SAINT APRIL

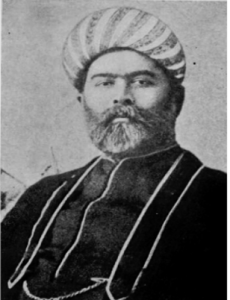

It was just around the time that Johnston was studying for his Sanskrit examinations when he wrote “Sanskrit Study In The West.”[1] It is also possible that he met Harvard Sanskritist, Charles Rockwell Lanman.[2] Given Johnston’s theory of language, and the use of the term “Mussulmani-Bengali,” it is likely that he also discussed the theory of language with the Nawab’s private secretary, Khondkar Fazl Rubbee. A man of “exemplary fortitude,” Rubbee was a man well-regarded by his peers.[3] The thirty-first in descent from Abu Bakr, Rubbee lived in Sha Rostum Monastery, in the village of Salar near Kandi. Sha Rostum, his direct ancestor, was the first of his family to arrive in India; a line which flourished in Bengal. With each successive Nawab, Rubbee’s ancestors accumulated land and titles, such as his own, “Khondkar,” which meant instructor or teacher.[4] Aside from the references made in his articles about the Nawab, it is unclear what opinion Johnston and Rubbee had of one another. Though the impression seems favorable, they did not share the same opinion regarding the history of Bengali Muslims.

Dewan Khondkar Fazl Rubbee, Khan Bhadur.[5]

In 1869 Rubbee traveled to London with Nawab Mansur Ali Khan. While he was in England, the British Government initiated the first Census in colonial India in 1872. The question of race, religion and castes were introduced without any consideration of its impact on the life of the Indian people. This was an important development, as it set a precedent for foreign powers in defining the terms for the religiosity of a subjugated people, and, to a large extent, set the parameters for heterodoxy and orthodoxy. The ramifications for this would ultimately lead to a religious cleavage between majority Hindus and minority Muslims.[6] This metric would be used elsewhere in the British Empire, and consequently create sharply defined ideologies. This would be an issue which Rubbee would take up when he returned to Murshidabad in 1874. The 1872 Census concluded that “the foreign element amongst the Muhammedans of East Bengal is very small,” and suggested that the Muslims of Bengal were of the same racial extraction as that of the Hindus. Rubbee, a learned scholar, disagreed with this claim, and was “not a little angry with Sir W.W. Hunter for adhering to this theory.” He argued that the Bengali Muslims were not the descendants of the Hindu community, rather, Bengali Muslims had owed their origins to immigrants from abroad, and other parts of India.[7] Rubbee would commence work on proving his etiological rebuttal, which would be published in Persian in 1893 under the title, Haqiqat-i-Musalman-i-Ban (1893,) and in English in 1895 under the title, The Origin of the Musalmans of Bengal (1895.)[8] In it, Rubbee writes:

It will thus appear that the supposition of Sir W. W. Hunter with regard to the Musalmans of Bengal is quite baseless and unreliable. Such being the case it can safely, and without any fear of contradiction, be asserted that the ancestors of the present Musalmans of this country were certainly those Musalmans who came here from foreign parts during the rule of the former sovereigns, and that the present generation of Musalmans are the offspring of that dominant race who remained masters of the land for 502 years.[9]

Johnston, however, would state:

Turning from the philology to the ethnography of Lower Bengal, as exemplified by the District of Murshidabad, it should be noted, at the outset, that the Census Division of the population into Hindus, Mussulmans and aborigines, has no ethnical value whatever. The employment of general terms like “Hindu” in ethnography is quite illusory, and ought to be avoided; like whitewash over a mosaic, these generalizations hide real differences which are often of the first importance. The mass of rural Mussulmans in Lower Bengal are not at all the descendants of Mussulman invaders, whether Persian of Mughal, but converts from one or other of the forms of religion classed as “Hinduism.” Ethnically, they differ in nothing from the masses of “Hindus” about them.[10]

Though the Muslim population of Bengal out-numbered their Hindu brothers, theirs was a syncretic tradition, often not easily distinguishable from Hinduism, which, itself, was fluid in the region. In 1883, not long after H.S. Olcott first met the Nawab of Murshidabad, a study was published which revealed that many of the Muslims in the rural parts of the Bengal Presidency could not even perform their namaz (prayers) in Arabic.[11] In A History Of Murshidabad District (1902,) J. H.T. Walsh writes:

The festival of the Mohurram is naturally more respected by the Shiahs than by the Sunnis, and, while the former keep the whole period of ten days mourning, the Sunnis regard the tenth day only as sacred, and that only as the anniversary of the creation of the world. Disbelieving in Ali as the first Kalifah, the Sunnis would not be likely to mourn the death of his son. Some days before the Mohurram small bamboo and mat huts are erected by the wayside and * near the entrance of the palace gates in Murshidabad. In these are placed jars filled with water, that none may suffer from thirst as did the martyr Husain. Many of the Shiah mosques are draped with black, and tazzias are carried in procession through the streets. This mourning gives rise to great excitement and strong feeling among its votaries, and has, unfortunately, led to race quarrels and bloodshed. The mourners, as they go along, wail and cry for the dead martyrs and curse their persecutors. The tenth day is called the “Roz-i-Qatl,” and on this day the tazzias are carried in procession, with deafening noise of voices and instruments, to a mosque at Amaniganj, about two miles from Murshidabad city. Elephants and horses, all in their finest trappings, accompany the procession. At the Amaniganj mosque prayers are read and the tazzias are then thrown into the river.[12]

The festival which followed Muharram, the “Beret Festival,” was a fine example of the aforementioned syncretic folk tradition of the Presidency. Bengali Muslims venerated pirs (saints/holy men) in a practice unique to India.[13] Each pir, as a rule, had their own durgah (shrine.) According to the Sikandar Nama, there was once a Muslim pir named Khwaja Khizr (or Pir Badr,) who presided over the well of immortality, and directed Alexander the Great in his quest for “the blessed waters.” One legend claimed that Khwaja Khizr belonged to the family of be Noah, whom rural Muslims of Murshidabad regarded as a water deity in connection with the flood. Khwaja Khizr was said to ride a fish; hence the image of the fish was painted over the doors of both Hindus and Muslims in Bengal. Khwaja Khizr was said to dwell in the rivers and seas, protecting people against shipwreck and drowning, but supplications were made to him during times of misfortune and of happiness. Bengali Muslims prayed to Khwaja Khizr at the first shaving of a boy, and a small boat was launched in a river in his honor. This same rite was performed at the close of the rainy season during the Beret Festival (Raft Festival.) This festival was held on the last Thursday night of the Hindu month of Bhadrapada, which, during Johnston’s time in India, fell on September 19, 1889. That the festivities should be connected with a Hindu month owed to the curious co-ownership of Khwâja Khizr between Muslims and Hindus, the latter regarding the pir as a water god named Raja Kidar. The Beret Festival marked the “end of the rains.” Nearly everyone made, or purchased, a little boat of plantain or bamboo which held a sweetmeat or two, and a small oil diya lamp. Thousands of little ships, each with its offering and burning lamp, floated down the Bhagirathi, a tête “rendered more picturesque,” it was said, “by the unusual presence of the women, who [were] allowed out of doors for the occasion.”

The Nawab made the Beret Festival an occasion for hosting the Europeans to dinner. The Nawab’s own raft, a 100 cubits square, was made from plantain trees and bamboo, and covered with dirt. On this was erected a small fortress, carrying all kinds of fireworks, “[a] mass of little, twinkling lights.” When the vessel sailed past the palace, a signal was given and the grand display of fireworks was launched, “their reflection on the water producing a most beautiful effect.” When the spectacle concluded, the “half-lighted and smoking skeleton,” of a boat, faded into the darkness with its “less ambitious sisters.”[14] John Gerald Ritchie, the Collector of Murshidabad, writes: “There was a good deal of tinsel bravery about Moorshedabad—elephants and camels and carriages and a band. The Nawab used to give gorgeous entertainments and was much liked by the European community.”[15] This era of syncretism was coming to an end by the time that the Johnstons were in India, a culmination of so-called reforms which had been underway since the British first set foot on the Sub-Continent.

Islamisation in Bengal was spear-headed by Muslim reform societies like Faraizi, Taaiyyuni, Ahl-i-Hadith, etc., which sought to remove un-Islamic ways of life.[16] It was claimed that the followers of Saiyid Ahmad Bareilvi, whom the British called Wahabis, played a decisive role in organising the 1857 uprising. The jihad (holy war) waged by Bareilvi and his followers, however, was only a militant manifestation of a growing movement aimed at “cleansing Islam” in India of perceived heterodox practices. Though the movement was identified by British as one in the same as the Wahabis of the Arabian peninsula, and referred to the belligerents as jihadis, Bareilvi’s followers preferred to be called Ahle Hadis (men of Prophet’s tradition.)[17] Bareilvi was a follower of the more tolerant Hanafi school of jurisprudence (and initiate of the Naqshbandi Sufi.) The founder of Wahhabism, the eighteenth-century scholar, Abd al-Wahhab, belonged to the puritanical Hanbali school of Islamic thought (anti-Shia, anti-Sufi, etc.) His philosophy was much indebted to the fourteenth-century jurist, Ibn Taymiyya, an idealogue who popularized the notion of militant jihad.[18] Just as the Muslims made little distinction during the Crimean War between Christians, neither did the Christians. Most of the Anglophone world saw the uprising of 1857 subcontinent though it were a Jihad waged by global Islam against global Christianity.[19]

Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Government of India Act 1858 led to the British Crown assuming direct control of India from the EIC and establishing the British Raj. The interests of Britain were now linked closer with those of Turkey, and Abdul Aziz, the Ottoman sultan. They were now both rulers of Muslim peoples, and that both (along with the Muslims of Central Asia,) were threatened by Russian expansion. With the Islamic Mughal government gone, the British disseminated propaganda in India, admonishing their Muslim subjects to be loyal to the British Government as it was allied with the caliph. Englishmen even participated in forming Muslim Leagues in the hope of blocking Russian expansion in Central Asia.[20] It was not long after when the Muslim elites of Murshidabad became embroiled in the controversy regarding their origin. The British Government’s 1872 census stated:

These tribes, swept down the Gangetic valley by the advancing wave of Aryan immigration, were brought to bay, as it were, in the sea-girt province of Bengal. There they were partially incorporated into the Hindu system, or became the slaves of their Aran conquerors. It would be as great a mistake to suppose that the Aryan invaders exterminated or drove out all the aboriginal inhabitants of Bengal as it would be to suppose that the Saxons exterminated all the ancient Britons who did not flee into Wales. Indeed, so far from displacing the indigenous children of the soil, the Aryan element, as we know, was only able to hold its own by frequent importations of fresh blood from Upper India. In order to exist at all, in fact, Hinduism in Bengal had to assume a baser form than elsewhere. It was compelled to assimilate and adopt the barbarous practices and superstitions of those whom it sought to embrace within its fold. Its Pantheon became crowded with elephant-gods and bloodthirsty goddesses, of whom the primitive Aryans knew nothing. The absorption, however, of the aboriginal in the Aryan element was far from being complete. The indigenous tribes, though possibly admitted into the social and religious system of the Hindus, found themselves at the very bottom of the scale. Under an exclusive caste system, they were merely the despised serfs of a victorious and superior race. They were the hewers of wood and drawers of water, for a set of masters in whose eyes they were unclean and altogether abominable. Such was the condition of these tribes, we may suppose, at the time of the Mahommedan invasion. To such people that invasion would not be altogether unwelcome. In the eye of Islam, at any rate, all men are equal. We can easily understand, therefore, that when once the Mahommedan conquest was extended to Bengal, large numbers of these miserable helots would hasten to profess the religion of their conquerors. They thus not only escaped from their ignoble position under the Hindu system, but they might aspire to be the social equals of their late masters. A strong proof that this is in reality the true explanation of the large number of Mahommedans now found in Lower Bengal is afforded by the close resemblance between them and their fellow-countrymen who still form the low castes among the Hindus. That both were originally of the same race seems sufficiently clear, not only from comparisons of physical characteristics, but from the similarity of their language, manners, and customs. The Bengali Musalman is still in many respects a Hindu. Caste distinctions, one of the main objects of which would seem to be to prescribe the limits of the jus connubii, are to a certain extent as prevalent and as fully recognized among the Mahommedans of Bengal as among Hindus.[21]

The question of Islamic solidarity, and the British conception of it, was no doubt on the minds of the community. The rise of Pan-Islamism and the Mahdist wars in the summer of 1882 were topics that could not be avoided. It is probably not a coincidence that the Nawab of Murshidabad made is Rs. 400 donation to the Branch Library of the Berhampore T.S. (and accompanying letter which pledged his support to the objects of the Society,) at the same time the Muslim/Christian conflict erupted in Alexandria (1882.)[22] While Western academics were defining the boundaries of other religions, Pan-Islamists were making their own definitions in India. Al-Afghani arrived in Calcutta in November 1882, and his talks would prove very influential to the Muslim elite of Bengal with his Pan-Islamic and anti-West ideas.[23] By 1883, many Muslim theologians renewed their emphasis on the process of Islamization, which would ultimately be the death knell of the vibrant syncretic folk traditions which flourished in the region.[24] No doubt, al-Afghani had left an enduring impression.[25] A “misunderstanding had arisen,” it was said, “not between Hindus and Muslims, but between the different schools of Islam.”[26]

Elsewhere in the Islamic world, the Khedive of Egypt had embarked on campaign to eradicate slavery in Egypt under the sphere of operations organized in Khartoum (Legitimate trade was accompanied by slave-raiding, and these merchants were the virtual rulers of the districts in which they traded.) The Khedive appointed the British explorer, Sir Samuel Baker, (whom the Johnston’s met on the Arcadia) to lead an expedition to facilitate a trade route to the Upper Nile and to suppress the slave trade in Sudan. Besides the practical difficulties of enforcing such an edict, slavery was an institution which was halal (permitted) in Islam, and the appointment of a Christian to suppress said institution caused resentment among the peoples of Sudan, as slavery was a major source of income for them at the time.[27] The growing resentment of his people toward outside influences was not the only problem which the Khedive faced. His modernization projects had placed Egypt in debt. The British swept in to pay the debt in return for a controlling share of the Suez Canal. The British effectively became the administrators of Egyptian fiscal affairs. In 1873 the British government established a joint debt commission with the other European shareholders, the French.[28]

It was at this time that a joint-group of English and German businessmen had a new plan for settling Jews in the Ottoman Empire. These businessmen proposed to the Ottoman Sultan a railway from Smyrna to Baghdad, along the length of which they would establish communities of Jewish workers. In November 1881 the Ottoman Council of Ministers considered the question, and they announced that “[Jewish] immigrants will be able to settle as scattered groups throughout Turkey, excluding Palestine,” adding that they “must submit to all the laws of the Empire and become Ottoman subjects.”[29] Doubts to the Sultan’s commitment to Islam began to arise. In 1881, the Ottoman Empire was in the embarrassing position of having European interference in its internal affairs, as various foreign powers assumed control of its Public Debt.[30] Europeans were encroaching on the Islamic world. Besides the loss of land from the Russo-Turkish War, the Europeans were carving up North Africa. The French, by 1881, had taken control of Tunisia.[31]

A broad movement of Islamic reform was taking hold at this time which Europeans compared to Pan-Slavism, and subsequently given the moniker of “Pan-Islamism.”[32] One such Pan-Islamic movement had developed in Sudan as a response to the perceived heterodox practices of the Egyptian Khedive and his un-Islamic policies. A spiritual leader named Muhammad Ahmad declared himself the prophesied Mahdi (a messianic figure who features in Islamic eschatology believed to herald the end of times and cleanse the world of injustice and sin) and declared a Jihad against the Ottoman/Khedivate oppressors and their allies.[33] The Mahdi and his followers (known self-referentially as Sufis and later Ansā) whom the British called Mahdists began their guerilla campaign in November 1881, the first step in the establishment of a vast Islamic State which would stretch from the Red Sea to Central Africa.[34]

The Muslim philosopher, Sayyid Jamaluddin al-Afghani, one of the earliest and most influential leaders of Pan-Islamism, (who claimed to be the tutor of the Mahdi,) was touring the British Empire and critiquing the West.[35] When asked if the Mahdi could be removed by force, stated: “The best method of crushing a religious rising, to my mind, is to allow co-religionists to do it.” When asked what the word Mahdi conveyed to Muslims, al-Afghani stated: “Mahommedans believe, according to Islamic tradition, that an end of time there will appear a Mahdi, who will be recognized by certain indications, and his mission is to exalt Islam throughout the world.”[36] With his authority being challenged, the Sultan could ill afford to lose the support of the Ummah by “losing” Palestine to the Jews.

The decaying Ottoman Empire had paid little attention to malaria-ridden province of Palestine in the past. It was such a low priority in fact that it did not even have the status of an independent colony, rather, it was considered the southern part of the Damascus district.[37] In the closing months of 1881, however, the Sultan began a renovation of the sacred Mosque of Jerusalem known as The Dome of the Rock, (and which the British press erroneously reported as a restoration of “Solomon’s Temple.”)[38] The Mosque was built over the great stone that was the Sacrificial Altar of the Second Jewish Temple, and allegedly “the scene of Isaac’s intended sacrifice.” After the Romans destroyed the Temple, they built their own Temple to Jupiter. When the Caliph Umar conquered Jerusalem in 638 C.E. a mosque was built on the spot. It held a special reverence for Muslims, as they believed that this was the place where the Prophet Muhammed “ascended to heaven.”[39] Pan-Islamism had become a great menace to the British Empire as a result of their coldness toward the Ottoman Sultan since 1878. [40]

In 1881, an Egyptian army officer, Ahmed ‘Urabi (then known in English as Arabi Pasha), mutinied and initiated a coup against Tewfik Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan, because of grievances over disparities in pay between Egyptians and Europeans, as well as other concerns. In January 1882 the British and French governments sent a “Joint Note” to the Egyptian government, declaring their recognition of the Khedive’s authority. On May 20, British and French warships arrived off the coast of Alexandria, and on June 11 anti-Christian riots broke out in Alexandria resulting in the death of that 50 Europeans. The French fleet was recalled to France and on 11 July the British navy began its Bombardment of Alexandria. Egypt became a British protectorate in 1882.[41] ‘Urabi was captured, and sent to Ceylon in exile, where Noguchi would meet him en route to the 1888 Theosophical Convention. British papers noted that the British occupation of Egypt seemed to “have aroused all the spirit of prophecy which [had] lain dormant for some time.” The signs and wonders of the moment appeared to indicate the “re-establishment of the Jews in Palestine, the re-building of the Temple of Solomon, and the finding of the Ark of the Covenant.”[42]

The question of Islamic solidarity, and the British conception of it, was no doubt on the minds of the community. The rise of Pan-Islamism and the Mahdist wars in the summer of 1882 were topics that could not be avoided. It was in this context that we find Nobin K. Banerjee’s encouraging update of the Berhampore Branch to the editors of The Theosophist. The Nawab of Murshidabad had donated Rs. 400 to the Library of the Branch Society. It was accompanied by a letter in which the Nawab stated that he fully sympathized with the objects of the Society, and that it was “highly desirable that every effort should be made for the regeneration of India, and the revival of its ancient glory.”[43] The news was worthy of note, for as Bannerjee said, the Nawab was “a Mahomedan Prince” while he (Bannerjee) was a Hindu Brahmin by birth. “It shows how much good can be affected,” writes Bannerjee, “if all India understands and accepts the principles of Theosophy in our efforts towards our regeneration and mutual help, even in ordinary concerns of their life, instead of giving way to animosity and antipathy based on ignorance and bigotry.”[44]

The timing of the Nawab’s praise for the T.S.’s mission of religious pluralism, came just days before the Anti-Christian riots of Alexandria, Egypt, on June 11, 1882. By July 1882 the Anglo-Egyptian War would commence. The result was the British occupation of Egypt. In 1881 an Islamic revivalist movement had developed in response to the perceived heterodox practices of the Khedive and his un-Islamic policies. A spiritual leader named Muhammad Ahmad declared himself the prophesied Mahdi (a messianic figure who features in Islamic eschatology believed to herald the end of times and cleanse the world of injustice and sin) and declared a Jihad against the Ottoman/Khedivate oppressors and their allies.[45]

By 1882 the theory of “Aryan supremacy” was firmly-rooted in academic institutions.[46] Though it initially began as a linguistic term, it was already being used to designate race. Since the peoples who spoke “Aryan” languages looked noticeably different, it was suggested that there were different “branches” of the “Aryan” racial family. Johnston’s Sanskrit teacher, Robert Atkinson stated at the time: “[The] Indo-Germanic family constituted the chief seats of a peculiar race, and whose characteristics might be briefly stated as white, red, and blue in skin, hair, and eyes respectively.”[47] At the same time, the French Orientalist, Ernest Renan was making a claim for the “Aryanation” of Christianity, divorcing the tradition from its “Semitic” origin. In Marc-Aurèle et la Fin du Monde Antique, Renan writes: “Religions are mighty by reason of the people that adopt them. Islamism has been useful or deleterious according to the races that have accepted it.”[48] The “racial” aspect of Islam was also going through a change of identity. With the rise of Pan-Islamism came the change in the image of Muslims spear-headed by Western scholars. Whereas in past centuries Muslims were depicted as rich, indulgent, Ottoman pashas, the “quintessential Mohammedan” was now seen as a violent, zealous, camel-riding, Arab nomad. Despite the total population of the Islamic world outside of the Arab population being an overwhelming majority of the religion’s practitioners, they were not regarded as representatives of Islam’s essential character.[49] While Western academics were defining the boundaries of other religions, Pan-Islamists were making their own definitions in India. Al-Afghani arrived in Calcutta in November 1882, and his talks would prove very influential to the Muslim elite of Bengal with his Pan-Islamic and anti-West ideas.[50]

In June 1887, at the Nawab’s request, Olcott delivered a lecture on Islam in the Palace.[51] Following the lecture, Rubbee joined the Theosophical Society.[52] The appeal, perhaps, was the harmonizing role which the Society could play. For example, in early 1888, according to Kali Prasanna Mukerji, thousands of Muslims assembled in Berhampore to participate in a discussion on some articles of faith in dispute. On the one side there were Shias and Sunnis, while on the other side there were the Wahabis. Learned Muslims came from Peswar, Delhi, Jounpur, and the like, came to offer their commentary. Mukherji noted that it was a “fact not a little significant of the progress of brotherly feeling throughout India that the umpires chosen by both parties are all of them Hindus.” It was the first time in the history of India, according to Mukherji, that Hindus were chosen as “umpires,” by Hindus.[53] Conflicts between the religious communities would become more frequent. This was not just external strife, but internal. Johnston writes:

During the intervening years there have been periods of bitter feeling, of violent outbreaks and vigorous repressions […] Violent feuds between Hindus and Mohammedans, inflamed by the desecration of temples and mosques. This has suggested large possibilities of anarchy and civil strife, if the peace-compelling arm of England were withdrawn. It is worth noting that these feuds come rather from discordant creeds than from difference of race. Of the fifty million Mohammedans in India, not one in a hundred represents the invaders who came through the Western passes in the armies of Mahmud of Ghazni, Baber, and Nadir Shah. The overwhelming majority are converts from Hinduism, identical in blood with their Hindu neighbors against whom they wage these bitter feuds. The motive for conversion has been social rather than theological, a passionate escape from the compartmented oppression of the Hindu system of caste, which confers high privileges on the Brahmans and bears so harshly on the lower castes. So that there is no real race cleavage behind these sectarian feuds; it is a mental, not an ethnical discord. But this discord is sufficiently threatening to inspire in the minds of the native politicians, Hindu and Mohammedan alike.[54]

Not long after his Sanskrit Examination, Johnston would experience, first-hand, the syncretism of Islam in Murshidabad. While Orangemen like his father were violently antagonizing Catholics in Ireland on St. Patrick’s Day, the people of Murshidabad, and their various faiths, were having something of an inter-religious festivity.[55] March 18, 1889, marked the beginning of Doljatra, or the “Swinging Festival” which, in West Bengal, was something of a spiritual-creole of the festival of Holi that was celebrated in the Upper Provinces. It was a celebration when offerings were made to the gods on the thirtieth solar Phálguna, or first of Chaitra; the fifteenth day, light-half, or full moon of Phálguna. In ancient times, when India was governed by native princes, and Hindu institutions were in full strength, a series of connected festivities spanned a period of several weeks called the Vasantotsava, or the feast of Vasanta (Spring) and Love. In those times, the Vasanta Panchami (the fifth of the light-half of Mágha) was regarded as the beginning of Spring, and was observed by “lustral and purificatory rites.” Over time the festival of Holi supplanted the initiatory Vasanta Panchamí, and though traces of the original purpose of the festival, “Love and Spring,” were still observable, they were largely deposed from the rites over which they once presided. Newer mythological creations were invented to account for the origin of the celebration. In other Provinces, an effigy of Holika, an asuri (demoness) and “devourer of little children,” was committed to the flames of a bonfire.

In Bengal, the focus of veneration was the young Krishna. Before sunrise on the morning of Doljatra, an image of Krishna was consecrated and sprinkled with a red powder known as phalgo made from the dried root of Amba Haldi (Curcuma Zerumbet.) Krishna was then carried to a swing which had previously been set up, and placed in the seat. As soon as the sun rose, it was set gently in motion for a few turns. This act was repeated at noon, and again at sunset. During the day, the members of the family and their visitors amused themselves by scattering handfuls of Phalgo over one another, or by sprinkling each other with rose-water. A celebration of “licentious mirth,” analogous to April Fool’s Day, followed for several days. People ventured into the streets,” singing and dancing, annoying people with pranks, shouting coarse witticism and vulgar abuse, and scattering phalgo over one another. While April Fool’s Day was “confined to the lower class of people,” in the West, in Bengal, Doljatra was celebrated by Hindus of every class, and even some Muslims. “It is doubtful,” wrote one observer, “if the Mahomedan of Lower Bengal really remembers his religion to be different from that of the Hindu.” Even the late Siraj-ud-Daulah, was quite fond of making “Holi Fools.”[56] There is evidence that, in Murshidabad at least, the festivity took on a Western element, celebrating “Saint April’s Day” on the first of April.[57]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Johnston, Charles. “Sanskrit Study in the West.” The Theosophist. Vol. X., No. 114. (March 1889): 337-344; Johnston, Charles. “Sanskrit Study in the West.” The Theosophist. Vol. X., No. 116. (May 1889): 492-496.

[2] See Lanman Bio Below.

[3] “The Nawab made a sign to the Secretary […]” [Johnston, Charles. “A Nawab’s Jewels.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) August 30, 1891]; “At the door beneath the grand staircase we were met by his highness’ private secretary. He was a really magnificent oriental, six feet high, like a bronzed eagle. He wore yellow satin, and a turban like the sun.” [Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March, 1899): 309-319]; “The Nawab’s secretary received us, like a Persian god, in a lower hall decked with tiger skins and Afghan weapons. There were also little Italian goddesses of white marble, which drew the eye of Gilber Sahib.” [Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly Vol. 108, No. 4. (December, 1911): 797-804.]

[4] Majumdar, Purna Chundra. The Musnud Of Murshidabad (1704-1904): Being A Synopsis Of The History Of Murshidabad For The Last Two Centuries. Saroda Ray. Murshidabad, India. (1905): 265-266.

[5] Majumdar, Purna Chundra. The Musnud Of Murshidabad (1704-1904): Being A Synopsis Of The History Of Murshidabad For The Last Two Centuries. Saroda Ray. Murshidabad, India. (1905): 266.

[6] Bhagat, R.B. “Role of Census in Racial and Ethnic Construction: US, British and Indian Censuses.” Economic and Political Weekly. Vol. XXXVIII, No. 8 (February 22-28, 2003): 686–391.

[7] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts And Consciousness Of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June, 1995): 16- 37; “Critical Notes: The Origins Of The Musulman’s Of Bengal.” The Calcutta Review. Vol. CII, No. 203. (January, 1896): viii-x; Rubbee, Khondkar Fuzli. The Origin Of The Musalmans Of Bengal. Thacker, Spink And Co. Calcutta, India (1895.)

[8] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts And Consciousness Of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June, 1995): 16- 37.

Rubbee would publish an English translation, The Origin of the Musalmans of Bengal, in 1895 see Rubbee, Khondkar Fuzli. The Origin Of The Musalmans Of Bengal. Thacker, Spink And Co. Calcutta, India (1895.)

[9] Rubbee, Khondkar Fuzli. The Origin Of The Musalmans Of Bengal. Thacker, Spink And Co. Calcutta, India (1895): 53.

[10] Johnston, Charles. “Bengali Philology And Ethnography.” The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review And Oriental And Colonial Record. Vol. Vol. IV., No. 7. (July, 1892): 110-123.

[11] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume II. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1900): 418-419; De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts And Consciousness Of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June, 1995): 16- 37.

[12] Walsh, J. H. Tull. A History Of Murshidabad District (Bengal): With Biographies Of Some Of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 67.

[13] Hunter, W. W. The Imperial Gazetteer Of India Vol. X. Trübner & Co. London, England (1886): 20-39; Crooke, William. The Popular Religion And Folklore Of Northern India. Archibald Constable & Co. Westminster, England. (1896): 47-48; Walsh, J.H. Tull. A History Of Murshidabad District (Bengal) : With Biographies Of Some Of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 63-64.

[14] Hunter, W. W. The Imperial Gazetteer Of India Vol. X. Trübner & Co. London, England (1886): 20-39; Crooke, William. The Popular Religion And Folklore Of Northern India. Archibald Constable & Co. Westminster, England. (1896): 47-48; Walsh, J.H. Tull. A History Of Murshidabad District (Bengal) : With Biographies Of Some Of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 63-64.

[15] Ritchie, John Gerald. The Ritchies In India: Extracts From The Correspondence Of William Ritchie, 1817-1862. J. Murray. London, England. (1920): 368.

[16] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts And Consciousness Of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June, 1995): 16- 37.

[17] Khan, Iqtidar Alam. “The Wahabis in the 1857 Revolt: A Brief Reappraisal of Their Role.” Social Scientist. Vol. XLI, No. 5/6 (May-June 2013): 15-23.

[18] Allen, Charles. “The Hidden Roots of Wahhabism in British India.” World Policy Journal. Vol. XXII, No. 2 (Summer 2005): 87-93.

[19] Malik, S.D. “‘Mutiny’ And The Muslim World: A British View-Point.” Islamic Studies. Vol. V, No. 3 (September 1966): 283-304.

[20] Lee, Dwight E. “The Origins of Pan-Islamism.” The American Historical Review. Vol. XLVII, No. 2 (January 1942): 278- 287.

[21] [Beverley, H. Report of the Census of Bengal, 1872. Reports. Census Reports-1871. Bengal Secretariat Press. Kolkata, West Bengal, India. (1872): 86-87.]

[22] The Nawab writes: “[The Palace, Murshidabad, June 3, 1882.] Dear Sir, I have received your letter of [May 26,] informing me that a Branch Theosophical Society has been established at Berhampore, and a Library in connection therewith. I fully sympathize with the objects of the Society, and feel it a pleasure to contribute, in furtherance thereof, the sum of Rs. 400. It is highly desirable that every effort should be made for the regeneration of India, and the revival of its ancient glory; and I wish you every success in your noble undertaking. Yours truly, Hussan Ali Mirza.] “A Nawab’s Gift.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. III. No. 34. (July 1882): 4.

[23] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts and Consciousness of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June 1995): 16- 37.

[24] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts And Consciousness Of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June, 1995): 16- 37.

[25] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts and Consciousness of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June 1995): 16- 37.

[26] “A Spirit of Toleration.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) July 28, 1891.

[27] Holt, P.M. The Mahdist State in the Sudan 1881–1898: A Study of Its Origin, Development, and Overthrow. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1958): 32-44.

[28] Searcy, Kim. The Formation of The Sudanese Mahdist State. Brill. Boston, Massachusetts. (2011): 53.

[29] Mandel, Neville J. “Ottoman Policy and Restrictions on Jewish Settlement in Palestine: 1881-1908: Part I.” Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. X, No. 3 (October 1974): 312-332.

[30] Mandel, Neville J. “Ottoman Policy and Restrictions on Jewish Settlement in Palestine: 1881-1908: Part I.” Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. X, No. 3 (October 1974): 312-332.

[31] Keddie, Nikki R. “The Pan-Islamic Appeal: Afghani and Abdülhamid II.” Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. III, No. 1 (October 1966): 46-67.

[32] Lee, Dwight E. “The Origins of Pan-Islamism.” The American Historical Review. Vol. XLVII, No. 2 (January 1942): 278- 287.

[33] Holt, P.M. The Mahdist State in the Sudan 1881–1898: A Study of Its Origin, Development, and Overthrow. Oxford University Press. Oxford, England. (1958): 56.

[34] Searcy, Kim. The Formation of The Sudanese Mahdist State. Brill. Boston, Massachusetts. (2011): 53.

[35] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts and Consciousness of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June 1995): 16- 37.

[36] “A Master in Islam on the Present Crisis.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) April 11, 1885.

[37] Tal, Alon. “Enduring Technological Optimism: Zionism’s Environmental Ethic and Its Influence on Israel’s Environmental History.” Environmental History. Vol. XIII, No. 2 (April 2008): 275-305.

[38] “Solomon’s Temple.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) December 12, 1881; “Weekly Review.” The Preston Herald. (Lancashire, England) January 14, 1882.

[39] Johnston, Jas. Bainbridge. “A Pilgrimage To Jerusalem.” The Star. (Guernsey, Guernsey) July 6, 1882.

[40] Lee, Dwight E. “The Origins of Pan-Islamism.” The American Historical Review. Vol. XLVII, No. 2 (January 1942): 278- 287.

[41] Mandel, Neville J. “Ottoman Policy and Restrictions on Jewish Settlement in Palestine: 1881-1908: Part I.” Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. X, No. 3 (October 1974): 312-332; Stewart, Desmond. “Herzl’s Journeys in Palestine and Egypt.” Journal of Palestine Studies. Vol. III, No. 3 (Spring 1974): 18-38.

[42] Regarding the prophecy, it was said: “The tradition of the flight of Jeremiah from Jerusalem after the sacking of city the Romans, and of his voyage to Sicily with the Ark his possession, with his shipwreck on the coast of Ireland (still maintaining his hold of the Ark,) is once more recounted with unction. ‘The hollow cave on Mount Horeb,’ is said to be the description, veiled of course, of the real place of concealment, which is in reality none other than the cavern beneath the sacred hill of Tara. The tradition goes state that when Jeremiah had buried the Ark his followers sought to find the place where it was concealed, the prophet raised his hand to heaven and pronounced the words quoted in the second book of Maccabees, ‘The place shall be unknown until the time God shall gather his people again together and receive them unto mercy. Then shall the Lord show them these things and the glory of the Lord shall appear.’ The end of the two thousand years of expiation by the Jews is drawing nigh, and the two thousand years of their abiding by the law will ensue—when Messiah will appear the wicked kingdom have been destroyed.” [“The State of Egypt.” The Lincolnshire Chronicle. (Lincolnshire, England) July 28, 1882.]

[43] The Nawab writes: “[The Palace, Murshidabad, June 3, 1882.] Dear Sir, I have received your letter of [May 26,] informing me that a Branch Theosophical Society has been established at Berhampore, and a Library in connection therewith. I fully sympathize with the objects of the Society, and feel it a pleasure to contribute, in furtherance thereof, the sum of Rs. 400. It is highly desirable that every effort should be made for the regeneration of India, and the revival of its ancient glory; and I wish you every success in your noble undertaking. Yours truly, Hussan Ali Mirza.] “A Nawab’s Gift.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. III. No. 34. (July 1882): 4.

[44] “A Nawab’s Gift.” Supplement to The Theosophist. Vol. III. No. 34. (July 1882): 4.

[45] Searcy, Kim. The Formation of The Sudanese Mahdist State. Brill. Boston, Massachusetts. (2011): 53.

[46] Johnston: “The ‘Aryans’ enjoyed an unrivaled popularity, in every work on philology, or philosophy, or anthropology which had any pretensions at all to reflect the latest wisdom of the times. We were met on every page by eulogies on the superiority of the ‘Aryans,’ their high culture, unrivaled civilization, and inherent rights to dominate all “non-Aryan” peoples. We were even told, in all seriousness, that the ‘Aryan’ brain was not only of greater specific capacity than the cephalic content of the “non-Aryan,” but that it further possessed the wonderful capacity of continuing to expand at an age when the ‘non-Aryan’ brain had ceased to grow for several years.” [Johnston, Charles. “The Aryans.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (Madras, India) March 21, 1895.] From an excerpt from one of Atkinson’s 1882 lectures, we can see a glimpse of what Johnston means: “When, however, they compared the extremes of the present inheritors of the Aryan linguistic patrimony—the Hindoo and the Icelander—it seemed hard to conceive what basis there could be for the assumption of a common race. If this theory were maintained, some attempt should be made to remove the difficulties it involved. Of course in matters so remote history failed altogether as to the physical type of this Aryan race, so that they entered into the region of speculation through the portals of anthropology. They there learned that tracts occupied by this Indo-Germanic family constituted the chief seats of a peculiar race, and whose characteristics might be briefly stated as white, red, and blue in skin, hair, and eyes respectively, and as long-headed and large-bodied. The Indo-Romanic people, he believed, to have been this blonde race thus characterized.” [“The Origin Of The Kelts.” The Dublin Daily Express. (Dublin, Ireland) May 22, 1882.]

[47] From an excerpt from one of Atkinson’s 1882 lectures, we can see a glimpse of what Johnston means: “When, however, they compared the extremes of the present inheritors of the Aryan linguistic patrimony—the Hindoo and the Icelander—it seemed hard to conceive what basis there could be for the assumption of a common race. If this theory were maintained, some attempt should be made to remove the difficulties it involved. Of course in matters so remote history failed altogether as to the physical type of this Aryan race, so that they entered into the region of speculation through the portals of anthropology. They there learned that tracts occupied by this Indo-Germanic family constituted the chief seats of a peculiar race, and whose characteristics might be briefly stated as white, red, and blue in skin, hair, and eyes respectively, and as long-headed and large-bodied. The Indo-Romanic people, he believed, to have been this blonde race thus characterized.” [“The Origin Of The Kelts.” The Dublin Daily Express. (Dublin, Ireland) May 22, 1882.]

[48] Renan writes: “Religions are mighty by reason of the people that adopt them. Islamism has been useful or deleterious according to the races that have accepted it. Among the debased nations of the East, Christianity is a religion of very moderate merit, inspiring very little virtue. It is among the people of the West, the Celtic, Germanic, and Latin races, that Christianity has been truly fecund…In the beginning a wholly Jewish product, Christianity has come in this way, in the process of time, to shed almost every trace of its ethnic origin, so that the contention of those who proclaim it the Aryan religion par excellence is, from many points of view, well-founded. For centuries we have been infusing into it our Aryan ways of feeling, all our aspirations, all our good qualities, and all our faults […] Each race, in adopting the moral training of the past, gives them a new mold, makes them its own. The Bible has in this way borne fruits not its own; Judaism was only the wild slip on which the Aryan race has grafted its flower.” [M.W.H. “Renan’s View of Christianity.” The Sun. (New York, New York) November 25, 1883.]

[49] Masuzawa, Tomoko. The Invention of World Religions. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois. (2005): 169-171.

[50] De, Amalendu. “The Social Thoughts and Consciousness of The Bengali Muslims In The Colonial Period.” Social Scientist. Vol. XXIII, No. 4/6 (April-June 1995): 16- 37.

[51] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume III 1883-1887. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1904): 438.

[52] Olcott, Henry Steel. Old Diary Leaves: Volume III 1883-1887. Theosophical Publishing Society. London, England. (1904): 438; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 4026 (website file: 1B/30) Fuzli Rubeee Nawab Dewan; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 2615. (website file: 1A: 1875-1885) Janaki Nath Panni.

[53] Mukerji, K.P. “Religious Arbitration.” The Theosophist. Vol. IX, No. 102 (March 1888): 378.

[54] Johnston, Charles. “A Perspective On India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXXXVIII, No. 6. (December 1926): 848-856.

[55] “Unfounded Charges Against Orangemen.” Belfast Weekly News. (Belfast, Ireland) April 20, 1889.

[56] In West Bengal Doljatra, or the “Swinging Festival” was something of a spiritual-creole of the festival of Holi that was celebrated in the Upper Provinces. It was a celebration when offerings were made to the gods on the thirtieth solar Phálguna, or first of Chaitra; the fifteenth day, light-half, or full moon of Phálguna. When India was governed by native princes, and Hindu institutions were in full strength, a series of connected festivities spanned a period of several weeks called the Vasantotsava, or the feast of Vasanta (Spring) and Love. In those times, the Vasanta Panchami (the fifth of the light-half of Mágha) was regarded as the beginning of Spring and was observed by “lustral and purificatory rites.” Over time the festival of Holi supplanted the initiatory Vasanta Panchamí, and though traces of the original purpose of the festival, “Love and Spring,” were still observable, they were largely deposed from the rites over which they once presided. Newer “mythological creations” were “invented” to account for the origin of the celebration. In other Provinces, an effigy of Holika, an asuri (demoness) and “devourer of little children,” was committed to the flames of a bonfire. In Bengal, the focus of veneration was the young Krishna. Before sunrise on the morning of Doljatra, an image of Krishna was consecrated and sprinkled with a red powder known as phalgo made from the dried root of Amba Haldi (Curcuma Zerumbet.) Krishna was then carried to a swing which had previously been set up and placed in the seat. As soon as the sun rose, it was set gently in motion for a few turns. This act was repeated at noon, and again at sunset. During the day, the members of the family and their visitors amused themselves by scattering handfuls of Phalgo over one another, or by sprinkling each other with rose-water. A celebration of “licentious mirth,” analogous to April Fool’s Day, followed for several days. People ventured into the streets, “singing and dancing, annoying people with pranks, shouting coarse witticism and vulgar abuse, and scattering phalgo over one another.” [Wilson, H.H. “The Religious Festivals of The Hindus. Pt. I.” The Journal of The Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. IX. (1848): 60-110; Howitt, Mary Botham. Pictorial Calendar of The Seasons. Henry G. Bohn. London, England. (1854):175; Dutt, Shoshee Chunder. Historical Studies and Recreations. Vol. II. Trübner & Co. London, England. (1879): 99-102; Bose, Shib Chunder. The Hindoos as They Are. Thacker, Spink and Co. London, England. (1883): 156-161.]

[57] Johnston, Charles. “How The Army Was Kidnapped.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXIV, No. 4. (October 1914): 469-477.

LANMAN BIOGRAPHY

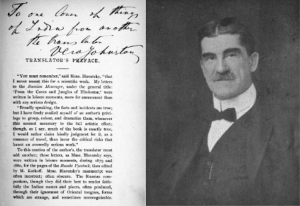

The Johnston’s possibly met the American Sanskritist, Charles Rockwell Lanman (1850-1941,) at this time, one of the two “friends and fellow workers,” whom Johnston dedicated his 1908 translation of the Bhagavad Gita and dedicated singularly his 1912 work The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.[1] It is evident that they knew Lanman on some personal level, as Lanman’s copy of From The Caves And Jungles Of Hindostan (1892,) contains a personal note from Vera Johnston: “To one lover of things of India from another—the translator, Vera Johnston.”[2] (Other Theosophical works in Lanman’s library included the 1897 edition of Claude Falls Wright’s An Outline Of The Principles Of Modern Theosophy.)

Charles Rockwell Lanman.[3]

A native of Norwich, Connecticut, Lanman received his education from Yale University, taking up Sanskrit under William Dwight Whitney. When Johns Hopkins University opened in Baltimore in 1876, Lanman accepted the position of Assistant Professor of Sanskrit. In 1880 Lanman joined the faculty of Harvard University, becoming the first to preside over the department of Indo-Iranian Languages.[4] 1884 saw the publication of the celebrated A Sanskrit Reader: With Vocabulary and Notes.[5] Together with Maurice Bloomfield (a fellow protégé of Sanskrit scholar, William Dwight Whitney,) Lanman would train nearly every Sanskrit professor teaching in American universities in the early twentieth-century.[6]

Like Johnston, Lanman was a newlywed, having married his wife, Mary Billings Hinckley, in July 1888.[7] After sending a revised edition of A Sanskrit Reader to the printers in December 1888, Lanman and Mary set off for India.[8] On January 16, 1889, just around the time that the Johnstons were settling in at Murshidabad, Lanman was the “first representative of the flourishing school of American Orientalists” to visit the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.[9] During his time in India, Lanman would secure nearly 500 Sanskrit and Prakrit manuscripts for Harvard; texts which would form the nucleus of the college’s Sanskrit Library, and Harvard Oriental Series.[10]

Irving Street, Cambridge Massachusetts c. 1888-1889.[11]

Upon returning to America, Lanman would build a house in the Shady Hill neighborhood of Cambridge, adjacent to the homes of his friends, William James, and Josiah Royce (who, too, were building their homes on Irving Street.) Both Lanman and James belonged to the Harvard History of Religions Club and were known to hold discussions on Indian philosophy.[12] Though Lanman does not appear to have joined the Theosophical Society like William James, it would seem that he was sympathetic to its aims.[13] During his tenure at Harvard Lanman would deliver lectures with titles like, “Theosophy, Transmigration, Karma, and Caste,” and give examination papers on the Upanishads, which he called “The Theosophy of India.”[14]

Mt. Vernon Street & Joy Street.[15]

Lanman likely met W.Q. Judge in February 1894, when the latter was in Boston in connection with the “housewarming” of the New England Theosophical Corporation (24 Mt. Vernon Street.) On February 16, 1894, under the auspices of the Harvard Religious Union, Judge delivered a lecture, “The Underlying Basis of All Religions,” in Harvard’s Holden Chapel.[16] The President of the Harvard Religious Union was William Healy, who would become a “devoted member” of the Theosophical Society. Healy formally joined the Society just two weeks prior to Judge’s arrival. A future pioneer in psychoanalysis, and criminology, who would one day establish the first child guidance clinic in America, Healy, at the time, was just a twenty-four-year-old student. He enrolled in Harvard University a year earlier, in 1893, as a “special student,” and taking several courses with William James, Healy came to know his mentor quite personally.[17] On February 18, Judge delivered a lecture titled “The Masters of Wisdom,” for the Cambridge T.S. on the first floor in Alden and Harlow’s new Brattle Hall (which they began leasing in 1894.)[18] “About three hundred persons,” were in attendance, with “many being Cambridge professors,” one of whom being William James.[19] Marguerite Loring Guild, the Cambridge T.S. President, then entertained a number of visitors at her home at 16 Ash Street (the future home of Lanman’s pupil, T.S. Eliot.)[20] If Judge did not meet Lanman at this time, he was most certainly aware of him by the autumn of 1894. When embarking on the creation of The American Asiatic and Sanskrit Revival Society, Judge states: “For years America has had to depend upon European societies in the matter of Oriental research. The first break was made by Harvard College, where a private collection was started consisting of 1,000 manuscripts, 500 of which were contributed by Prof. Lanman.”[21]

In the ensuing years, Lanman would develop connections with others in the Theosophical orbit, including Anagarika Dharmapala and George de Roerich (whom he taught Sanskrit and Pali.)[22]

LANMAN SOURCES:

[1] Johnston, Charles. Bhagavad Gita: The Song of the Master. The Quarterly Book Department. New York, New York. (1908): Dedication; Johnston, Charles. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Charles Johnston. New York, New York. (1912): Dedication.

[2] Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna; Johnston, Vera (tr.) From The Caves And Jungles Of Hindostan. Theosophical Publishing society. London England (1892): iii.

[3] Belvalkar, S. K. “In Memoriam C. R. Lanman.” Annals Of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Vol. XXII, No. 3/4 (July-October 1941): 300-04.

[4] “Sanskrit For Harvard.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 2, 1880.

[5] Lanman, Charles Rockwell. A Sanskrit Reader: With Vocabulary and Notes. Ginn, Heath, & Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1884):.

[6] Tull, Herman. “Whence Sanskrit? (Kutaḥ Saṃskṛtamiti): A Brief History of Sanskrit Pedagogy in the West.” The International Journal of Hindu Studies. Vol. XIX, No. 1/2 (April-August 2015): 213–256.

[7] “Table Gossip.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts.) July 29, 1888; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1840–1911. New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts. Massachusetts Vital Records, 1911–1915. New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

[8] Lanman, Charles Rockwell. A Sanskrit Reader: With Vocabulary and Notes. Ginn, Heath, & Company. Boston, Massachusetts. (1888): iii-x.

[9] “Professor Lanman On Oriental Studies In America.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts.) May 3, 1889.

[10] Belvalkar, S. K. “In Memoriam C. R. Lanman.” Annals Of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Vol. XXII, No. 3/4 (July-October 1941): 300-04.

[11] Cogswell, Charles N. Cogswell Photograph Collection. Cambridge Historical Commission. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Collection ID: P014. (1883-1921)

[12] Cushman, Esther Lanman. “Where the Old Professors Lived.” The Proceedings Of The Cambridge Historical Society. Vol XLII. (1970-1972): 13-30; Taylor, Eugene. William James On Consciousness Beyond The Margin. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey (2011): 62; Croce, Paul J. Young William James Thinking. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland (2018): 177.

[13] William James joined the Theosophical Society in 1891. [Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 7197. (website file: 1C: 1890-1894) Prof. William James (Joined 06/25/91.)]

[14] “To Talk On Brahminism.” The Harvard Crimson. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 27, 1925; J. “Emerson And Asia.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXVIII, No. 2 (October 1930): 202-204.

[15] “View Of Mount Vernon Street, Looking Toward State House, Boston, Mass., 1902-1905.” Historic New England. DigitalID 001513. AccessID 2343. Other identifier HNEDID-001513. General photographic collection. PC001.02.01.USMA.0340.5770.002.

[16] “University Organizations: Harvard Religious Union.” The Harvard Crimson. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 16, 1894; “Lecture By W.R. Judge.” The Harvard Crimson. (Cambridge), February 17, 1894.

[17] Bennett, James. Oral History and Delinquency: The Rhetoric of Criminology. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, Il. (1988): 114; Snodgrass, Jon. “William Healy (1869-1963): Pioneer Child Psychiatrist And Criminologist.” The Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences. Vol. XX. (October 1984): 332-339.

[18] “Theosophical Hall.” The Cambridge Tribune (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 9, 1895.

[19] “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Tribune. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 17, 1894; “Old Cambridge.” The Cambridge Chronicle. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) February 17, 1894; “Mirror of the Movement.” The Path. Vol. VIII, No. 12. (March 1894): 439-442.

[20] Jones, Edward A. Blue Book Of Cambridge. Advertiser Publishing Company. Boston, Massachusetts (1895): 241; Crawford, Robert. Young Eliot: From St. Louis to The Waste Land. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. New York, New York. (2015): 173; Miller Jr., James E. T. S. Eliot: The Making of an American Poet, 1888–1922. Penn State Press. University Park, Pennsylvania. (2005): 172; Spurr, Barry. Anglo-Catholic In Religion: T.S. Eliot And Christianity. The Lutterworth Press. Cambridge, England. (2010): 5.

[21] “To Seek Hindoo Manuscripts.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (St. Louis, Missouri) December 17, 1894.

[22] “School And College.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) November 24, 1903; “The Anagarika Dharmapala’s Lecture.” The Harvard Crimson. (Cambridge, Massachusetts) November 24, 1903; de Jong, J. W. “George N. de Roerich 1902–1960.” Indo-Iranian Journal. Vol. V, No. 2 (1961): 146-152