In the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus, Jesus, the pedagogue of the oppressed, features a pedagogy of the oppressor. And this pedagogy fails: the rich man doesn’t learn.

This post in a series on William Herzog’s Parables as Subversive Speech turns to his Chapter 7, “The Unbridgeable Chasm.”

Previous posts in the series:

- William Herzog Reads Jesus’ Parables, Brings them Down to Earth

- Paulo Freire, the “Pedagogue of the Oppressed”: Is This a Good Fit for Jesus?

- Laborers in the Vineyard: A Reading that Doesn’t Blame the Victims

- The Parable of the Wicked Tenants and the Wickeder Landlord

Why this parable?

Whatever else Jesus was – savior of souls, opener of the gates of heaven – he was also an advocate for raising the status and material condition of the poor. He was a social justice activist, not just a do-gooder. William Herzog calls Jesus a pedagogue of the poor. He sees in many of Jesus’ parables a kind of consciousness raising and empowering, to use today’s jargon. Jesus challenged the status quo.

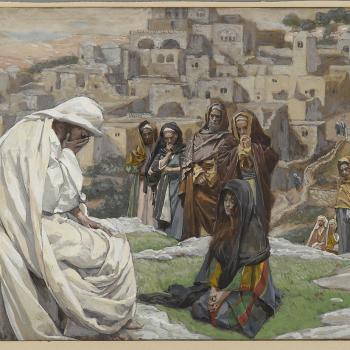

With that understanding, I was surprised to find The Rich Man and Lazarus among the parables that Herzog takes up. Here’s a rich man, flaunting his wealth to the world, dressed in expensive imported garments and feasting daily on the finest fare. And there’s Lazarus covered with sores, hoping only for someone to give him scraps from the rich man’s dining room floor. And nothing changes in their lives on earth, but the accounts balance out when they each die. Lazarus dwells in a blessed state in Abraham’s bosom, and the rich man burns in torment in the netherworld. It seems to teach exactly what a Christian today would expect. I should help those less fortunate than I, and if I don’t, I can expect to burn in hell. But if I’m miserable in this life, I can at least hope to be happy in the next. This parable seemed to be more comfort than challenge.

Reading a first-century story with 21st century eyes, however, there were some things I didn’t understand. But first, the parable, with some paraphrasing, from my New American Bible’s translation.

The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31)

There was a rich man who dressed in purple garments and fine linen and dined sumptuously each day. And lying at his door was a poor man named Lazarus, covered with sores. He would gladly have eaten his fill of the scraps that fell from the rich man’s table. Dogs even used to come and lick his sores.

When the poor man died, he was carried away by angels to the bosom of Abraham. The rich man also died and was buried. From the netherworld, where he was in torment, he raised his eyes and saw Abraham far off and Lazarus in his bosom. And he cried out, “Father Abraham, have pity on me. Send Lazarus to dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue. I am suffering torment in these flames.

Abraham replied, “My child, remember that you received what was good during your lifetime while Lazarus received what was bad. Now he is comforted here, and you are tormented. Besides, there’s a great chasm between us, preventing anyone from crossing from our side to yours or from your side to ours.”

The rich man said, “Then I beg you, father, send him to my father’s house. I have five brothers. Have him warn them, lest they too come to this place of torment.

But Abraham replied, “They have Moses and the prophets. Let them listen to them.

He said, “Oh no, father Abraham, but if someone from the dead goes to them, they will repent.”

Then Abraham said, “If they will not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded if someone should return from the dead.”

Understanding the rich and God’s favor

I said before there were things I didn’t understand. One was Jesus’ contemporaries’ expectations about the afterlife. They weren’t like ours. People then supposed that, if anyone was headed to heaven, or the Kingdom of God, a rich person was. Remember the disciples’ astonishment at Jesus’ saying about the rich man, the camel and the eye of a needle. “Who then can be saved?” they cried. (Matthew 19:25) Everyone “knew” that, if you were rich, you had the time and the means to put in place all the complicated requirements of the Scriptures’ purity code. If by chance you became impure, you could offer the assigned sacrifice in the Temple. And you could afford the Temple tithe. The temple and its priests were the conduit for God’s favor. Being rich meant you could get that.

On the other hand, if you were poor, you probably couldn’t follow the purity code adequately. If you became impure, you couldn’t afford the necessary sacrifice. You probably couldn’t even pay the tithe that you owed to the Temple. Herzog cites estimates of how much a peasant farmer owed in taxes, tithes, tolls, fees, and debt payments: between 28 and 40 percent of a year’s earnings. And the Temple was the only payee that didn’t threaten one’s life or livelihood for non-payment. So you paid everybody else, if you could; and if you couldn’t pay the Temple, the priests only labeled you a sinner. Winning God’s favor and help from above for a successful harvest, to say nothing of being “saved,” seemed impossible.

The fact that Lazarus, and not the rich man, ends up in Abraham’s bosom in Jesus’ story must have come as a shock to Jesus’ listeners.

The master and the servant

The second thing I didn’t understand concerns masters and servants. That stratification of Palestinian society comes through in the second half of Jesus’ parable.

Here’s the rich man, without a name. Call him Dives; it just means rich. He’s tormented by flames, and he’s thirsty. This isn’t hell; Dives could learn and maybe repent. There’s Lazarus, resting comfortably in Abraham’s bosom. Dives sees Lazarus and Abraham far off, and he makes this modest request:

Father Abraham, have pity on me. Send Lazarus to dip his finger in water and cool my tongue. I’m miserable in these flames.

Abraham reminds him of what he knows already: You lived a life of luxury, and Lazarus one of misery. Now you’re stuck. Besides, Lazarus can’t even get from our side to yours.

Then rich Dives pleads for Abraham to send Lazarus to warn his brothers. It seems that Dives isn’t all bad. He thinks about somebody at least. Perhaps he learned from his suffering. Herzog says he hasn’t learned what really matters.

Dives makes two requests of “father” Abraham. Notice the nature of the requests:

Send Lazarus to cool my tongue.

Send Lazarus to warn my brothers.

Dives assumes that the master-servant or master-slave relationship is just reality. Dives had servants in his earthly life. So Abraham must have servants to send to do his bidding, even in the afterlife. It’s an ideology of stratified reality stretching all the way from the underworld to the stars and God’s abode. By this the rich justify to the poor their unequal places in human society. It’s just the way things are. Dives and Lazarus are still unequal – in Dives’ eyes.

Abraham’s unsuccessful pedagogy of the oppressor

Dives has a chance to learn while in the netherworld, and Abraham tries to teach him. Patiently Abraham reminds Dives that his brothers already have all they need. They have the Scriptures. Dives thinks that’s not enough: “Oh no, father Abraham, but if someone from the dead goes to them, they will repent.” Abraham’s final answer:

If they will not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded if someone should return from the dead.

How final is this answer? If I got a visit from a dead person, I might find that more convincing than simply reading the Scriptures. But Abraham knows better. Scripture counts for more than any sign from the dead. Scripture already contains whatever message a dead person might bring.

The problem is that Dives and his brothers have the Scriptures, but not the whole Scriptures. If they are typical of Judah’s elite, they follow faithfully the requirements that seem important to them. These would be the rules concerning holiness and purity, rules that separate the insiders from the outsiders. Without the Scriptures’ prophetic strain that lifts up the poor, the oppressed, the outsiders, these rules condemn the likes of Lazarus and most of the people listening to Jesus parable. If you asked Dives what advice Lazarus should give to his brothers, it would be simply to double down on the same rules. He has proved that, even in his torment, he still regards Lazarus as only a servant, an outsider. Abraham is right. The brothers wouldn’t change any more than Dives has.

The problem with money (sometimes) is money.

It’s no sin to be rich. So goes the platitude. Some interpreters insist that Jesus’ parable does not condemn the rich man’s wealth. Nor does it exalt poor Lazarus’ poverty as the reason for his blessed afterlife. Abraham, however, disagrees. He doesn’t refer to any other quality but wealth or lack of it to explain Dives’ and Lazarus’ different after-death situations:

[Y]ou received what was good during your lifetime while Lazarus received what was bad. Now he is comforted here, and you are tormented.

Does what the parable says about riches relate to us today, who have an economy very different from that of Jesus’ time. The first-century Mediterranean world had a zero-growth economy or close to it. When someone became rich, someone else became poorer. This happened, for the most part through loaning to subsistence farmers and taking their lands when they couldn’t pay. And it was perfectly legal – unless you count the Scriptures’ requirements of debt forgiveness and return of lost lands. Unless you take seriously the prophets’ option for the poor. (See this post on debt forgiveness.)

In the first-century world, the economic pie as a whole was not growing. But we live in an era of growth. There is no inevitable connection between one person’s wealth and another’s poverty. So Does Abraham’s lesson apply to us?

A lesson from Covid

Since the end of World War II it’s been a truism that economic growth would solve poverty and “a rising tide lifts all boats.” But truisms aren’t always true, or true forever. Up to the 1970’s rich and poor gained about equally, on average. Since then the wealth of the already wealthy skyrocketed while the middle class and the poor gained hardly at all.

Besides, economies don’t always grow; sometimes they shrink. During the Covid years, the superrich, again on average, gained enormously while many others lost jobs and homes. I like to say that in this period the nation’s 700 billionaires increased their wealth by about enough to pay for President Biden’s entire “Build Back Better” program. But, of course, they weren’t going to pay for it. Instead they trashed Biden’s program as too expensive and clung tightly to their low tax rates and loopholes. It’s hard, after all, not to see the parallel between them and the wealthy in Jesus’ world, who systematically extracted wealth from the poor.

It’s no sin to be richer than average, but it may be a sin to be a billionaire.

Peasants respond to Jesus’ parable.

William Herzog thinks that, when Jesus talks, a key to what he means is how his listeners respond. He knows his people and how they think. His message won’t be over their heads as if he’s talking to somebody else, say, us in the 21st century.

Herzog also believes that Jesus operates like a pedagogue of the oppressed. He doesn’t just tell peasant farmers what to think but lets them think for themselves. That means he has to work against the ways of thinking that oppressed peoples absorb or have drummed into them by their oppressors.

One of these false ideologies Herzog calls “blame the victim.” Whatever is going wrong in poor people’s lives, it’s their own fault. They aren’t pure enough to deserve God’s favor. Of course, it’s the oppressors who deprive the poor of the means to achieve that brand of purity.

The rich man in the parable is the epitome of purity as he and the elite of Judah style it; and Lazarus is about the opposite. But Lazarus is in Abraham’s bosom, and Dives is in torment. Along with the shock it delivers, that is sure to get poor people thinking. As Herzog imagines it near the end of Chapter 7:

The reversal of their expected states undermined not simply the hearers’ view of the afterlife but, more important, their assumption … that social class was an indicator of divine blessing or honorable status. Once this connection had been broken, the assorted rural poor of Galilee or Judaea who heard the parable could inquire into reasons for their misery that were much closer to home.

And:

If scribes were wrong about this matter, could they be trusted to interpret the Torah in other matters?

No wonder Jesus made enemies – enough to send him to a cross.

Note: I’m working with an online version of Parables as Subversive Speech so I can’t make citations with page numbers.