesus’ Parables, Brings them Down to Earth

- Paulo Freire, the “Pedagogue of the Oppressed”: Is This a Good Fit for Jesus?

- Laborers in the Vineyard: A Reading that Doesn’t Blame the Victims

- The Parable of the Wicked Tenants and the Wickeder Landlord

- The Rich Man and Lazarus, or an Oppressor who Won’t be Taught

- The Unmerciful Servant Parable Trashes Messianic Hopes

- The Horrifying – or Tragic – Parable of the Talents

The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican (Luke 18:10-14a)

The Pharisee’s pride and the publican’s humility – that’s the lens through which I learned to see this parable. The lesson: pride is bad; humility good. Herzog says that lesson comes from what Luke added to the parable, rather than from Jesus’ telling of it. Without those additions the parable tells a different story. I’ll get to Luke’s possible additions at the end.:

Two people went up to the temple area to pray; one was a Pharisee and the other was a tax collector.

The Pharisee took up his position and spoke this prayer to himself, ‘O God, I thank you that I am not like the rest of humanity—greedy, dishonest, adulterous—or even like this tax collector.

I fast twice a week, and I pay tithes on my whole income.’

But the tax collector stood off at a distance and would not even raise his eyes to heaven but beat his breast and prayed, ‘O God, be merciful to me a sinner.’

I tell you, the latter went home justified, not the former….

Luke’s additions

Luke adds a conclusion to the parable, which he puts in words of Jesus:

…for everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and the one who humbles himself will be exalted.” (14b)

The lesson is unmistakable and valuable. Jesus probably agreed with it. At least, scholars think he said it, but probably not on this occasion. They see it as an independent saying of Jesus because the Gospels record it, twice, elsewhere. Luke’s point in tacking it on here is also the reason he gives the story a particular audience:

He also told this parable to those who were convinced of their own righteousness and despised everyone else.” (Luke 10:9)

That this audience is an addition of Luke’s is a guess, but a scholarly consensus, says Herzog. I believe some evidence for this guess is that Matthew and Luke seem to have copied from a hypothetical early document. Based on texts that Mathew and Luke have in common but occur nowhere else, scholars believe this document contained sayings of Jesus with almost no context or setting. The Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican is not one of these texts. Still, it seems likely that the tradition passed on other sayings of Jesus similarly without context. Thus Gospel writers, to make a story, had to invent settings and audiences. When Matthew and Luke tell the same parable, they often construct the setting differently.

The audience is important, and Herzog says we can’t rely on Luke to get it right. The upshot is we have no reason to think that this parable teaches humility in prayer unless Jesus’ actual words lead us there.

We have to imagine some audience, and Jesus was mostly with poor peasants and laborers. These probably made up his audience for this parable.

Peasants and laborers hear the parable of the Pharisee and the Publican

Herzog’s interpretive technique is to try to hear a parable as Jesus’ audience would have heard it. I’ll follow that procedure, too. Not on my own, obviously, because I’ve read Herzog’s Chapter 10, some parts more than once. But I’m going to take the liberty of telling the story in a way that I imagine it without slavishly following Herzog. The criterion, for Herzog, is not certainty but a plausible reading, one that can survive additional scrutiny. I think the closer we can get to Jesus’ listeners, the more plausible the reading becomes.

The Pharisee and the publican

The poor of Palestine had definite opinions about Pharisees in general. They hated them, but they also looked up to them. Pharisees were beneficiaries of an economic, political, religious system that enhanced the fortunes of the rich and separated, degraded, and essentially robbed the poor. Yet they represented one of the high echelons of what seemed like reality. You could hate them, but you wanted to be like them. An enterprising few did manage to climb up one or more levels of the hierarchy. With some ability and not too much caring about whom they stepped on, they could work for a government official, landowner, or middle level bureaucrat.

Such I imagine was the publican of Jesus’ story – a collector of tolls or taxes. He was now part of society’s hierarchy. His job was to collect whatever his immediate superior demanded. Of course, he needed to squeeze a little more out of his district’s patrons for himself and his family. His superior, in charge of several districts, had his own boss he needed to pay. He also needed something for himself—somewhat more than his underlings in keeping with his higher place in society.

The point is, the publican is part of a hierarchy but at the very bottom, just barely able to make ends meet. He would be the one in daily contact with the unprivileged crowd and be hated the most.

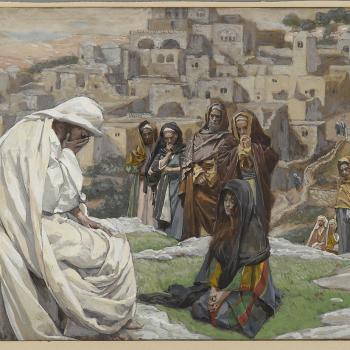

The temple and the two characters

Jesus’ story brings a Pharisee and a publican together in the temple. It’s an odd connection, a scandal, and Jesus’ audience knows it. The publican has no right to be in the temple. He’s a public sinner. Most of Jesus’ audience, public sinners also if for no other reason than not paying tithes, were under the same restriction. They don’t dare go to the temple, the place the community designates for receiving God’s mercy and favor. Neither should he. They take offense at the publican, but not at the Pharisee.

The Pharisee “took up his position,” a prominent one. Jesus focuses on the words he says. There are a lot of words. We see that he is an especially rigorous follower of the Law. He fasts twice a week instead of the acceptable once. He tithes his “whole income”; his generosity is exceptional. He’s a cut above the rest, whom he calls “greedy, dishonest, adulterous.” He despises the publican.

The publican’s words are few, but Jesus pays special attention to his posture and actions. He stands by the East Gate, barely visible to the Pharisee. He lowers his eyes, and beats his breast. His words are simple: “O God, be merciful to me, a sinner.”

You might say his actions and words are properly humble. But once you understand his situation, you can see something else. He’s not “supposed” to be there. He took a great risk, and he doesn’t want to be more offensive than necessary. Certainly he wants to avoid censure. So he cuts a low and reverent profile and stands far away from the holiest areas. We don’t know about his soul. Perhaps he’s humble, but he’s certainly frightened. I’m guessing Jesus’ audience would pick up on this latter state rather than any moral quality like humility.

‘Opening up New Possibilities: Challenging the Limits’

That heading is the title of Part Three in Herzog’s Parables as Subversive Speech. In this parable Jesus does challenge limits and open possibilities. Jesus’ listeners see the publican getting even more than he asked for in his daring venture into the Temple. He had labeled himself a sinner and asked for mercy, and he went home “justified.” Incidentally, asking for mercy does not single him out as especially humble. Mercy is what people, perhaps not including the Pharisee, generally went to the temple for.

We don’t know what sins were on the publican’s mind. Would he have thought his way of life as a hated money collector was sinful? Perhaps, like most others, he thought about the purity code. The story doesn’t tell us, and it doesn’t matter.

The sins of the Pharisee also don’t enter into the story. Indeed, he is a sinner, even a public sinner. His sinful participation in an oppressive system is obvious to everybody, only not generally recognized as sinful. But those sins don’t enter into this story. It’s religious, not economic or political, oppression that Jesus features in this story. The coming parables in Herzog’s Part Three will take up those other issues. They will inspire conversation about the quality of life for peasants and laborers and possibilities open to them. I’m nearly certain that the anger toward the publican that Jesus’ audience felt and their shock at the surprise ending left them ready for hashing things out. Whether anyone dared to follow the publican’s example and challenge the reigning religious story, Jesus, at least, planted a seed.