THE PHANTOM PALKI.

Charles Johnston.

Late November 1889.

I remember a certain camping ground in the cool heart of a mango grove. The lucid air was full of the cooing of turtle doves; golden orioles flashed through the dense green of the branches; gray squirrels chattered like Bengali schoolboys. Our tents, white pyramids mottled with deep shadows, had come to that remote outland in order that I might hold elections for the District Board.

After a ride in the cool of dewy morn, a soul-refreshing shower bath, and tea and toast served by my scarlet-turbaned butler, I drove along a road already blistered by the sunshine to the neighboring thana—that is, a rural police headquarters—where the elections were to be held. A crowd was already there, squatted in Oriental fashion in the blots of shadow beneath the trees of the thana garden; dark brown cultivators, almost black—for there is a great deal of Dravidian blood in East Bengal—girt about the loins with a strip of cotton, smoking their clay hookahs in supreme content. Seated on the veranda of the thana was a little group of Bhadra Lok, Bengali gentlemen, as they love to call themselves, who rose and greeted me with some ceremony:

“Your Honor’s body how is?” That is the correct thing in high Bengali; my Honor’s soul being presumed to be in a state of grace. The cultivators, who had promptly risen to their feet, in their greeting, with profuse bows, applied to me such flattering terms as “Umbrella of the Poor! Incarnation of Virtue!”

Standing on the well shaded veranda, with the Bengali gentlemen at my right and the Police Sub-Inspector at my left, I made the assembled voters a little speech in my best Bengali, beginning with the equivalent for “Gentlemen!” at which the cultivators nudged each other in some perturbation; I doubt whether the Bhadra Lok were altogether pleased.

I told them that the Government—which they still call “The Company,” though the East India Company has been dead these sixty years—solicitous for their welfare, and eager to bestow upon them a larger measure of self-government, had decreed the organization of an elected Board for every District—that is, for some million or so of dusky souls—and that they had been summoned, on that November morning, to select, of their own free choice, some one of themselves, in whom they had confidence, to represent their group of villages upon that Board. Other groups of villages would do the like; then the elected personages, meeting together at the Sadr Station—the District metropolis at Berhampore—would assume control of certain things throughout the District: such as roads and bridges, hospitals and schools, levying, for that purpose, light tax, according to their discretion, to pay the bills.

There was much concerned whispering among the assembled rice-growers. Finally a spokesman came forward with a profound obeisance, which signified that his neck was beneath my instep. We deprecate that sort of thing, but it is bred in the Oriental bone; you might as well try to stop the Ganges.[1]

“Whom does your Honor wish us to elect?” The spokesman came to the point at once, while the Bhadra Lok cast their eyes down in conscious merit.

I explained, in such Bengali as was available for so un-Oriental an expression, that that was up to them. The Government, in its benign wisdom, wished them to choose according to their liking. It was to be a genuine election, wholly uncontrolled. Then I sat down and left them to think it over.[2]

The Bhadra Lok also sat down, after a courteous interval, and Bhangshi Babu, on my immediate right, opened a flowery conversation about the weather, the prospects of the rice crop, the flood that had recently swamped the District. Bhangshi Babu was a Brahman with fine Roman features, ana owner of a large patchwork estate dappled over a score of villages—the outcome of their inheritance laws. There was a thread of self-consciousness running through his talk, the meaning of which was presently revealed. For, after much whispered consultation among dusky groups, where sluggish mental action was stimulated by much hookah smoking, till the air was full of acrid fumes, the spokesman came forward again with another salaam:

“May we elect Bhangshi Babu, Protector of the Poor?” And that Bengali gentleman looked down, but there was the wraith of a smile in his fine Brahminic eyes.

I was not there to electioneer for him or anyone, even though of quintessential Brahman blood, so I explained that they could choose whom they pleased, whether Bhangshi Babu or another. I do not think the Bengali gentleman was quite pleased. But he said:

“I can understand! Such a sentiment is acceptable? between friends!”

After a few more words of consultation, interrupted by “Ha!” the Bengali equivalent of “Yes!” the spokesman returned:

“We think we had better choose Bhangshi Babu, Protector of the Poor!”

So I shook hands with the successful candidate, and the thing was done.

The free and independent voters had evidently got their instructions from their landlord, and voted for him with meek unanimity.

There is the rub when it comes to self-government for India. The danger, and every Anglo-Indian recognizes it, is, that we may put back into power the Brahmanical hierarchy which, by all the wiles of priestcraft, by organizing aboriginal idol-worship and blood-sacrifices, by astrology and “miracles,” has held the lowlier races of India en slaved, body and soul, these three thousand years. Even the English-speaking Masters of Art of Calcutta University, after their graduation, go back to temples reeking with the blood of bulls and goats, and chant Vedic mantras before hideous idols. Exactly so far does their study of Mill and Huxley emancipate them. And this, in flat defiance of the fact that all the best of their sacred books sternly condemn this evil ambition and its instruments, black superstition and idolatry, the things against which the Buddha made his heroic protest.[3] But long centuries ago, the dark Brahmanical reaction drove the Buddha’s followers out of India.[4]

~

It was a dappled afternoon in late November. We had turned our eyes toward the town of Kandi. From the deep green shadow of the mango tope, one could see its nearest buildings, gleaming white in the outer sunlight, beyond a shimmering carpet of rice-stubble. One glanced for a moment at the sun-steeped houses, and then drew back with a sigh of deep content into the umbrageous quiet of the grove. Ritchie addressed me, pointing toward the buildings out in the heat—

“I expect to put you in charge over there, in January; the Deputy, Soshi Sikar Dutt, has two months’ chuti; going to make a tour of his fathers-in-law!”[5]

I heard, in pleasurable anticipation, and looked forth with new interest toward Kandi, glistening there in the sunshine.

In Camp (Source: Old Indian Photos.)

Evening had come. Our camp broke up and faded creakingly through the twilight in a long train of native ox-carts down the twenty miles of dust-bedded road to the Bhagirathi River and Berhampore.[6]

I had made arrangements to return to Berhampore by palki, to arrive the next forenoon. Punaswami of the red turban had fed me on wooden-flavored moorghee and tiny potatoes, with really good coffee and a cigarette, and I was ready to go.

The palki-bearers were standing about, whispering, and laughing; big, stalwart chaps, grayish-yellow in color, with large cheek-bones and huge hands and feet.[7] There was evidently a lot of Santal blood in that part of the subdivision.[8]

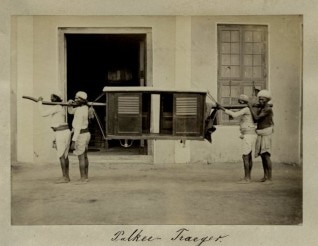

An awkward thing to get into a palki. You have to sit down on the and crawl in, and when in, you must lie down; there isn’t room to just sit up without bumping your head. Just a long box with a sliding side-door, and swung on two long bamboos; comfortable enough, though, to sleep in.

So, feeling decidedly self-conscious, I sat me on mother earth, and sideways into my box.

“All ready! To Berhampore!”

It was one of those lovely that the beginning of the cold season brings, not too warm, and scented like a garden. My bearers swung the palki up on their shoulders and pattered barefoot in the dust, chanting a jig-jog song that Kipling renders, “Let us take and heave him over! Let us take and heave him over.”[9]

Palki & Palkiwallahs (Source: India.Com)

We took a short cut across the rice-fields and by the edge of a bit forest. There were huge trees, their boughs twisted together, and hung with masses of a kind of wild cucumber whose tendrils were like enormous skeins of yellow floss silk, with here and there a scarlet fruit hanging down, like a huge Easter-egg, A fine wildness about it all.

“Let us take and heave him over! Let us take and heave him over!”

They could, too, with the greatest ease. Here am I, twenty or thirty miles from the nearest man of white race, absolutely defenseless, unarmed, amid three hundred thousand natives according to the last census, who might easily enough have a grudge to wreak; but I am trusting myself to their tender mercies in complete confidence. I suppose a Deputy Magistrate could not disappear without some stir! The paternal government would look him up…Might not do him much good, though…However…

At this point I went to sleep…Something very soothing about the jog-jog of a palki and that “heave- him-over” song and the patter of feet on the earth…

Once, during the night, I was wakened by the wild, diabolic yelling of jackals, an inferno broken loose in midnight jungle. Something startling and hair-raising about jackals; they begin so unexpectedly…But I rolled over and went to sleep again, with patter-patter in my ears.

Then we came to a stop, and was some kind of a row among the palki-bearers. That wakened me again. I pulled open the sliding-door, and, in curt phrase of Anglo-India, said—

“Shut up, dogs, and let me sleep!”

They did, and I slept—till morning this time, waking when it was full sunlight, with the expectation of recognizing the Berhampore landmarks the roadside.

One thing intrigued me: we seemed to be jolting uphill. But there isn’t a hill within thirty miles of Berhampore, or anywhere in the delta; not even a mound as big as an ant-hill. So I slid the door open to see.

“Where the mischief—?”

We were in thick jungle, a hillside apparently, with a kind of cattle-track running up it, under huge, matted trees laced together with creepers like tangled skeins of yarn thrown over the branches. A kind of green gloom, and a fresh coolness in the air.

I shouted to the bearers to stop. They stopped, and I crawled out, in the wormlike, undignified fashion inseparable from palkis, and repeated my question—

“Where the mischief are we?”

I repeated my question in English, chiefly for my own benefit, in Bengali, in Hindi. The bearers only grinned sheepishly and shook their heads.

I was very angry and made vigorous use of the vocative case and the imperative mood. I might as well have spoken in pluperfect subjunctives, for they evidently did not understand a word.

Like the harmattan wind, I raged myself out, and saw that it was perfectly useless to talk to these gray-yellow dunderheads, who grinned foolishly at my best objurgations.

I began to realize that I was getting hungry. Also I wanted a smoke.

Fortunately this last want was easily supplied. I had the makings and matches. So I sat down on a rock—there isn’t a rock in Berhampore, or in all the delta, for that matter—and rolled and lit a cigarette. That appealed to those yellow-gray kidnappers. They produced tobacco leaf from their dingy shoulder-cloths, a knot in the corner of which forms a Bengali pocket, and began to roll al fresco cigars. They even had the cheek to borrow my matches—with such child-like innocence in their eyes that I gave them. So we all smoked, out there in the jungle. They were very respectful, nay, deferential, for all their kidnapping, and if I had had some breakfast, say some good coffee and rolls, it would not have been half bad. But I was beastly hungry and getting hungrier. What had become of Punaswami of the scarlet turban, I could not even speculate on.

Finally I appealed to an old chap among the bearers—there were eight of them, two relays—who had crisp white hair on his head and jowl, and a mat of white hair on his chest. I said to him in English—

“Old gentleman, please get me some breakfast!”

He shook his head and replied, at great length, in a tongue of which I did not know a word, but which I guessed to be the Santali of the hills.[10] We can see them, pale blue on the horizon, from the western edge of the subdivision. As we were palpably among hills—or at least upon one hill, you couldn’t see much of anything, because of the dense jungle—and as there weren’t any other hills, I supposed must be the ones. So the old gentleman talked, very eloquently, and with gestures; but from all his eloquence no breakfast supervened. I wasn’t even certain that he was talking breakfast but I was quite certain I wanted mine.

So I fell back on a language practical than Esperanto or Volapük—I opened my mouth and pointed down my throat. That evidently home. The old gentleman’s face lighted up, he smiled luminously and pointed up the trail through the forest. Then he pointed to the sliding door of the palki. That was good sense. If breakfast would not come to me, I must go to breakfast, and the palki was the only way. I did not even consider walking back along the track we had come, because I knew that, in that direction, breakfast was at least forty miles off, and the jungle fairly well stocked with big game—leopards, tigers, to say nothing of snakes—and my weapons were a box of matches and pencil.

So I sat down on the ground, and slid back into the palki, to the evident relief of my bearers, who me and went forward, seemingly rejoiced in their minds.

About noon—I had beguiled the hours, and tried to beguile my appetite with cigarettes—we came to a clearing, and they set the palki down.

A horribly undignified way to one’s entrance, crawling out of a beastly box, but it had to be done. A crowd was there to receive us, the same gray-yellow folk with big cheek-bones, chiefly adorned with peacock feathers stuck jauntily in their hair; and, among the leaf-mat huts, a mob of women and children.

I got on my feet and looked about. The crowd gathered about deferentially, saluting by bringing their fingertips up to their foreheads and then stretching out their arms, as if they were going to dive; apparently Santali for “Good morning!”

The old gentleman from among my bearers then saluted a revered old person in the crowd and made a little speech. The old person seemed pleased. He said something monosyllabic and unintelligible to my bearer and then stepped forward, and said to me, in fairly good Bengali—

“Incarnation of Virtue! We offer you respectful salutations!”

I replied that I was glad of it, and asked—

“Where are we? Who are you? And why, in the name of Mahadev, have you brought me here?”

Here is his astounding reply, just as he made it—

“Umbrella of the Poor! This is a village of Men, whom the Bengalis call Santals. We have a Babu. We are going to kill him, and we wished your Honor to be present, to see!”

“‘We have a Babu, and we are going to kill him—’ just that. It took my breath away.

Astonishment, the desire to gain time, and primitive instinct, worked together in my reply—

“That is all very well. But you must not kill him until I have had some breakfast.”

So they fed me, under the village fig tree: India-rubber like moorghee, with curried vegetables, and the finest rice I ever tasted. But no coffee, and I particularly wanted coffee.

As I ate, the dignified elderly person sat beside me, very affable and friendly. I approached the question obliquely—

“How does it come that you speak such good Bengali?”

My speech was really more polite than that. These Oriental tongues have shades.

“I spent ten years in Berhampore,” he replied very courteously, “in Sadr jail. I was on road gang at Kandi, and the foreman—a Bengali pig—hit me, so I killed him. The judge asked who did it, and I of course told him, so I was sent to jail. I learned Bengali, and, because of my knowledge of English law, my people have elected me Headman.”[11] And he smiled, very much pleased with himself.

Yes; English law; but how about killing babus? I put it a little less directly, but it amounted to that. He said that, of course, this was different. He would make it all plain after breakfast, and then they would kill the Babu. Everything should be done in an orderly way.

All the men had spears, as well as their jaunty peacock-feathers. I, as I have said, was armed with a lead pencil; not even a fountain-pen. If it came to physical force, it was a blue look-out for the Babu. Fine, vigorous men, too, manly, open faces. One could not browbeat them, as if they were Bengalis. I began to be anxious about that Babu.

After breakfast, a cigarette. I drew it out as long as possible and considered. Oh, Indranath Babu, why are you not here, to warn me off shoals by your clucking? I wish you were, but, since you are not, I must go it alone.

So, my cigarette ended—and I felt rather like a condemned man with his last cigar, at the end of which the proceedings are to culminate, we all went to the village grove, where the prisoner was brought, tightly bound, haggard, disheveled, wild-eyed. A Bengali, undoubtedly, but a very ill-used Bengali, physically speaking.

Suddenly I caught his eye. He was making signs. I went over to him, in the midst of his guard of sturdy spear men.

He half-whispered, in English—

“Sir! Do you not know me?”[12]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] Johnston writes: “In all cases, every effort is made by the English officials to get the natives used to the idea of voting, of elections and the rest of the machinery of democracy. It has been my lot to go out camping through the District, to hold the Local Board elections, and I can testify to the sincerity and thoroughness with which these efforts are made. I can also testify to the wonder, not unmixed with suspicion, with which the Bengali villager regards the whole proceeding.” [Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India.” Proceedings of the American Political Science Association, 1906, Vol. III., Third Annual Meeting. (1906): 169-179.]

[2] This experiment in limited self-government was implemented by Steuart Bayley in 1887, whereby local politics were redirected to District and Local Boards. [“Self-Government In Bengal.” The Madras Weekly Mail. (London, England) December 11, 1889.]

[3] Johnston writes: “We have dominant on the one side,-whether through poli tical or religious influence—races like the Rajput and the Brahman, and the castes of mixed blood that cluster round them. Of these, since our military supremacy, following on the Mughal and Mahratta arms, has dwarfed the power of the Rajputs, the most influential are certainly the Brahmanical group, the men who carry in their blood the theocratic traditions of Manu; in whose ideal the gods are a little lower than the Brahmans, under whose feet all other men have placed their necks. The traditional methods of this, the Brahmanical class, have always been to hold pre-eminence: first, by spiritual purity and moral force; then, when their earliest ideal has been deserted, they have secured their power by every artifice of priestcraft and tyranny of superstition: by the methods of the augur, the astrologer, and soothsayer. It is this class, with their skill in speech, their literary talent, and their diplomatic habit of shadowing the opinions of their political superiors, which our bureaucratic government in India has brought to the front. Our University education on English models has opened to them new vistas of power, as officials, lawyers, and, lastly, eloquent politicians, adapting to their own ends the ideals and methods of the doctrinary politics of Europe. These Asian Britons and effusively loyal subjects of Her Majesty, who have laid aside their old theocratic ideals to talk of the rights of democracy and the triumphs of the Great Charter, are, in traditions, instincts, and blood, the lineal descendants of the priestcraft of Manu, who ground the other India with tyrannous heel, enslaving souls for this world and the next.” .”[Johnston, Charles. “Home Rule And India.” The Calcutta Review. Vol. C., No. 200. (April 1895): 244-252.]

[4] Johnston, Charles. “Okhoy Babu’s Adventure.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXIV, No. 3. (September 1914): 309-316; Johnston, Charles. “Fuller Liberty For India.” The North American Review. Vol. CCIX., No. 763 (June 1919): 772-780.

[5] In Johnston’s original text, he writes: “I expect to put you in charge over there, in January; the Deputy, Govinda Babu, has two months’ chuti; going to make a tour of his fathers-in-law!” [Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India: Kandi Subdivision.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 2. (February 1912): 265-273.] Ritchie could be referring to Govinda Chunder Bose, the First Munsif of Kandi who was allowed three months’ leave at the end of January (1890.) [“Judicial Departments.” The Calcutta Gazette. (Calcutta, India) February 6, 1889.] The Englishman’s Overland Mail, however, states that Johnston was appointed to Kandi when Soshi Sikar Dutt went on leave. [“The Bengal Services.” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (Calcutta, India) February 25, 1890.]

[6] Johnston, Charles. “Helping To Govern India: Kandi Subdivision.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CIX, No. 2. (February 1912): 265-273.

[7] In “The Yellow Men Of India,” Johnston writes: “In a […] study of the races of North-Eastern India, based on close observation of the inhabitants of the old metropolitan district of Murshidabad, I found it necessary to group the Bengalis under three quite different race-types. The first of these, the fair-complexioned Aryan, formed a very small minority, and included the nucleus only of the Brahman caste. The representatives of the second Bengal race-type, the Indo-Chinese, with high cheek-bones, eyes aslant, and a dusky yellow skin, were much more numerous; and were, for the most part, industrious and skillful agriculturists.” [Johnston, Charles. “The Yellow Men Of India.” The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental And Colonial Record. Vol. V, No. 1 (January 1893): 102-118.]

[8] The Santal were a people whose mountain home was originally in the Himalayas. They now lived in the western frontier of Bengal, almost from the sea to the hills of Bhagulpore, on an extent of country about 400 miles long and 100 miles broad. [Wardle, Thomas. “History And Description Of The Growing Uses Of Tussur Silk.” Journal Of The Society Or Arts. Vol. XXXIX, No. 2,012. (June 12, 1893): 608-651.]

[9] From Kipling’s “My Own True Ghost Story,” from The Phantom Rickshaw (1888) in which he writes: “Just when the reasons were drowsy with blood-sucking I heard the regular—’Let-us-take-and-heave-him-over’ grunt of doolie-bearers in the compound. First one doolie came in, then a second, and then a third. I heard the doolies dumped on the ground, and the shutter in front of my door shook. ‘That’s someone trying to come in,’ I said. But no one spoke, and I persuaded myself that it was the gusty wind. The shutter of the room next to mine was attacked, flung back, and the inner door opened. ‘That’s some Sub-Deputy Assistant,’ I said, ‘and he has brought his friends with him. Now they’ll talk and spit and smoke for an hour.’” [Kipling, Rudyard. The Phantom Rickshaw. A.H. Wheeler & Co. Allahabad, India. (1888): 36.]

[10] In “The Yellow Men Of India,” Johnston writes: “The Santalis claim to be an ancient race, with traditions of a mighty past, when they had kings and cities of their own, before they were driven from their former home by invaders. They speak a highly elaborate and complicated language, which is entirely non-Aryan, both in vocabulary and grammar; and they still have a large body of traditional songs, which are handed down from generation to generation. They have a peculiar theogony, with legends of the destruction of the human race by fire and flood, and the birth of the seven original Santali tribes from the survivors. Later, they had twelve tribes, the added five being deemed inferior; and each tribe contained twelve families: only eleven tribes now exist.” [Johnston, Charles. “The Yellow Men Of India.” The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental And Colonial Record. Vol. V, No. 1 (January 1893): 102-118.]

[11] The Santal village government was purely patriarchal, and every hamlet had an original founder, or Manjhi Hanan, who was regarded as the father of the community. He received divine honors in the sacred grove, and transmitted his authority to his descendants. The Headman whom Johnston encountered, Sundra Manjhi, would have had the unchallenged sway which belonged to a hereditary governor; but he only interfered on great occasions, and usually left the details to his deputy, or Paramanik. The missionaries who lived for some years among the Santals told stories to outsiders that they had never seen an abuse of his power, and every chance traveler could not help but remark on the facility with which they could get food, guides, and transportation, in short, everything, just from a single word from their Headman. [Hunter, William Wilson. The Annals Of Rural Bengal. Smith, Elder And Company. London, England. (1897): 215-218.]

[12] Johnston, Charles. “Okhoy Babu’s Adventure.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXIV, No. 3. (September 1914): 309-316.