One of the basic principles of the Catholic approach to Scripture is that, in the words of Augustine, the New Covenant is revealed in the Old and the Old Covenant is only fully revealed in the New. This is a view of the Jewish Bible that goes right back, not to Augustine nor the Fathers, but to the New Testament itself and even to the lips of Jesus, who, meeting the disciples on the Emmaus Road, tells them, “O foolish men, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken!” and the “beginning with Moses and all the prophets, …interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself.” He flatly tells the disciples:

“Thus it is written, that the Christ should suffer and on the third day rise from the dead, and that repentance and forgiveness of sins should be preached in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem.” (Luke 24:26-47)

In short, if you want to really get what the Old Testament is talking about, says the Risen Christ, the first thing you have to understand is that it is about him. (For more information on this way of reading scripture, see a) CCC paragraphs 115-119 and my book Making Senses Out of Scripture: Reading the Bible as the First Christians Did. So Jesus constantly speaks of himself as the “fulfilment” of Scripture and Paul, speaking of events in Torah, tells us, “Now these things happened to them as a warning, but they were written down for our instruction, upon whom the end of the ages has come.” (1 Cor 10:11). All through the New Testament, Jesus and the apostles will read the Old Testament with this sense of a secondary meaning behind it, all pointing to him. The manna, says Jesus, is an image of himself: the Bread of Life. Likewise, Jacob’s stairway to heaven. Likewise, the Bronze Serpent in the wilderness is an image of Christ crucified, the torn curtain in the Temple is the body of Christ, torn for our salvation to open the way into the Holy of Holies. The passage through the Red Sea is an image of baptism. The Passover Lamb is an image of Christ’s sacrificial death. Noah’s Ark an image of the Church. Jerusalem an image of heaven. And on and on.

This, by the way, gives the lie to the notion that the early Christians were basically just pagans borrowing from Gentile pagan fertility cults and cooking up a new dying and rising god like Osiris. As C.S. Lewis notes, the curious thing about the New Testament is how deeply Jewish it is and how little interest in (and even contempt for) paganism it has:

The very thing which the Nature-religions are all about seems to have really happened once: but it happened in a circle where no trace of nature-religion was present. It is as if you met the sea-serpent and found that it disbelieved in sea-serpents: as if history recorded a man who had done all the things attributed to Sir Launcelot but who had himself never apparently heard of chivalry. . . . Now if there is such a God and if He descends to rise again, then we can understand why Christ is at once so like the Corn-King and so silent about him. He is like the Corn-King because the Corn-King is a portrait of Him. The similarity is not in the least unreal or accidental. For the Corn-King is derived (through human imagination) from the facts of nature, and the facts of nature from her Creator; the Death and Re-birth pattern is in her because it was first in Him. On the other hand, elements of nature-religion are strikingly absent from the teaching of Jesus and from the Judaic preparation which led up to it precisely because in them Nature’s Original is manifesting itself. . . . Where the real God is present the shadows of that God do not appear; that which the shadows resembled does. (Miracles)

What anybody reading the New Testament attentively quickly notices is that the whole Dan Brown, “Christ as Osiris/World’s Sixteen Crucified Saviors”, “This is Warmed-Over Paganism” reading of the New Testament has nothing to stand on. Pagan poets are cited a couple of times by Paul, as a sort of concession to the cultural sensibilities of his audience of Gentiles who care about that sort of thing, but then Paul’s mind instantly reverts back to his rabbinic training and he is again revolving the mysteries of the Old Testament–what he calls the “oracles of God” (Romans 3:2). The other apostles do the same, as does Jesus. The rest of the time paganism is either totally ignored or treated dismissively as a thing for darkened minds and the folly of the Gentiles (cf. Ephesians 4:17-19). The New Testament is multicultural in one sense only: it sees the gospel as addressed to all people. But it is emphatically monocultural in that it sees the gospel as deriving from one people only. In the words of Jesus himself, speaking to a woman who hails from a people who are kissing cousins of Israel: “Salvation is from the Jews” (John 4:22). The whole notion of Jesus as an imitation pagan god is 19th century rubbish that is plausible only to people who have not really paid attention to the New Testament’s overwhelmingly Jewish mental universe. Almost every syllable of it is written by people whose minds are completely marinated in and formed by Jewish scripture and who see Jesus, not as the fulfilment of the Sybilline Oracle, the Egyptian Book of the Dead, or the Vedas, but of the law and prophets of Israel. Later Christian reflection will poke around in certain Gentile poets (Vergil, for instance) and say, “Hey, looks like even the blind and foolish Gentiles may have caught a glimpse of the truth.” But that is a project which the apostles evince essentially no interest in. The closest they come is Paul on the Areopagus remarking that the monument “To an Unknown God” affords him a chance to tell the Athenians that God’s Name, and then launching into the announcement of Jesus and the Resurrection. But even that exchange shows the remoteness of Paul’s mental universe from his hearers. They take him to be referring to a new god and his consort goddess(“Anastasis”=resurrection) and Paul’s letters to the Corinthians will likewise make clear that Paul’s Jewish mental world is often at sixes and seven with his Gentile converts. Yet he will never appeal to their poets and legends and myths in order to teach his gospel. Instead, he appeals to a) the traditions about Jeeus that come from the apostles and eyewitness, most of whom are still alive when he writes; b) his own credentials as an eyewitness; and c) Jewish scripture, which Jesus fulfils according to Paul.

One of the things this way of reading Scripture profoundly affects–indeed the main thing–is how the readings at Mass are arranged. Typically, the Old Testament reading and the Gospel are arranged in such a way that the Gospel is a commentary on the “hidden meaning” of the Old Testament “oracles”. This is what Revelation is getting at, by the way, in its own peculiar way. Revelation is structure like the Mass. It begins “I was in the Spirit on the Lord’s Day.” In other words, “I was at Mass. It was Sunday.” It opens with letters to seven Church urging various kinds of repentance and reform. In other words, a penitential rite. It then moves on to a sort of heavenly liturgy (all of the furniture of which is borrowed from Jewish liturgical practice), in which we have both the opening of scrolls (the liturgy of the words) and finally the great “marriage supper of the Lamb” (the liturgy of the Eucharist).

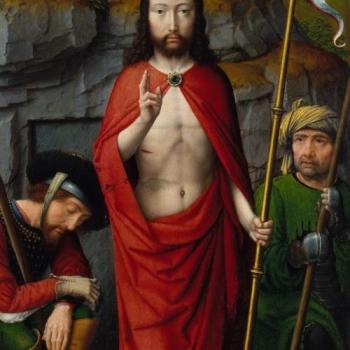

During the liturgy of the word, Revelation shows us this image:

And I saw in the right hand of him who was seated on the throne a scroll written within and on the back, sealed with seven seals; 2 and I saw a strong angel proclaiming with a loud voice, “Who is worthy to open the scroll and break its seals?” 3 And no one in heaven or on earth or under the earth was able to open the scroll or to look into it, 4 and I wept much that no one was found worthy to open the scroll or to look into it. 5* Then one of the elders said to me, “Weep not; lo, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that he can open the scroll and its seven seals.” 6* And between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders, I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain, with seven horns and with seven eyes, which are the seven spirits of God sent out into all the earth; 7 and he went and took the scroll from the right hand of him who was seated on the throne. 8* And when he had taken the scroll, the four living creatures and the twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb, each holding a harp, and with golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints; 9* and they sang a new song, saying, “Worthy art thou to take the scroll and to open its seals, for thou wast slain and by thy blood didst ransom men for God from every tribe and tongue and people and nation, 10* and hast made them a kingdom and priests to our God, and they shall reign on earth.” (Revelation 5:1-10)

In other words, the Old Testament oracles cannot be grasped apart from the revelation of Christ. It’s the same thing Luke is getting at when he says the Risen Christ “open their minds to understand the Scripture” and Paul is getting at when he says of his unbelieving Jewish brothers, “But their minds were hardened; for to this day, when they read the old covenant, that same veil remains unlifted, because only through Christ is it taken away. Yes, to this day whenever Moses is read a veil lies over their minds; 16 but when a man turns to the Lord the veil is removed” (2 Cor 3:14-16).

Bottom line: The apostolic faith is that we cannot really understand the Old Testament at its heart apart from the gospel. So the Mass tends to pair up the Old Testament Reading with the Gospel reading in such a way that the former informs the latter and the latter illuminates the mystery hidden in the former.

So, for instance, yesterday’s reading do this in surprising and subtle ways. In Genesis we read:

The Lord God took Abram outside and said, “Look up at the sky and count the stars, if you can. Just so,” he added, “shall your descendants be.” Abram put his faith in the LORD, who credited it to him as an act of righteousness.

He then said to him, “I am the LORD who brought you from Ur of the Chaldeans to give you this land as a possession.” “O Lord GOD,” he asked, “how am I to know that I shall possess it?” He answered him, “Bring me a three-year-old heifer, a three-year-old she-goat, a three-year-old ram, a turtledove, and a young pigeon.” Abram brought him all these, split them in two, and placed each half opposite the other; but the birds he did not cut up. Birds of prey swooped down on the carcasses, but Abram stayed with them. As the sun was about to set, a trance fell upon Abram, and a deep, terrifying darkness enveloped him.

When the sun had set and it was dark, there appeared a smoking fire pot and a flaming torch, which passed between those pieces. It was on that occasion that the LORD made a covenant with Abram, saying: “To your descendants I give this land, from the Wadi of Egypt to the Great River, the Euphrates.”

While the gospel recounts the Transfiguration:

Jesus took Peter, John, and James and went up the mountain to pray. While he was praying his face changed in appearance and his clothing became dazzling white. And behold, two men were conversing with him, Moses and Elijah, who appeared in glory and spoke of his exodus that he was going to accomplish in Jerusalem. Peter and his companions had been overcome by sleep, but becoming fully awake, they saw his glory and the two men standing with him. As they were about to part from him, Peter said to Jesus, “Master, it is good that we are here; let us make three tents, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” But he did not know what he was saying. While he was still speaking, a cloud came and cast a shadow over them, and they became frightened when they entered the cloud. Then from the cloud came a voice that said, “This is my chosen Son; listen to him.” After the voice had spoken, Jesus was found alone. They fell silent and did not at that time tell anyone what they had seen.

At first blush, it may be hard to see the connection, but then you notice something. That passage in Genesis about going out and counting the stars? We’re used to thinking of it from the illustrations in our Golden Books of Bible Stories or Hallmark cards. There’s Abraham out there under a spectacular night sky in the desert, staring up at the Milky Way with the words of this spectacular promise ringing in his ears.

Only here’s the thing: Shortly after God tells him, “Look up at the sky and count the stars, if you can” we read, “As the sun was about to set…”. The author of Genesis is one subtle cat. The implication of the text is that when Abraham looked up at the sky, it was broad daylight. He could not count the stars at all–but he knew they were there all the same. He had faith in what he knew to be true, but could not see.

The Transfiguration is about exactly the same thing. In it, the apostles are allowed to see in a glimpse what Jesus always is. Just as the stars are always there even when veiled by the blue sky, so Jesus is actually always the glorious Son of God even when his pedestrian, sweaty, grimy, humanity veils it. It is, by the way, the same lesson that Eucharistic miracles teach. Now and then, God will grant that a host turn to flesh or bleed, as at Lanciano and Betania. When such things happen, they are not “real” miracle as distinct from boring non0-miraculous Eucharists like the one you had at your sleepy parish yesterday morning. They are reminders of what is always true at every Eucharist. The glory is against typically veiled, as the sky veils the stars and the humanity of Jesus veiled his deity. But behind the veil, the glorious Reality continues to burn as bright as ever and the day is coming when we will all see it.