ANGLO INDIA

Tuite-Dalton took his leave of absence in late-February/early-March. His replacement, John Gerald Ritchie (1853-1921,) soon arrived with his wife, Margie, and their infant daughter, Theo.[1]

John Gerald Ritchie (1853-1921) was born in Calcutta. The son of William Ritchie, Advocate General of Bengal. In 1859, his mother took him and his brother back to Europe, where they lived with their aunts in Paris. In 1862 he entered a private boarding school, Whitnash Rectory, Warwickshire, and then Winchester School from 1866-1872. In 1873 he passed the entrance examinations for the Indian Civil Service. He took a two-year course in law, political economy, Indian history and three Indian languages at Trinity College, Cambridge.[2] In 1875 he sailed to India, and in 1882 he married Margie Thackeray (1863-1944.)[3]

Margie’s father, Sir Edward Thackeray, who retired from military service in 1888, was an eyewitness to the 1857 Sepoy uprising in Murshidabad.[4] The son of Reverend Francis Thackeray, Edward Thackeray was the first cousin of novelist William Makepeace Thackeray.[5] Another cousin, Colin Shakespeare, whose tomb was in the Berhampore Cemetery, was said to be the inspiration for John Sedley in Thackeray’s novel, Vanity Fair.[6] When Margie’s mother died in 1864, Anne Thackeray, the eldest daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray, adopted Margie and her sister.[7] In 1877, Anne Thackeray married Gerald’s brother, Richmond Ritchie, making Margie her distant cousin, adopted daughter, and sister-in-law.[8] A gifted writer like her father, Anne Thackeray’s 1885 novel, Mrs. Dymond, introduced the proverb, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for life,” into the English vernacular.[9] Her 1887 short story, “Little Esmé’s Adventure In The Strange House,” was dedicated to Theo Ritchie (John and Margie’s daughter,) who was born that year.[10] The following is a selection from John Gerald Ritchie’s memoir (written to his daughter, Peggy,) which gives some extra insight into the India the Johnstons encountered.

~

EXCERPT FROM JOHN GERALD RITCHIE’S MEMOIR

1887-1888

And now I come to the year 1887, when our Theo was born, and life was transformed for us by her presence. In the hot weather I officiated at Howrah for three months, my first independent charge of a district. Howrah corresponds to the Surrey side of the water in London. It is a busy region of jute-mills and iron-works and much hammering. The magistrate’s house was set in the midst of all the din, and near a noisy railway-siding; but, in spite of the noise and the smuts, we liked the great double storied house with its long verandah, getting the breeze off the river. We used to drive into Calcutta; but the best place in those hot days was the bridge over the Hoogly, from which there was a great view of the shipping and the cool draught always blowing across. Theo was born on June 7, in the late evening. The weather was very hot and sultry. I had returned opportunely from an inspection tour. I paced the verandah that sultry night in great anxiety. The constellation Scorpio was in great glory in the southern sky. She was christened Theodosia by our Padre, Mr. Rolfe, in Howrah Church. Your mother’s dear old ayah, Bifātan, became Theo’s nurse, and was very proud of her charge. This ayah was a quaint, sensible Mahommedan up-country woman, with a head resembling that of Savonarola. She wore trousers in the up -country fashion, and regarded your mother as her child. It was great fun to see her with Theo, squatting and talking to her in the sagest way. She continued most devoted to our family, and to the last communicated regularly with us.

Sir Steuart Bayley had become Lieutenant-Governor and was at Barrackpore, from which he came over to see us and took us out in his launch. I completely fail to understand why the Bengalis clamor for a Governor from England. It wants great knowledge, not only of India but of the particular province, to enable a Governor to do good, useful work. We civilians know that we are only beginning to understand our adopted country as we are leaving it for good. The English-bred Governor has no notion of what he has been sent out to do. His public utterances are absurd. We had great statesmen from Bengal for Governors since 1854,when it was first created a separate charge. Frederick Halliday, John Peter Grant, William Grey, George Campbell, Temple, Rivers Thompson, were a fine succession. Sir Steuart Bayley, then in the prime of life, was the son of a civilian who had acted as Governor -General. He had served continuously without furlough for twenty years, and was honoured and respected by the leading Bengalis. To compare with such a man the average peer or M.P. was ludicrous.

There was an absurd Government rule giving sixpence to every man who satisfied the district officer that he had killed a poisonous snake. Snakes are regarded by some as divinities, and, as no cultivator in his senses would care to spend a week in dancing attendance at court to get a reward of sixpence, there was scanty response to the Government offer. But one ingenious individual, seeing that an honorable livelihood was to be gained from the sirkar’s coffers, bred poisonous snakes in considerable numbers and used to come in with a large basketful periodically to destroy before the magistrate and—go home with the reward. My Calcutta friends used to come over, when they heard that the snake-charmer was expected, to study every variety of poisonous snake before they were whacked on the head and demolished. Then the pied piper would retire to his out-of-the-way hut (nobody could find out where he lived)and go on with his interesting snake-culture. From Serampore I went to Alipore as magistrate for three months. The house and garden, which were occupied by my great-uncle, Richmond Thackeray, from 1811 to 1815, were pleasant.

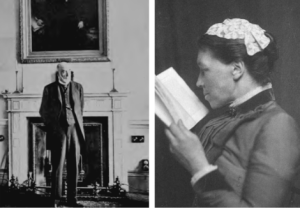

( Left.) Margie Ritchie [1866-1869.] (Right.) Margie Ritchie as an adult.[11]

I remember taking Theo in my arms when she came down from Darjeeling, and her smiling, and smiling away at me, for the first time clearly recognizing her father. She continued to smile at me the rest of her life.

I had an amusing little piece of duty at Chandernagore. Our authorities were much exercised at the conduct of the French officials. A bailiff sent to execute the process of the British Government against a debtor had been seized and imprisoned on the pretext that he had over stepped the boundary and had acted illegally on French soil. The matter went up to the Indian Foreign Office, and I was deputed, with much formality, to inquire. I went to Chandernagore and met an effete French colonial official, the juge de paix, old and yellow. He was delighted to let me take the whole matter in hand, examine the witnesses, and write the report. The settlement had been left in charge of an uppish youth who had been playing pranks. I unraveled this tangled skein in diplomatic language and in excellent French, the result of a confabulation with the Buckland’s’ French governess, and the old juge was only too happy to append his signature. We sealed the treaty over an excellent dinner en famille with his large colonial family. The following day I set off for a fortnight’s trip to Rangoon. I stayed with Jack Lowis, a barrister friend, and fell in love with the great Pagoda, the Shwey Dagon, and the Burmese.

(Left) Gerald Ritchie.( Right) “Gerald Ritchie And Richmond Ritchie During The Mutiny In Volunteer Uniforms Asking A Disarmed Sepoy At Barrackpore Where His Gun Was.”[12]

On the voyage back we had an absurd German Grand Duke and his suite among the fellow passengers. He and his party sat away from the other passengers during meals. For his delectation after dinner a loud mechanical organ was set to work by one of his henchmen.

Howrah District is cut up by rivers, and we had some travelling in a house-boat that cold weather, with the bairn. We combined this with Calcutta sociabilities. I remember returning unexpectedly from camp, going to bed, and being awakened at 2 a.m. by my wife’s poudrée head, returning from a ball.

At the beginning of the hot weather I was delighted to hear from Edgar, who had become Sir Steuart’s Prime Minister, that he was sending us to Darjeeling. I was to be Inspector-General of Registration, a travelling appointment with liberty to come to Darjeeling for some months. I took the family up to Darjeeling at Easter. Theo was an excellent little traveler, and the only thing she minded was the hooting of the steamer’s whistle. An absurd contretemps occurred on the journey. I got into the wrong carriage at Sara, and was whirled off to the dismal station of Rungpore while they went to Darjeeling. I lost one of my precious three days.

We were in despair at the prospect of a boarding-house to leave m y wife in. But the difficulty was solved by an invitation from the Jarretts to share Little Chevremont with them. This proved a most satisfactory arrangement. Colonel [Henry Sullivan] Jarrett, a cultured man, who translated Heine, was filling the position of Examiner in Eastern Languages.[13]

Their jolly, fat little boy, Aubrey, played with Theo, who called him ‘Auby, Auby.’ Theo developed into the softest, most winning little thing, with her ‘coos’ and white, fluffy hair. She was always smiling, and excited admiration as she was wheeled about in her pram.

The Sikkim Expedition was going on, a mild warfare against the rudely armed Tibetans, who had taken alarm at a proposed mission and built a wall across the Jelepla trade route. Our troops were encamped at Gnatong below the pass, which I had visited. Sir Steuart Bayley paid our troops a visit, and on the same night the Tibetans made an attack, perfectly ineffective. On fine days Darjeeling could heliograph 100 miles to Gnatong. Soldiers in khaki going to the front were to be met on the forest roads.

The Shrubbery or Government House was a pleasant house in those days. We had Shakespeare readings, Sir Steuart taking the dignified parts of Prospero, the Duke, etc. Sir Alfred Croft gave little dinners in his snug bachelor cottage. We had sunrise picnics to Senchal, and visits to the tea-gardens.

Lyon was acting as deputy commissioner temporarily. He was doing too much and had been looking white and unwell when he was seized with internal hemorrhage, and died, aged thirty-two. I saw him just before—still able to give me a smile. We put on his tombstone in the Darjeeling Cemetery:

For who can always act? but he

To whom a thousand memories call,

Not being less but more than all

The gentleness he seemed to be,

Best seemed the thing he was, and joined

Each office of the social hour

To noble manners, as the flower

And native growth of noble mind.

I liked my new work of general superintendence over the officers of registration of deeds in Bengal. I was m y own master and could travel where I liked, and look up m y friends. In the hot weather I went to see Whitmore at Soori and Carstairs at Doomka, Bourdillon at Chupra and Tytler at Sewan. I lived for a time in Calcutta with Marsden, the Police Magistrate, and Judge Norris, a radical barrister and an amusing, down right character. How he hated Indian life! He loved to tell us his bar stories of the western circuit. In the rains I arranged for a house-boat and tug, and went a tour with my Police Superintendent through canals and the Sunderbans to Khoolna, paying surprise visits to the Registration Officers on the banks.

(Left.) “Sir Richmond Ritchie, K.C.B., Under-Secretary Of State For India.[14] (Right) Anne Thackeray Ritchie c. 1890.

In November 1888 the sad news of m y dear mother’s death reached me by telegram, and we took three months’ leave home, by Bombay and Marseilles. My wife managed wonderfully without a nurse. Our white-haired baby was a great favorite on board; one day at dinner, we looked up and saw her in the butcher’s arms. For the first time we came through the canal using the electric light. We were met at Marseilles by my two sisters and Edith Sichel.

We went to the Hôtel de la Poste at Avignon. It was bitter cold weather, and we sat together in the comfortable warm salon talking. The Pope’s great buildings were gloomy and forbidding in the mistral. Félicie met us in Paris and we stopped at the St. Romain and had the usual play-going. We saw Judie as Mlle Nitouche, and the Abbé Constantin at the Gymnase. Paris was under snow. Theo looked a little red dot in her scarlet cape with Félicie in the snowy Tuileries. It seemed strange, but appropriate, to see my little daughter there.

Richmond had taken a house in Lexham Gardens and received us most hospitably. All the cousins were gathered in the hall to welcome their little Indian visitor, and made an escort to carry her upstairs, as she was very tired. Her white hair used to get quite black in the murky London fogs, but she was always in a good humor, and prattled away to her visitors. She used to imitate the Calcutta crows. Uncle Ted was established in his new practice at Camberley and we paid him two visits, enjoying a day’s hunting in his company. We had a very short stay in Paris on the way back. The street boys were calling out the last news about Boulanger in front of the little salle à manger at the St. Romain. Faithful Félicie saw us through as usual. We made the long railway journey to Brindisi, stopping the night at the Hôtel Brun at Bologna. Theo was wonderfully good. I carried her on board at Brindisi on a balmy night, with her eyes wide open, and she noticing everything. We travelled on a crowded Australian steamer, the Victoria. We seemed quite lost in the crowd, and had our meals at a little table on a lower deck frequented only by Australians who did not love a crowd. Theo was one year and eight months, and had just learnt to toddle. She delighted in running up and down the deck, her white hair streaming behind her in the wind. We stayed at the Bucklands’ in Calcutta and then went to Berhampore, district Murshidabad, at the beginning of the hot weather.

Our house was in the corner of a big square, built for cantonment purposes in old days; at the back we looked out on the river, the Bhāgirathi, a river which takes off from the Ganges, and which forms the western limit of the Ganges Delta on which Calcutta is situated. The house had a particularly picturesque interior, the drawing-room being enclosed by Moorish arches, with passages all round and a marble floor. Near us were the Gallois,’ a bourgeois family from Lyons engaged in silk manufacture. Eugène and Alphonse were amusing old Frenchmen, while Madame was voluble and very French. They had pretty children, who played with Theo. At the same time as we arrived there had come a strange couple. He was a newly arrived civilian, a handsome if rather sickly-looking young man, entirely educated at home, in Ireland, with his head full of the most advanced ideas, a theosophist, radical, vegetarian and I know not what else. I found him a difficult subordinate to train. His wife was a Russian girl, red-haired, with great blue eyes. There was something very taking about her, but she was wild and uncouth. This original pair were christened the Popoffs.[15] I have a soft corner for them in my heart, as they were very appreciative of Theo.[16]

← Table Of Contents →

SOURCES:

[1] “The ‘Calcutta Gazette.’” The Englishman’s Overland Mail. (London, England) February 27, 1889.

[2] Ritchie, John Gerald. The Ritchies In India: Extracts From The Correspondence Of William Ritchie, 1817-1862. J. Murray. London, England. (1920): 255, 259, 266, 271, 304-305, 307-310, 347.

[3] Ancestry.com. England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1916-2007 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2007. [Original data: General Register Office. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London, England: General Register Office. General Register Office; United Kingdom; Volume: 1a; Page: 232.

[4] Ritchie, John Gerald. The Ritchies In India: Extracts From The Correspondence Of William Ritchie, 1817-1862. J. Murray. London, England. (1920): 314-315; Wilkins, Philip A. The History Of The Victoria Cross.The Naval & Military Press Ltd. East Sussex, England. (2012): 110; “War Office.” The London Gazette. (London, England) April 29, 1862; Low, Ursula. Fifty Years With John Company: From The Letters Of General Sir John Low Of Clatto, Fife. John Nurray. London, England. (1936): 363-366, 393.

[5] Ancestry.com. England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: England, Births and Christenings, 1538-1975. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013. Ancestry.com. India, Select Births and Baptisms, 1786-1947 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: India, Births and Baptisms, 1786-1947. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

[6] W.C. “Some Transactions Of The C.H.S.” Bengal: Past & Present. Vol. II, No. 2 (April, 1908): 191-210.

[7] Cox, Julian; Ford, Colin. Julia Margaret Cameron: The Complete Photographs. Getty Publications. Los Angeles, California. (2003): 520.

[8] Gill, Gillian. Virginia Woolf: And The Women Who Shaped Her World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Boston, Massachusetts. (2019): 372; Ritchie, John Gerald. The Ritchies In India: Extracts From The Correspondence Of William Ritchie, 1817-1862. J. Murray. London, England. (1920): 259.

[9] “I suppose the Patron meant that if you give a man a fish, he is hungry again in an hour. If you teach him to catch a fish you do him a good turn.” Thackeray Ritchie, Anne. Mrs. Dymond. Bernhard Tauchnitz. Leipzig, Germany. (1886): 95.

[10] Austin, Stella. Jack Frost’s Little Prisoners: A Collection of Stories for Children. Skeffington & Son. London, England. (1887): 19-41.

[11] Cox, Julian; Ford, Colin. Julia Margaret Cameron: The Complete Photographs. Getty Publications. Los Angeles, California. (2003): 426; Ritchie, Ritchies In India, 346.

[12] Ritchie, John Gerald. The Ritchies In India: Extracts From The Correspondence Of William Ritchie, 1817-1862. J. Murray. London, England. (1920): 256, 306.

[13] Heine, Heinrich; (tr.) Jarrett, H.S. The Book Of Songs. Constable & Company Ltd. (1913.) At the time when Ritchie was staying with him at Chevremont, Jarrett was translating Abū al-Fazl ibn Mubārak’s Ain I Akbari, one of the first Persian texts to be translated into the English language. [Abū al-Fazl ibn Mubārak (tr.) Jarrett, H.S. Ain I Akbari Vol. II. The Asiatic Society Of Bengal. Calcutta, India. (1891); Cohn, Bernard S. Colonialism And Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. (1996): 61.]

[14] Ritchie, John Gerald. The Ritchies In India: Extracts From The Correspondence Of William Ritchie, 1817-1862. J. Murray. London, England. (1920): 264.

[15] This is a reference to Commander Popoff of the First Bulgarian Infantry who was in the headlines at the time for his highly publicized arrest, trial, and subsequent pardon on charges of embezzlement. “The Arrest of Popoff.” The Edinburgh Evening News. (Edinburgh, Scotland.) March 15, 1888; “Major Popoff Pardoned.” The Glasgow Evening Post. (Glasgow, Scotland.) June 29, 1888.

[16] Ritchie, John Gerald. The Ritchies In India: Extracts From The Correspondence Of William Ritchie, 1817-1862. J. Murray. London, England. (1920): 357-371.