The crowd on Palm Sunday hailed Jesus as the new King David. Jesus twice (at least) laid to rest the idea that the Messiah would bring back the days of that famous king. Once it was in a provocative question: “David himself calls him [the Messiah] Lord; so how is he his son?” (Mark 12:37) Once it was by means of a parable, the subject of this post. Jesus disowns the popular conception of and hope for the Messiah. That, to skip all the details, is William Herzog’s conclusion after analyzing the Parable of the Unmerciful Servant in the Gospel of Matthew.

Of course, you can’t get there without the details. In fact, reading on my own about the servant who was forgiven but refused to forgive in turn, I never would have got there. I would have found only the exhortation to, as Matthew summarizes, “forgive my brother from my heart.” Herzog in Parables as Subversive Speech lets the social context in which Jesus lived throw light on the parable. This gets us behind Matthew’s interpretation to what Jesus’ listeners would have heard and, hence, what Jesus must have meant.

Previous posts in this series on William Herzog II’s Parables as Subversive Speech:

- William Herzog Reads Jesus’ Parables, Brings them Down to Earth

- Paulo Freire, the “Pedagogue of the Oppressed”: Is This a Good Fit for Jesus?

- Laborers in the Vineyard: A Reading that Doesn’t Blame the Victims

- The Parable of the Wicked Tenants and the Wickeder Landlord

- The Rich Man and Lazarus, or an Oppressor who Won’t be Taught

Matthew or Jesus

The effort to get behind what the Gospels say to the “real” Jesus is not so much in favor now as it has been, Herzog avows. But he engages in it anyway. It raises a serious question about the word of God. Do we believe Matthew or what detective work can say about Jesus or, somehow, both, even when the two are not the same?

I’m going with both, but not to the same degree of commitment. The Bible is the word of God coming to us through the skills and limitations of Christian authors. Detective work, even about Jesus, is just a work of human beings. That still leaves a question about what those early Christian writers were doing. Did a story about what Jesus did and said get changed, intentionally or not, in the human process that led to the Bible? And is God OK with that?

I addressed the issue in this early post. One of the good things that people do is write different kinds of literature. The Bible is a mixture of genres, including whole books, like Jonah, which read like historical fiction (or a tall tale in Jonah’s case). Matthew’s stories about Jesus also seem, on close inspection, to be partly true to history and partly made up. In the ancient world that was a common, well understood, and accepted practice. For Matthew it was a way to get a message across to his community. If Jesus’ message was different, that doesn’t mean Matthew’s is any less inspired than Christians have always thought.

Matthew and Jesus

Matthew makes the unmerciful servant story an inspired lesson about the need to forgive. Why, then, even try to figure out what else Jesus might have done? I think the answer is, because of the Incarnation. God entered into our history not just in ideas but as a person. As much as I appreciate what the Gospel writers and the Holy Spirit accomplished in the written word, I still want to get close to Jesus as he walked the paths of Galilee and Judea. I want to follow Jesus in my imagination with the peasants and even the scribes and Pharisees and learn from him. The scholarly “quest of the historical Jesus,” imperfect and provisional human work that it is, helps me do that.

The Parable of the Unmerciful Servant (Matthew 18:23b-34)

Matthew makes the Parable of the Unmerciful Servant part of Jesus’ answer to a question Peter raised: How often must I forgive my brother? That placement and the introduction, “The Kingdom of heaven is like….” may have been Matthew’s creativity working. Likewise the moral at the end about forgiving from the heart. Herzog sees these as external to the parable. The story in Jesus’ telling, then, would be the following, paraphrased and shortened a bit:

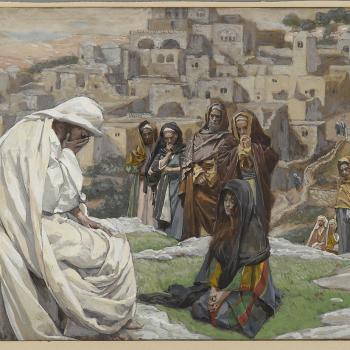

A king decided to settle accounts with his servants. One servant owed him ten thousand talents. Since had no way of paying it back, his king ordered him to be sold, along with his wife, children, and property. At that the servant fell down and did him homage. He said, “Be patient with me, and I will pay you back in full.” Moved with compassion, the ruler let him go and forgave him the debt.

When that servant left, he found a fellow servant who owed him a hundred denarii. He seized him and started to choke him, demanding, “Pay back what you owe.” Falling to his knees, his fellow servant begged him, “Be patient with me, and I will pay you back.” But he refused. Instead, he had him put in prison until he paid back the debt.

When his fellow servants saw what had happened, they were deeply disturbed. They reported the affair to their lord. The ruler summoned the servant and said, “You wicked servant! I forgave you your entire debt because you begged me to. Should you not have had pity on your fellow servant, as I had pity on you?”

Then in anger he handed him over to the torturers until he should pay back the whole debt.

The social context of the parable

This parable is a snapshot of elite life Palestine. That doesn’t mean Jesus is talking to rich folks. Peasants were well aware of the kind of life their social superiors led. They would have had no trouble supplying the background necessary to understand what’s going on. Background is what we lack. That’s where Herzog’s work is helpful.

We need to look at how the “other half” (far less than half!) lives. Where it concerns material comforts, their life is a bed of roses. The thorns, though, are the many pains it takes to stay in that bed. It’s a dangerous world. In a no-growth, zero-sum economy, anyone’s gain is someone else’s loss. That goes, crucially, for honor as well as money and possessions. It’s a world of cutthroat competition.

The parable’s king and all the servants in the story are upper echelon. They deal in lots of money. The ten thousand talents in the first scene is an unimaginably huge sum. I originally thought the servant was a pitiable creature. But he didn’t rack up such a debt (even if 10,000 is a later exaggeration) buying food for his poor family. He must have been rich to owe that much money. Probably he collected rents, fees, or taxes for his king and some extra for himself.

It seems he became rich enough that he could imagine challenging the ruler. So he starts spending much of what he owes on the gaudy show that was obligatory for the rank he aspires to. A miscalculation there, as the king decides to call in the debt unexpectedly. The servant’s plea for time to pay back the debt was sincere. Even if he lacked the money at the moment, he had the means to acquire it.

What was the master thinking?

The master’s offer to forgive the whole debt is harder to figure. Herzog gives us a plausible scenario, but not too plausible, as I see it. The meaning of the parable depends on the king making a choice kings don’t usually make.

First, this is a valuable servant. Herzog describes him: “cunning, shrewd, ruthless, merciless, calculating, loyal, and political.” These are qualities that a king needs in his bureaucracy. There must be a constant flow of money into the royal treasury. This servant must have a high place to handle so much money. He has connections, including people who owe him money.

The king’s threat to punish gets the servant to back down. That’s what the king needed. This servant is not likely to try such a maneuver again. But the king not only withdraws the punishment; he forgives the whole debt. Herzog imagines this move will secure even more loyalty from the servant, but more than that is going on in Jesus’ story. We need to look at what the chastened and newly loyal servant does next.

The unmerciful servant

Jesus’ story, uplifting until now, suddenly takes a turn for the worst. The servant, once brimming with ambition and confidence, is now seriously chastised. His many partners and underlings have heard all about it. He’s lost honor, and he needs to get it back. He attempts to do so by showing the world that he’s still a tough guy.

So he picks out one of his clients who owes him a hundred denarii. Compared to ten thousand or even a hundred talents, that’s a small amount. But it’s a rich person’s problem. A peasant would never see that much money at one time. We’re still in a world far removed from ordinary folk.

Acting tougher, perhaps, than he feels, the servant demands a settling of his loan to this middle-level bureaucrat. Herzog describes:

He will demonstrate to the vultures searching for signs of weakness that he is as strong as ever…. If he has to sacrifice one client to make his point, it is a price worth paying.

Unfortunately for him, he has miscalculated again.

Other servants in the bureaucracy and the king

It takes a lot of people to control a whole society. There are all the bureaucrats the king retains in his service plus parallel and sometimes competing bureaucracies of rich landowners and traders. Still, they’re a small part of the populace and they’re in a precarious position. The bureaucrats exist between the exploitation of the aristocrats and the hostility of peasants and artisans whom they exploit. Herzog says,

To survive, they needed to support one another. They could not treat one another as they would the vast population outside the bureaucracy.

The unmerciful servant breaks that rule. Now what will his underlings do? Their patron has been put down, and if he falls any lower, it’s bad news for them. On the other hand, he has struck in anger once; he might do it again. A likely option is for them to switch to another patron, who won’t be sad to see one fewer competitor. With his support they can go to the king and inform on their former patron. Or perhaps some among them are already informers whom the king pays to keep himself abreast of matters.

Now the king is in an uncomfortable position. His show of mercy was a failure. It only brought about more cruelty and insecurity among the people he depends on. He must respond. He was shamed into doing what he had set out not to do: hand the unmerciful servant over to torturers.

“What if the Messiah Came and Nothing Changed?”

This heading is the title of Herzog’s Chapter 8 in Parables as Subversive Speech. The king in Jesus’ parable shows some semblance to the Messiah that common folks were hoping for. He seems like a nice guy. He forgives debts.

Debt, in fact, was the great problem for the majority of people just barely making it in Palestine. Peasants took on debt in exchange for seed for planting and, with a good crop, paid it off along with taxes and other fees at harvest time. A poor crop threatened loss of land or, perhaps, family members to slavery. Artisans, like Jesus and his father, faced similar perils.

But it wasn’t supposed to be that way. Sabbaths saw rich and poor gathering to hear the Scriptures, and some of those texts severely castigated fat cats who “join field to field and house to house.” (Isaiah 5:8) Every seventh year, the Sabbatical Year, debts were to zero out. And every fiftieth year, the Jubilee Year, debt slaves were to gain back their freedom and the land they had lost. The messianic hope of the poor was for a king like David who would re-impose these long-ignored provisions of Scripture. Jesus, by some of his talk and actions, seemed to be filling that bill. And here Jesus tells a story of a king who forgives debts.

But, OH NO! Things go very wrong in this story, and in the end everything is the same as it was. The system is all-encompassing and overpowering. Even a king can’t change it. Herzog concludes Chapter 8:

In short, the parable proposes that neither the messianic hope nor the tradition of popular kingship can resolve the people’s dilemma. To reshape their world, the people of the land must look elsewhere. Just where is not the concern of this parable.