TUSSAR SILK.

Charles Johnston

January 1889.

We were driving along a country road with Eugène Gallois, a comfortable, gray little Frenchman, clean shaven, and an inveterate gossip. There was chivalry in his heart, and a dash of sadness where some old love story had left its incurable pain. The dust lay inches thick in the road, and rose in wreaths under the horses’ hoofs and after the wheels. The sky above was like brass. The kites soared and shrilled above us, and far away up in the blue faint specks showed where vultures circled.

Ragged palm trees lined the wayside, all crooked, no two bent alike. Their stems were rough and scarred, the dry leaves at the top scanty and scrubby. Stiff, lifeless cactuses, bristling with long white thorns beside the road, added to the dismal face of the wilderness. With a pensive twinkle, Eugène watched the palmyras drift past us, bare of grace or beauty; their stems were bent and crooked, their crest of ragged leaves unkempt. Eugène addressed Verochka.

“Do you know the proverb about the palm tree, madame?”

“Non, monsieur,” answered Verochka, who, being of the Russian persuasion, dearly loved to talk French.

“Two things you see once in a life time: a perfectly straight palm tree, and a lady who does not want the last word. I once saw a perfectly straight palm tree,” he added, in his brisk mischievous way. I intervened to prevent homicide.

To us, round a corner of the road, entered a group of brown Bengalis natives, cultivators of the soil, three women and two men, like draped bronze statues. They were withered brown, lean, and dejected, clad in faded cotton waist cloths with a twist of cloth on their heads, meant for turbans. Sad, discouraged faces, yellow eyes with red veins from too much rice wine. They take their liquor sadly. There was something arid and desolate in their whole bearing; the forlornness of a worn-out race whose lives are least blessed among the children of men. Each woman carried, poised on her head, and steadied by a statuesque right arm, a broad deep basket, heaped up, as it seemed, with golden almonds brilliantly yellow against the green jungle. From the size of the basket, it was evidently something very light, and I had never seen anything, whether in India or elsewhere, of that peculiarly vivid golden yellow. Verochka and I at first suggested some kind of fruit, perhaps dates, but even the yellow dates of Persia would be dim in comparison with that shining basket full of golden stuff.

Eugène smiled a superior smile at our perplexity.

“Something in my line,” he said.

“Comment, monsieur?” interrogated the lady,

“Silk, madame; cocoons going to the filature, to be wound.”

“Comme c’est joli!”

“Merci, madame,” said Eugène, raising his white helmet with a gallant little bow, as though the prettiness of the silk were something personal to himself.

That was the first time I had come across silk in its native land and its natural condition; but that beginning was followed by a swift development of circumstances so that during the next day or two I think I saw every stage of the process through which the silk goes from egg to the finished article as it appears in shops.

It may seem odd at first to speak of silk coming out of an egg; yet here in Bengal the egg state is one of the most important and has been the subject of volumes of memoirs, of endless experiments of an enormous outlay of time and money. And here, at Berhampore, is the very center of a series on investigations, in which the eggs of the silk work moth go through an investigation as searching as the trials of a battleship.

The silk worm is subject to almost as many ills as man; but the worst of them is parasitic which bears the name pibrine. This parasite sucks the life out of the silk-worm, and the unfortunate peasants and their families, after spending months tending their mulberry fields, and feeding their silk worms, had to watch the luckless worms dwindle and die, and see the whole fruit of their industry ruined. With people who are already on the verge of starvation, this was a sufficiently serious evil, but one which they were wholly unable to combat, and stark ruin stared them in the face.

The great silk factories, finding their supplies diminishing year after year, and hearing complaints from natives of this mysterious disease which came down upon like a scourge of demons in which they devoutly believed, were gradually forced to investigate the question, to see if anything could be done to abate the evil.[1] The Government set apart a small sum yearly for this purpose and appointed Nitya Gopal Mukerji, a native of Bengal who knew English well, and had passed brilliant examinations in natural science, to study the question thoroughly and suggest a remedy.

It was soon discovered that the disease which had for years been preying on the silkworms was due to a parasitic insect, which followed the silkworm from the cradle to the grave. No precautions at late stages of the silkworm’s life were of any avail; after all possible care had been taken it was found that the disease broke out as obstinately as ever. A drastic measure was adopted. It was decided that whatever means were to be taken must be adopted at the very threshold of the insect’s life, namely, while it was still in the egg, a minute black caterpillar, hardly thicker than a hair, curled up in a white transparent shell about as big as a grain of mustard seed.

Drying Cocoons In The Sun.[2]

So thousands of eggs were examined under a high power microscope, eggs brought from all parts of India, eggs brought from China, from Persia, from Turkestan; even from France and Italy, until a certain number of eggs were found, which even under the highest magnifying power, showed no signs of the pibrine parasite.

All eggs which showed the presence of the parasite, in quantities even the most minute, were destroyed, and then a further series of experiments was begun with the remainder. Nitya had a building assigned to him, and in it he proceeded to rear generation after generation of silkworms and their descendants in huge shallow trays, something like the head of a drum, and apparently made of skin stretched across a round hoop, and he had some dozens of these trays full of silkworms. I noticed a curious low, humming sound everywhere through the building, but for a long time I could not find the cause of it. At last I discovered that the noise came from hundreds of thousands of silkworms eating, and crawling about on the trays, whose drum-like floors took up the noise, and gathered it into a sufficient volume of sound to fill the whole building with a low, rasping rumble. The silkworms, in their big round trays, were not pretty to look at. They were simply big white caterpillars, with green legs and green markings, and if possible, even more fat, sluggish, and ungainly than the race of caterpillars in general. It is curious that they begin life black and later on turn white with green specks. When they first came out of the egg, they are thin little things about an eighth of an inch long. But they lose no time going to work on the mulberry leaves, not waiting to be spoon fed, or weaned, or delicately treated in any way, but simply getting right down to business on the day of their birth.

Placing Silkworms In The Spinning Trays And Removing The Cocoons.[3]

And they begin growing immediately, and they continue to eat and to grow, with a steady industry well befitting the role they are to play in decorating the world. And here we may say a word about their main and indeed sole article of diet, the mulberry leaf. I had imagined that the mulberry was a spreading tree, as big as a cherry tree, and that the natives went out to the forest to gather its leaves for the silkworms, but this was not the least like the reality. The fields of mulberry, for it is grown in fields, look more like potato fields than anything else I had ever seen. The plants were never more than a foot and a half or two feet high, they were planted in rows, and as carefully weeded and watered as if they had been some special kind of early potato.

The watering of these mulberry fields is quite a study; it would make an admirable illustration for a picture Bible. The palms which one admires so much from a distance; but grows so heartily sick of at closer quarters, have always a thickening of the stem, just above the ground, something like a big brown onion. This butt of the palm has several uses, all of them singular. The palm is cut off, some 10 feet above the ground, and the roots are trimmed off. It is then split up, and each half is hollowed. The result is two long wooden spoons, each some 10 or 12 feet long, and about two feet wide across the bowl. One use of these is as canoes, the natives sitting in the bowl of the spoon and balancing nicely so as not to upset and so as to keep the other end of the spoon well out of the water. He then paddles about the marshes, fishing. These same palm spoons, with slightly longer stems, are the basis of the irrigation system are far more primitive than the Egyptian water wheel. The spoon is fastened on a cross piece, working as an axle, and small quantities of water are then spooned up with it from the low level of the tank. A little higher up another big spoon is slung, which dips into a basin filled by the first spoon, and above this still other spoons, until a sufficient elevation above the field to be irrigated is reached. So, by indescribable labor, a small quantity of water is laboriously raised a few feet by the steady work of some half dozen men. Then the water, collected in the uppermost basin, is allowed to run along little channels and rills between the rows of mulberry plant; and this sort of thing is kept us all the time the plant is growing. One can understand a great many things from this. First of all, the dire calamity which follows, on a failure of the rains become more intelligible. So much of the agriculture of India depends upon irrigation, carried on through months with water accumulated in artificial ponds during the previous rain season. And the failure to replenish this accumulation means absolute ruin to all the crops, like rice, wheat and potatoes, but the plants, like indigo and mulberry, which the natives depend on to bring them the minute sums of money which are their sole connection with the finances of the world.

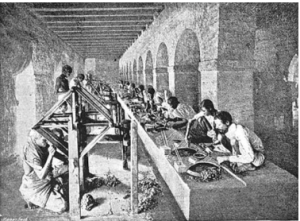

“Unwinding The Cocoons.[4]

When the mulberry plants are sufficiently grown the leaf bearing twigs are cut off with a knife, by hand, one twig at a time, and carried into the shed where the silkworms are kept. The silkworms are very particular and will only eat fresh-cut twigs, so that the supply of twigs must be renewed almost every hour. The amount of hand labor involved in this is something enormous, and after weeks of it the whole generation of silkworms may be destroyed by parasites. That helps to account for the look of world-weariness on the faces of the natives I met with the baskets of cocoons on their heads.

From being little black hair-like creatures the silk spinners gradually come to be thick, white and green worms, very repulsive looking, with voracious appetites, and a pungent, sourish odor, easily perceptible when a good many thousands are collected into a single room, as was the case in the Bengal Government’s building.

In course of time, however, their phenomenal appetites begin to fall, and they grow stiff and lethargic, and seem to shun human society. That is a sign that spinning time is close at hand, and is beginning of a metamorphosis which is presently to leave them as almond-shaped masses of the finest and glossiest golden-colored silk imaginable—the cocoon, to speak the language of natural history.

If left to unaided nature, this cocoon would go through a further transformation. The gentleman inside would presently turn into a small, brown, unattractive-looking moth, which would in time eat its way out through the silk, thus cutting across the yellow threads, and making it utterly useless for any human purpose. For Dame Nature herself has no use for the yellow threads so laboriously come by, and so Dame Nature must be frustrated, if Art is to be served. In other words, the gentleman inside the cocoon must be prevented in his attempts to metamorphose; and this is done by the simple though somewhat drastic process of steaming him to death. Then the silk is unwound off the cocoon, and being twisted up into great fat yellow skeins, is sold to the Calcutta merchants for transmission to the home markets, to be transformed into velvet and silk stuffs.

“Testing, Sorting, And Packing Silk.”[5]

It sounds simple enough to talk of winding the silk off the cocoon, but in reality, it is not so simple. In fact, it is very difficult. In olden times the natives used to put a handful of cocoons in a copper basin, with charcoal underneath, and the water, coming to the boil, gradually melted the glue with which the spinner inside had fastened his threads together. Then the women, who are employed in the filatures, catch up the loose end of the thread, which comes off the cocoon, and twisting some dozen of these threads together, fastened them to a diminutive spinning wheel, just like those which Gretchens of the Middle Ages used to spin their flax.

It is a pretty sight to see the native women catching up the almost invisible threads, thin as spider lines, and setting them on the quickly spinning wheel; though nowadays the charcoal embers are replaced by steam heat, and the wheel is set spinning by machinery. Throughout this whole process, and indeed until it comes into the hands of the dyers, the silk retains the gorgeous yellow hue which so delighted us on the heads of the time-worn natives, though I do not remember ever to have seen natural colored silk used in the arts, either in the East or in Western lands, to which silk has been coming ever since the days of ancient China. From the egg to the caterpillar; from the caterpillar to the cocoon; from cocoon to the boiling water and the spinning wheel—that is the history of Indian silk, and indeed of silk all the world over. There is an occasional variation, when a certain number of cocoons are set aside, and the moths within are given a chance to hatch out. These moths come forth, flutter their wings for a brief space in the upper air and then lay their eggs and die, and thus ends, only to begin, the silkworm’s strange, though uneventful history.[6]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES

[1] Alphonse Gallois stated: “The failure of the cocoon crop is principally due to the bad seed selected by the native breeders. Formerly they went to purchase seed from other districts and saw the worms spinning before buying their seed cocoons. In doing this they also rejected any bad cocoons. Now the system is for brokers, ‘Sanchoo Pikars’ go instead and buy indiscriminately and sell to rearers. The consequence of the absence of proper selection is that diseased and weakly worms are bred, the crop fails, and the rearers get disheartened. In those villages where the rearers have mud walled huts, the cocoons seldom fail […] Collective action is what is most needed to restore our silk industry, both at home and in India, and it is in my opinion, necessary that Government should take initiative in a well- thought-out application of any lever which will help raise so beautiful and artistic an industry to its proper and ancient proportions.” [“The Silk Conference At Calcutta.” The Civil & Military Gazette. (Lahore, Pakistan) January 12, 1886.]

[2] Anon. “Silk-Growing In India.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XLIII, No. 4. (April, 1897): 455-457.

[3] Anon. “Silk-Growing In India.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XLIII, No. 4. (April, 1897): 455-457.

[4] Anon. “Silk-Growing In India.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XLIII, No. 4. (April, 1897): 455-457.

[5] Anon. “Silk-Growing In India.” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly. Vol. XLIII, No. 4. (April, 1897): 455-457.

[6] Johnston, Charles. “Indian Silk.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) September 4, 1898; Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319; Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804.