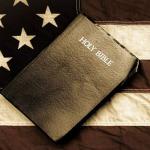

Despite the dividing line often being blurred, Christendom and Christianity are not the same thing. Christendom is far bigger and broader than Christianity, encompassing non-Christian beliefs like the deism of Thomas Jefferson, the Unitarianism of many high-level politicians in American history, or the beliefs of outliers like the Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses. Under Christendom, America created a new national religion that took concepts and images from Old Testament Israel and reappropriated them. In A Call to Resurgence, I say it this way:

Think of American civil religion in biblical terms: America is Israel. The Revolution is our Exodus. The Declaration of Independence, Bill of Rights, and Constitution compose our canon of sacred scripture. Abraham Lincoln is our Moses. Independence Day is our Easter. Our national enemies are our Satan. Benedict Arnold is our Judas. The Founding Fathers are our apostles. Taxes are our tithes. Patriotic songs are our hymnal. The Pledge of Allegiance is our sinner’s prayer. And the president is our preacher, which is why throughout the history of the office our leaders have referred to “God” without any definition or clarification, allowing people to privately import their own understanding of a higher power.

In this blatant borrowing, the spiritual symbols were kept and the substance was lost. But it is no wonder people mistake Christendom for Christianity. Christendom wanted the social benefits of Christianity without the Scriptural beliefs. President George Washington said in his farewell address, “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, Religion and Morality are indispensable supports…. Reason and experience both forbid us to expect that National morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”(1) A century and a half later, President-elect Dwight Eisenhower said, “Our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply-felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.”(2)

The Death of Christendom

When people care little about the content of faith, it is no surprise when that faith becomes irrelevant to real life. Christendom as an all-powerful system has quickly begun to wind down over the course of just a few decades. Nations that were part of Christendom are now largely post-Christendom. The Bible is no longer a highly regarded book, a pastor no longer a highly regarded person, and the church no longer a highly regarded place. Major portions of our society have wildly different responses to this new order.

THE REACTIONARY RIGHT

People on the political right who claim to be Christian are gravely concerned about the direction culture is trending. Conservative Christians talk a lot about “taking back America,” with older voices appealing for a return to traditional values they claim led to a more sane and safe world. Their confusion of Christendom and Christianity means they interpret the decline of Christendom as a decline in Christianity, which may not in fact be the case. For many people, the reign of Christendom simply meant that on special occasions you were to show up at some sacred building to get blessed by some religious leader so you could live some sort of good life as more of a fake convenience than a faith commitment.

In Christendom, social benefits came with professing a faith you infrequently practiced and unlikely possessed, and the system produced cultural Christians like me. I was born Catholic, baptized as baby, believed in some vague concept of God, showed up for worship on Christmas and Easter, endeavored to live a decent life, called myself a Christian because I was born into it just like I was born Irish, but I was not born again through faith in Jesus.

Now that Christendom is dead, younger generations are less likely to fake faith. That phenomenon explains the quantifiable rise in the numbers of dechurched, the unchurched, the “nones” with no religious affiliation as well as the “spiritual but not religious” who have little interest in “organized religion.” It also illuminates why a lot of devout grandparents not only worry about the direction of culture but their dating, relating, and fornicating grandkids who will never show up in church until their funeral.

Among the reactionary rights favorite Bible verses is 2 Chronicles 7:14, where God says, “If my people who are called by my name humble themselves, and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven and will forgive their sin and heal their land.” Religious leaders of this team frequently appeal to this verse, particularly at prayer meetings. The problem? This is not an ironclad promise to any modern nation. God spoke those words not to America but to ancient Israel, and the “land” in question is not the White House but the Promised Land.