WHO SOWS SESAME REAPS SESAME

Charles Johnston

February 1889.

The Nawab sent us one of his carriages, a big barouche with a fine pair of “Walers,” what we of Anglo-India call the big-boned steeds from New South Wales. Our kindly Muslim nobleman always sent for his visitors. And we, who helped to govern India, might, if need were, borrow a carriage, or an elephant or two, or a horse. But there must be no presents, save only fruit or flowers, no handfuls of sapphires, no tinsel slippers filled with gold mohurs and left under sofa-cushions, as in large days of old. The coachman, a proud Punjabi in a chocolate colored tunic, wore a button shaped turban, with gold lace. An equally proud footman sat up beside him. Two more held on behind, in like attire. They were to run ahead if there was a crowd and jostle wayfarers. That was oriental state.

The country round Murshidabad is a vast plain, level as the sea, whence, like disconsolate masts, rise fan-leaved palmyras and plumed date trees and coconut palms, whose stiff leaves glint in the sunlight, and send forth a crisp metallic tinkle, as they rustle in the wind. From the sun-flooded air come, ever and anon, the shrill, whistling cries of kites and buzzards, circling incessantly in the burning blaze of sunlight, while high overhead, like black specks against the incandescent blue, the vultures soar up in the eye of the sun.[1]

On a road like a red ribbon, with warm brick dust curling up behind the wheels, we whirled past the barracks, once tenanted by the fatal regiment among whom flamed up the Mutiny of 1857, ever since void of military occupants. There were fields on each side; rows of aloes and cacti by the wayside; here and there a bit of ragged forest, floored with clay and rank weeds. An acrid smell of warm damp came up from the woods, and flocks of white mist dragged across, above the trees, like the cloud messengers of Kalidasa. The country was a vast plain, level as the sea, whence, like disconsolate masts, rise fan-leaved palmyras and plumed date trees and coconut palms, whose stiff leaves glint in the sunlight, and send forth a crisp metallic tinkle, as they rustle in the wind. From the sun-flooded air come, ever and anon, the shrill, whistling cries of kites and buzzards, circling incessantly in the burning blaze of sunlight, while high overhead, like black specks against the incandescent blue, the vultures soar up in the eye of the sun.[2]

We sped along the wide road, rose red and set in Indian greenery, with plumed date-palms on either side, or fan-palms stark as bottle-brushes; the air hot as a palm house, quivering with the hum and whirr of myriad locusts, and sweet with the scent of yellow blossomed babul bushes. Our swift course brought us to the out skirts of Kasimbazar, where two centuries ago, Dutch, French, and English factors vied for Bengal silks; where, in a sad, unkempt cemetery, rest if rest they can so far from home, the wife and child of Warren Hastings, who was Resident here in Clive’s day.

Old English Cemetery, Kasimbazar.[3]

A hundred years ago Kasimbazar was a famed resort for merchants—the first mart, in all Bengal, famous for its silks and spices and all the luxurious commodities of the East. But one day the Ganges cut a new channel through the sand and left the wharfs of Kasimbazar high and dry, and the merchants went elsewhere and the city fell into decay. And now, after three or four generations, you can hardly find the traces of it among the trees.[4] Of the once vast city, naught remains but crumbling ruins smothered in Indian jungle. So swift is change in the changeless East. For weeks I had had a detail of work at Kasimbazar, visiting Maharani Swarnamoyee about a disputed land title.[5]

The red road was framed with the gold ribbed plumes of young coconut palms, with a backing of feathery bamboo thickets, and rich Bengal greenery. There was a sting in the sunlight when it flashed in your eyes from a lotus pond; something malignant, that suggested elemental demons.

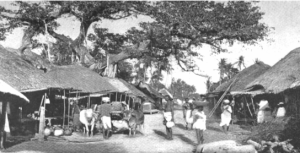

Nizamat Stables.[6]

A white road crossed the red one, on either side into the wilderness. Then more fields, more palm trees, more aloes; more eagles, shrilling and shrieking above us in the sunlight. Then a long, dusty interval. Then a halt. We were to change horses at the good Nawab stables, some two miles off on the road to Berhampore. We reined up amid a padder of dusky grooms; and a second pair of fine “Walers” took the place of the first, foam-lathered from their eighteen-mile rattle through heat. All four Punjabis shouted and bustled and gave orders. Four more came out and helped, shouting, and bustling and giving orders. Then two thin and humble Bengalis came and did the work. And once more we started.

Verochka jumped, and pointed under the trees. Eugène jumped sympathetically, and said, “Oh!” in a tone of alarm. And we all looked. For, while on one side of the road there was commodious housing for two or three dozen horses, on the other His Highness’s two score and ten huge elephants, in various attitudes of unconcern, were anchored, like enormous gray boulders, in a mango-grove by the way side. They cheerfully munched vast quantities of grass and straw and roots and leaves, chewing the cud of reminiscence, tiger hunts, where one or the other was scarred and furrowed by poisonous claws; or famous pig-sticking parties, where a big boar escaped, even after two spears had crossed each other in its body. Big-eared giants, trumpeting hilariously, with the sound exactly like a chain-cable being lowered from an iron hawse-hole; whereat the horses grew hysterical, gibing under the hand of our masterful Punjabi.[7]

Our journey’s second stage was briefer. We soon reached Murshidabad, the old famous city not far from the head of the Ganges delta, hidden among long-plumed coconut palms and glossy mango trees. Murshidabad, once the chiefest in Bengal. Here dwelt the Mogul princes from whom Clive and Warren Hastings wrestled the richest province of India; and here dwells still, in the hushed and pathetic peace that rests on fallen rulers, the last representative of a line that once held sway over a land as rich and populated as France, and far older in renown. The city had once nearly a quarter of a million inhabitants, yet you can drive through it, from end to end almost, without seeing city at all. So swathed is it all in gardens, mango groves, and palm fringed avenues that it looks more like a greenhouse than a city. [8]

Among the dense groves of palms and mangos, in their unbroken greenness from the river bank, yellow with scented mimosa blossoms, to the great road that goes southward towards Plassey, Murshidabad lies, completely hidden, so wreathed were all things in gardens and trees. It was betrayed only by the howl of a pariah dog, or the blue smoke, keen and acrid, that rises from some native hearth. Only coconut palms and groves, and long discolored walls faded stucco.

So many of the buildings in Bengal have the same long structures of withered antiquity, but many of them are not really old. The reason is this: The whole of lower Bengal was laid down by the Ganges in year after year of flood. Consequently it is all sand and there is not a stone to be found through the length and breadth of the delta and all the districts that border on it. So the only building material is brick, and very poor brick at that, always crumbling away under the stress and strain of the tropical heat and rains. And getter to preserve the brick inhabitants cover their buildings with stucco and this again with various distemper washes or sometimes simple whitewash. Now the rain beats down on this stucco and the sun bakes it, and then again comes the rains and very soon it is blotched and bleared and faded into a hundred shades of withered age. So that every building gets discolored and old looking, even after a few years. Then there is another element of destruction. The winds bring seeds from the jungle, from the banyan trees and the India rubber trees and the date palms and a dozen more nameless lords of the forest. And these seeds, settling in any niche or crevice of the building, soon begin to sprout and grow, striking their roots in between the bricks as trees strike root in a cliff. But brick walls are not cliffs, and so the trees soon ger the better of them and the jungle wins its own once more.[9]

Murshidabad might be passed unseen, for all its score of thousand inhabitants, whether from the river or from the inland tracts, were it not for the clustering buildings that have grown up around the Nawab’s palace. We did, it is true, pass through one brief line of shops, where, propped up with bamboos, little open booths, under thatched screens, were piled brass water-pots, or strange-hued fruit and vegetables, or big red earthen jars, or bales of Madras muslin and Kashmiri cloth. There was a crowd of natives in the distance, Mussulmans by their caps, jackets, and beards. A man who shaves has ninety-nine gods; a man who does not believes in Allah alone.[10]

The grooms hopped the ground, and ran ahead through sparse crowd of Bengalis, shouting “Kabardar!” which meant, from its practical effect, “Make way for your betters!” and little brown naked kiddies scurried away before them. A gray cat, just escaping, was caught up by an old woman with a mahogany face framed in white hair, who hugged it lovingly and made fiendish grimaces at the too headlong grooms.

“A huge banyan tree overshadowed a group of native huts: straw sheds propped up with bamboo.”[11]

“She loved her biral and her biral loved her!” pensively murmured Eugène, half thinking in Bengali, as we swung round to the right, under the arched guard-house, and entered the enclosure of the palace. A dozen little soldiers of the Nizamat army, bare foot and beltless, were lying about, luxuriating in smoke, dreamily singing an Urdu war song.[12] They dropped their hookahs, suddenly, as we swung into sight, and wriggled up like beetles, trying to get their belts on and salute at the same time. We were out of sight before they managed either. From eating much rice, they grow tender round the waist, and their belts gall them. So they wear them only when saluting, or on the march till they get round a corner. I knew those little soldiers intimately.[13] The Nawab draws a pension of 240,000 rupees a year. It fell to me, as part of my duties, to count his count his monthly installments, and hand them over to this little army of twelve soldiers which he sent every month, with a bullock wagon, to the district treasury. The dark-faced little soldiers, with their red turbans and bare feet, marched up solemnly and stand at attention outside the treasury door, while the little bags of rupees, a thousand in each bag, were put in a packing case, and hoisted on the cart. Then the twelve little soldiers saluted gravely and started up the road, going fully two miles an hour, in the company of the slowly crawling bullocks.[14]

Elephant with umbari at the Nizamat guard-house.[15]

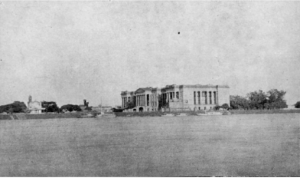

Then passing a wide barren lawn drew up under the high porte cochère our journey’s end. The proud Punjabi put on a magnificent spurt as we came to the home stretch. It is a point of honor with the native horseman to stop much quicker than he goes on. The huge palace, that towers over the Bhagirathi river, rose before us with a broad blue stretch of Ganges in the background a huge building, with Corinthian pillars, architraves, pilasters, and all the rest of it, five stories high, and all stuccoed copper color. A whole swarm of little palaces surrounded it, in which dwell his brothers, his mother, his sisters, his cousins and his aunts.[16] Curiously enough, though we have here a little kingdom of the Arabian Nights, with veiled beauties, Abyssinian eunuchs, dark eyed dancing girls lunatical, turbaned priests, and all the glories of Scheherazade, still the palace itself suggests nothing of all this, being a stately columned building in the style of the Italian renaissance suggestive enough of Naples and the gardens of Pausilippo, but, outwardly, at least, utterly detached from India.[17] Verochka said it reminded her of St. Petersburg, which is, indeed, equally outlandish. The palace was built for the Nawabs by the British Raj, in a day of less instructed taste.[18]

At the door beneath the grand staircase we were met by Fazl Rubbee, His Highness’ private secretary. He was a really magnificent man, six feet high, like a bronzed eagle. He wore yellow satin, and a turban like the sun. He guided us up the stairway adorned, in admired confusion and barbaric luxury, with spears, tiger skins, boars’ heads, elephants tusks, and Afghan weapons. There were also little Greek goddesses in white marble, which drew the eye of Eugène. They were comfortably clad for the Indian heat.[19] The corner Rubbee’s eye lingered lovingly on the most dangerous of the three. Also Eugène’s.

The Palace from Roshinbagh.[20]

And so we reached the chamber of the presence: a vast pillared drawing room, with tapestry punkahs hanging from the beams; which punkahs promptly began to sway as we entered.[21] Rubbee invited us on behalf of His Highness, to “partake of a light refreshment, after our fatiguing journey.” The courtly politeness of the East affected to believe us as weary and dust-worn as a green turbaned Haji from Mecca. The kind-hearted Nawab, though a staunch Mussulman and a rigid abstainer from wine, was benevolent enough to treat us with less stern asceticism, as testified by some dark-green bottles with golden knobby corks, reposing peacefully in a pall of ice—ice that had traveled twelve score miles under the burning Indian sun.

As Eastern etiquette ordains, the Nawab himself was not present while we “partook of the refreshments,” to use Rubbee’s phrase, in the lofty chamber with painted roof upborne on pillars, and walls hung with portraits of some gold-decked Indian prince or warrior, or dreamy landscape full of mosques and palm-trees, wrapped in the amber haze of the Orient. The great reception rooms, with their ivory inlaid couches, Brussels carpets, Belgian crystal chandeliers, and vases of Bohemian glass, are marked by only a few Indian traits, the portraits of former Nawabs, in splendid robes, heavy with gold and jewels, every button a large emerald, while table diamonds, as large as a lady’s fingernail, appear as additional adornments, armlets, loosely fastened above the elbow, or brooches holding an aigrette of stones, that twinkle like dew drops in the purple fez of these Shia princes.[22]

“The Chamber of the Presence.”[23]

So, watched over by Rubbee, we quaffed the cooling “simpkin,” as the Indian servants have christened the airy fairy liquor of the sunny champagne hills. Then, when in Homeric phrase, we had removed the desire of eating and drinking, we were conducted, still with the courtly ceremony of the East, to the state reception room, and felt among couches and ivory and vases of alabaster to await the arrival of His Highness, the Nawab.

Indian Figurines (Murshidabad)[24]

While our eyes were wandering among rare inlaid cabinets and cages of gold and ivory, a solemn hush fell upon the yellow-turbaned servants, announcing the approach of the descendant of the old viceroys of Bengal. A bronzed, stately man, rather small and stooping, and looking greyer and older than his years, a face full of gentle kindness, rather than power, and with the indescribable courtly charm seen only among the ancient aristocracies of Asia, a charm that may quite well hide, and often does, a wild ferocity and recklessness of human life that only the untrammeled despotism of Asia could give birth to. But there was no hidden ferocity or blood-hunger in the languishing, velvety eyes of the good grey prince.[25] He was no fierce Timur, or ensanguined Nadir Shah, but the simplest of noble men in plain white muslin and a purple fez, a thimble shaped cap with an aigrette of heron feathers.[26] His was a gentle courtesy, half regal and half timid, and refinement of hospitable urbanity that only the East understands. [27] His brow, eyes, and nose were Persian, but his lips had something Ethiopian about them, heavy as in the statues of Rameses. There was a story among the ladies of the station that those were the lips of an Abyssinian beauty who danced into the of the late prince.[28]

The good prince, slightly stooping, began to show us his treasures: a picture by Vandyke, some English cavalier roasting out here for his sins; then Lord Cornwallis, in scarlet uniform; then to an ornate portrait of his father, a magnificent and kingly Oriental, with eye like an eagle, and dight with gold lace and many decorations. A right fierce spirit, one would say, this Muslim squire of dames; far more warlike than his quiet, gray-haired successor, whose slight figure, all in white, stood in marked contrast to the great warrior. We sat down beneath the portrait of his father, Nawab of all Bengal, who rivaled the old days of Haroun Al Rashid in the largeness of his heart, and its ever changing joys.[29]

(Left) Nawab Nazim Mir Mahomed Jaffer & His Son, Nawab Mirzan.[30] (Right) Nawab Nazim Sayyid Mansur Ali Khan.

Eugène touched Verochka on the elbow and said something in French. I have a conviction that it was about the late prince, who was a gallant gentleman in every sense, and left a number of stricken widows. His present highness refers to them all respectfully as his mothers. I can guess which of them Eugène was telling about. Verochka said, “Hush!”[31]

We sat down beneath the portrait, and the conversation turned, I know not by what gradations, to religion. The Nawab, a Shia by faith, and therefore inclined to toleration, declared that he was imbued with the idea that all religions at heart are one.

“Still,” he said, “there are deep differences. It seems to me,” he went on, with gentle seriousness so characteristic of him, “that Christianity has been the better religion for women; my own has been better for men. What ideal of manliness the Prophet’s faith holds up. Think of the Osmanli Turks or the Arab Sheiks, or our own Moguls—all devotedly religious. A virile faith. But the religion of Jesus has always been wonderfully tender to women and children, and I think today your churches are built on the hearts of women; but your leading men, in politics or science or literature, seem to me to be estranged from Christianity. It does not hold their intellects as it holds the hearts of the women. But, of course, I speak as a stranger, and really know very little of these things. For my own part, I think that Buddhism attracts me more than any other religion. There is such a spirit of gentle charity through all Buddhist history—no religious wars. I have been reading Edwin Arnold’s book, and it appeals to me, ‘he who sows wheat reaps wheat; who sows sesame reaps sesame.’[32] The understanding of that should reconcile everyone to his place and lot. And then, most of all, it holds out such a beautiful ideal of final peace; perfect ceasing from all sorrows, freedom from the last remnant and memory of ourselves, in Nirvana, where the Silence reigns!” And the good prince became silent, with a far-away look in his eyes, as one who was infinitely weary of the burden of being, and full of immeasurable longing for the Beyond.

“Buddhism is the true Oriental religion,” he went on; “we, who are genuine Orientals, have in our blood the feeling of the great Nirvana, the brooding stillness and peace. You Westerns are frightened at it, and long for strife. We long for rest.

Eugène sat with a slight smile of gentlest irony. One suspected of being a Voltairean at heart, full skepticism concerning these high matters. But with a Frenchman’s pretty politeness, he said nothing, contenting himself with that little ironical smile.[33]

His highness showed me some French Empire cabinets, with old Bohemian vases in them, sapphire and ruby enamel laid over clear glass, and then parts cut away with a lapidary’s wheel. Then came a gilt clock under glass, that was to ring a chime or do something, but missed fire. The prince was showing me some delicate ivory carvings little elephants with punctured lace trap pings bullock carts marvelous chess men in Persian armor—when the lady of the party evidently prompted thereto by Eugène, came forward and asked his highness with how many brothers he was blessed. Eugène hung about in the background.[34]

Verochka, who was born in the Caucasus amid Georgian and Circassian dignitaries, and so had a happy way with Oriental princes, took us all aback.

His Highness looked at her with a queer little smile, half tolerant, half amused, and began, with great show of seriousness, to count them on his fingers, first of the right hand, then of the left; after going once or twice round, he halted, started again, then stopped and said—

“I am afraid I must ask my secretary.”

Rubbee replied, with dignity, “Your Highness had a hundred and nineteen brothers!”

Verochka, no whit abashed, then asked this good Oriental nobleman concerning his sisters.

He smiled very charmingly, saying, “I am afraid I do not know; we never counted them!”[35]

Which reminds one of those Biblical reckonings besides women and children.[36]

Then we went to the library, a vast room high up, and stretching from end to end of the palace. The view from the windows opened out for miles; blue rivers, green jungle, red roads, white temples, the sun flooding them all with gold.

Across the river was the Kushi Bagh, “the Garden of Gladness.” There the ancestors of the nawabs all lie entombed in white mausoleums, among trailing roses and hibiscus with scarlet trumpet flowers. There gorgeous butterflies flaunt their velvet wings. There croons the bulbul to the moon. There quiet dwells. The princes rest amid the greenery and blossoms and listen to the throbbing of the river, awaiting what time the Lord of the faithful shall call them to rise and enter paradise, where dark eyed houris shall greet them with long languishing lashes, songs that still all sorrow, and honey scented lips.

Among the notable things about the palace are the collection of Oriental illuminated manuscripts, chiefly Qur’ans, centuries old, on delicate textured vellum; and the great poets of Persia, Saadi and Hafiz, Jellaladdin and Firdusi, or Omar Khagan and a score of others, sweet singers in the sweet Oriental tongues, and as courageous in the color of their verse as these manuscripts now are in the rainbow tints of the illuminators of Tehran. They were written in the graceful Arabic characters in tracery like old lace across the pages; and gold and red and purple added their brightness to the scrolls.[37]

The good prince loved these things. As he turned over the enameled pages tenderly, he read out here and there a verse or a single ringing line. Then he began to recite a few of his favorite passages, a little shyly at first, then with growing enthusiasm and warmth; intoning the lovely Persian ghazals with their long, lingering rhymes and deli cate melodies like soft echoing music, until his spirit was rapt into paradise and saw once more the glad days of Iran and evoked the courtly singers from the shades to crown the wine again with roses and breathe the beauty of the east, with all its languorous fascination.[38]

Besides these Eastern splendors, the great volumes of steel engravings, all by famous men, that heap the library tables, are of little interest. What we seek is the voice of the East, not the mere echo of the West. [39]

The quiet hours sped; the good Nawab nourished us; the time came for our return. Once more we found ourselves in high-swung carriage with the masterful Punjabi in command. Evening was descending upon us; the mantle of clouds had rolled away, and there were transparent spaces of light, gradually growing dim and spiritual. Crickets began their whirring refrain, in the grass, from the stems and branches of trees, till the world throbbed with their pulsations. The air was drowsy, the wind as a zephyr of paradise, gently swaying the dark, ferny arms of the palm-trees shadowed against the dying glow the sky. Then, as we sped swiftly on, came darkness; and, with darkness, the stars—great, colored jewels, standing forth, as it seemed, from the purple of night; the benign air, and darkness, and the crickets’ song.[40]

Eugène was gladdening Verochka’s heart with the gossip which she so frankly enjoyed. They were whispering again. It was about another romantic tale of the palace; a disputed succession this time. No great marvel, when you come to think of it, among five score brothers. Where many ladies are involved interesting questions, precedence must arise. One might make a Mussulman or Mormon novel out of that.[41] In this particular case the prince of the blood was ousted by son of the Abyssinian, whose twinkling feet played havoc with the heart. The lady mother of the was a princess from the sunny lakes of cool Kashmir, with their plane tree isles reflected clear, as the poet says. She was proud and very beautiful, and had a large dowry and perfectly sapphires. Her son was also proud very beautiful, and in course of time grew up to be, like his father, a gallant gentleman in every sense.[42]

“His late Highness, ah, madame!” Eugène said, with pretty French gestures and smiles, “his late Highness was galant homme et homme galant! He shared the tastes of Solomon—il avait les goûts de Salomon, sans avoir sa sagesse! The good Prophet Mahomet, chère madame, recognizing the irresistible sweetness of the ladies, permitted his followers to take four charmers in lawful wedlock.”

Verochka declared that she could sympathize perfectly with that, and could not see why it should not be extended to husbands, so that one might have one for each mood.

Eugène shook a reproving finger.

“His late Highness,” he resumed, “obeyed the ordinance of the Prophet; in his zeal, he even exceeded it—by some dozens. There was a lovely princess from the Vale of Kashmir, with long, languishing eyes; there were other Indian brides; there was a wildly enthusiastic Englishwoman, whom His Highness gathered in from a small hotel in a London suburb, and who, when overwrought, enforced her conjugal persuasions with a riding-whip or a pistol; two of her daughters are growing up in the harem now; and there was an Abyssinian girl—a dark, lithe, smiling beauty,” went on Eugène, “who danced her way into his late Highness’s not unsociable heart. And do you know, madame, her son turned out to be the wisest of them all; and when the old Nawab died, full of years and progeny, the British Government chose him to succeed, and inducted him into all the glories of the Nizamat.”

Verochka’s lips framed a question. Eugène mysteriously nodded, and pressed his finger to his lips. “On le dit, au moins, madame!”

He went on to say, still with little shrugs and smiles, that there was fierce Oriental jealousy between the brothers. Sultan Sahib, the son of the Kashmiri princess—a charmingly handsome gentleman whom we knew very well—held that he, and not the child of the Abyssinian beauty, should have been heir to the Nawabs. It was whispered that he had never forgiven his brother, and so lay in wait for the incumbent, seeking, in default of beer, which is forbidden to pious Mussulmans, to put poison in his sherbet; knowing which, the elect brother tasted no food but what his own faithful cooks had not only prepared, but had also tasted themselves. Isaac and Ishmael reversed.[43] All of which I recount, not to approve the habit of gossip, but to characterize Eugène.[44]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897.

[2] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897.

[3] Walsh, J.H. Tull. A History Of Murshidabad District (Bengal) : With Biographies Of Some Of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 78.

[4] Johnston, Charles. “Mussulman Festival.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) December 4, 1898.

[5] [Johnston, Charles. “How The Army Was Kidnapped.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXIV, No. 4. (October 1914): 469-477.] At the time of Johnston’s arrival, Swarnamoyee was in the process of finalizing her purchase of an estate known as Mouza Hatzore. “[Swarnamoyee] brought her expertise in Revenue sale proceedings to increase her properties there. Ballia no longer remained an island but joined the mainstream of administration. On 20 March 1876, Swarnamoyee bought in Revenue sale the Ganeshpur zemindari for Rs. 50, Mouza Sabeya for Rs. 50, mahal Narayanpur for Rs. 20, mahal Bhagwanpur for Rs. 10, mahal Patishai for Rs. 15, mahal Tajpur for Rs. 25 and mahal Gopalpur for Rs. 25. Thus for Rs. 195 she acquired rights over a troublesome group of tenants, who in spite of their bad reputation never defaulted her payments which was about Rs. 1000 per annum. On 20 November 1878, she bought Hatzore zemindari in Revenue sale for Rs. 11,000 in spite of the stiff opposition of the neighboring zemindars who had been shaken out of their slumber by her since 1876. Swarnamoyee however felt that the bad feeling of the surrounding zemindars might create difficulties for her administration as she would be living 500 miles away. She therefore did not purchase any property for some time, coming back suddenly to buy the rest of Mouza Hatzore, in Revenue sale on 4 March 1889 for Rs. 2474- 6-6. which consolidated her position, She also bought in Revenue sale the zemindari of Bansdih on 29 June 1889, for Rs. 462, for which she had to go a little further and deeper into the Muffasil.” [Nandy, Somendra Chandra. History Of The Cossimbazar Raj Vol. 1. P.K. Roy. Calcutta, India. (1957): 452-453.]

[6] Majumdar, Purna Chundra. The Musnud Of Murshidabad (1704-1904): Being A Synopsis Of The History Of Murshidabad For The Last Two Centuries. Saroda Ray. Murshidabad, India. (1905): 168.

[7] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897; Johnston, Charles. “Mussulman Festival.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) December 4, 1898.

[8] Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.

[9] Johnston, Charles. “Mussulman Festival.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) December 4, 1898.

[10] Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.

[11] Johnston, “Prince of India,” 309-319.

[12] Johnston, Charles. “How The Army Was Kidnapped.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CXIV, No. 4. (October 1914): 469-477.

[13] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897; Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804.

[14] Johnston, Charles. “Mussulman Festival.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) December 4, 1898.

[15] Majumdar, Purna Chundra. The Musnud Of Murshidabad (1704-1904): Being A Synopsis Of The History Of Murshidabad For The Last Two Centuries. Saroda Ray. Murshidabad, India. (1905): 200-201.

[16] Johnston, Charles. “Mussulman Festival.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) December 4, 1898.

[17] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897.

[18] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897; Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804.

[19] Johnston, Charles. “Mussulman Festival.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) December 4, 1898.

[20] Majumdar, Purna Chundra. The Musnud Of Murshidabad (1704-1904): Being A Synopsis Of The History Of Murshidabad For The Last Two Centuries. Saroda Ray. Murshidabad, India. (1905): 200-201.

[21] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897.

[22] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897.

[23] Johnston, “Prince of India,” 309-319.

[24] Tallis, John. Tallis’s History And Description Of The Crystal Palace, And The Exhibition Of The World’s Industry In 1851, Vo. I. John Tallis And Company. London, England. (1852): 132.

[25] “A Nawab’s Jewels.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island) August 30, 1891.

[26] Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804.

[27] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897.

[28] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897.

[29] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897.

[30] Walsh, J.H. Tull. A History Of Murshidabad District (Bengal) : With Biographies Of Some Of Its Noted Families. Jarrold & Sons. London, England. (1902): 150.

[31] Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.

[32] “That which ye sow ye reap. See yonder fields! The sesamum was sesamum, the corn was corn. The Silence and the Darkness knew! So is a man’s fate born.” [Arnold, Edwin. The Light of Asia. Trübner & Co. London, England. (1879): 219.]

[33] Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804.

[34] Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.

[35] In “A Prince Of India,” Johnston writes: “The prince in all simplicity began to count on his fingers. He went over both hands twice; then hesitated; then tried again. Their names sounded like Omar Khayyam in the original. At last he called his private secretary, and referred the problem to him. My memory of the answer is something over a hundred. But I will not dogmatize. Sisters did not count. Even the secretary did not keep check of them. The late prince was a gallant gentleman in all senses.” [Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.]

[36] Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804.

[37] Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.

[38] Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.

[39] “An Indian Prince.” The Providence Journal. (Providence, Rhode Island): September 12, 1897.

[40] Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804.

[41] This reference to Mormons here would have been obvious to Johnston’s contemporaries in the late 1880s. Just weeks before Johnston left for India, in July 1888, Arthur Conan Doyle published a book version of A Study in Scarlet, which featured the debut of his popular character, Sherlock Holmes. If Johnston did not read it, he was certainly aware of its themes, as he states that he was “captivated by the magic of the great modern detective stories.” [Johnston, Charles. “The Detective Story’s Origin.” Harper’s Weekly. Vol. LIV, No. 2773 (February 12, 1910): 16, 34.] A Study in Scarlet belonged to that late-Victorian subgenre, “imperial gothic,” which used the theme of nefarious forces from the colonial periphery invading the home country. In the story, Sherlock Holmes is compelled to solve a mystery to the backdrop of Mormon polygamous intrigue. It followed in the wake of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1885 tale, “The Story of the Destroying Angel,” the themes of which drew parallels between the perceived failure of Mormons to respect the American boundaries, with their failure to respect the boundaries of matrimony and domesticity. Though A Study in Scarlet was not without sensationalism, Doyle was decidedly more sympathetic of the Mormon enterprise. Being a vocal champion of what he termed “the [future] claims for the English-speaking race all over the globe,” Doyle used the story to praise the virtues of the Mormon project. The Mormon Prophet, Brigham Young, built a thriving civilization where once there was inhospitable wilderness: “Maps were drawn and charts prepared […] In the town, streets and squares sprang up, as if by magic […] Above all, the great temple which they had erected in the center of the city grew ever taller and larger.” [Lecourt, Sebastian. “The Mormons, the Victorians, and the Idea of Greater Britain.” Victorian Studies. Vol. LVI, No. 1 (Autumn 2013): 85-111.] Though polygamy was regarded as a sexual taboo, many of those polygamous husbands and wives had emigrated from Britain. Thus, Mormonism was, in a sense, both foreign and familiar to the English. Mormonism undoubtedly defied Victorian convention, and most agreed that it was “heathen,” but it could not confidently be classified as “non-Christian.” Beyond its appeal as a masterful work in the detective fiction, Doyle struck a nerve in his readership by using A Study in Scarlet to address two great anxieties which threatened public and private spheres alike. The first anxiety was the growing paranoia of a “state within the state,” which Doyle invited his readers to examine by projecting these fears onto Utah; a “state within a state” governed by the liminal-English Mormons. By indulging in the horror directed upon the Mormons, the English reader was also allowed to explore the inevitable horror that would, in due course, be visited upon them. [Fillingham, Lydia Alix. “’The Colorless Skein of Life’: Threats to the Private Sphere in Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet.” ELH. Vol. LVI, No. 3 (Autumn 1989): 667-688.] Would Britain share the fate of the city in Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!” The same month in which A Study in Scarlet was published, the Conference of Bishops in communion with the Church of England discussed “polygamy, especially in its relation to those other races and nations with whom [they were] brought into contact in [their] own colonies and in foreign countries.” The Select Committee unanimously declared: “The sanctity of Marriage as a Christian obligation implies the faithful union of one man with one woman until the union is severed by death. The polygamous alliances of heathen races are allowed on all hands to be condemned by the law of Christ.” [Richard, A.P. Marriage And Divorce. Trübner And Co. London, England (1888): v.]

[42] Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.

[43] In “A Prince Of India,” Johnston writes: “The scion of Kashmiri kings saw the son of the Abyssinian preferred to him; Isaac and Ishmael reversed. And a terrible rivalry arose between them so that the young prince felt the shadow of the chosen heir darkening the sun against him, and compassed about how he might slay him. So [Eugène] said. He may have read it or made it up.” [Johnston, Charles. “A Prince Of India.” The Puritan. Vol. V., No. 2. (March 1899): 309-319.]

[44] Johnston, Charles. “His Highness The Nawab: Helping To Govern India.” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. CVIII, No. 4. (December 1911): 797-804.