I was struck by the readings on Sunday, regarding the covenant with Abraham and the Transfiguration. One key to understanding Scripture is to look at how the Church combines them in the Mass readings. The gospel reading is nearly always a commentary (sometimes very subtle) on the Old Testament text in the first reading. Both the readings on Sunday were, by no accident, “vision literature’ and both relate stories that describe real-world experiences of Otherworld things pertaining to the future, to the idea of the promises of God.

The vision experience of Abraham in Genesis 15 is well known and it culminates with a childless man being told that his descendants will be like the stars of the sky and will be given the land from the Wadi of Egypt to the Euphrates. A careful reading of the text is revealing, because God conducts Abraham outside to “Look toward heaven, and number the stars, if you are able to number them.” (Ge 15:5) in the daytime. It is not until a little later that the sun goes down (v. 12). So the point of the promise is that God makes it when there is zero evidence that Abraham is going to have any descendants at all, much less as many as the stars.

The promise of the land is likewise interesting because of the way the idea of “home” will unfold in biblical revelation. There is something platonic in it, much as there has always been a quest for the idealized Home in the American experience. The Puritans who came to America seeking to found a City on a Hill were in earnest and they got their ideas straight and undiluted from the Old Testament prophetic tradition which longed for the day when

It shall come to pass in the latter days

that the mountain of the house of the LORD

shall be established as the highest of the mountains,

and shall be raised above the hills;

and all the nations shall flow to it,

and many peoples shall come, and say:

“Come, let us go up to the mountain of the LORD,

to the house of the God of Jacob;

that he may teach us his ways

and that we may walk in his paths.”

For out of Zion shall go forth the law,

and the word of the LORD from Jerusalem.

He shall judge between the nations,

and shall decide for many peoples;

and they shall beat their swords into plowshares,

and their spears into pruning hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war any more. (Is 2:2–4)

We who live after the genocide of Natives, slavery, lynching, Jim Crow and the rest of the dark history of white Christians in North America snort with cynicism at the idealism of the Pilgrims and similar Utopians in search of Home, but the fact remains that this prophetic streak of intense desire for Home runs right through Israelite (and American) history and that those who sought it often did so in utter sincerity. Not everybody is a hypocrite. Human history is chock full of it. That’s what Hebrews is getting at when it tells us:

These all died in faith, not having received what was promised, but having seen it and greeted it from afar, and having acknowledged that they were strangers and exiles on the earth. For people who speak thus make it clear that they are seeking a homeland. If they had been thinking of that land from which they had gone out, they would have had opportunity to return. But as it is, they desire a better country, that is, a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared for them a city. (Heb 11:13–16).

The clash between this search for Home and the gritty realities of fallen human experience is what both the Old Testament and Christian history is all about. The Promised Land had turned out not to be enough. The alabaster cities did not gleam undimmed by human tears. They brought their transcendent hope with them, to be sure. But they had also brought themselves, resulting in the whole painful drama of apostasy, exile, and conquest.

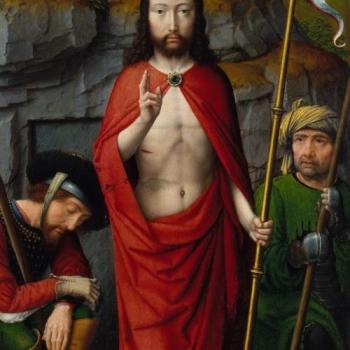

So in the story of the Transfiguration, the apostles (standing squarely in the middle of Abraham’s Promised Land That Was Not Enough) are vouchsafed a ‘Mountaintop Experience” in that they are permitted a glimpse of the heavenly Home of which the Promised Land was ever only an image. They get a foretaste of Jesus as he really is–a foretaste of “our commonwealth … in heaven, and [the] Savior… who will change our lowly body to be like his glorious body, by the power which enables him even to subject all things to himself.” (Php 3:20–21).

Interestingly, Peter draws exactly the wrong conclusion from this and attempts the classic human mistake of making such an experience into Home. He wants to build tabernacles and stay. “O moment stay!” says Goethe’s Faust. It is one of the most insidious forms of idolatry: the desire to make peak experiences eternal. It results in living in the past. We see it in everything from Sunset Boulevard to the cry “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN” to the attempt to preserve 1956 Cleveland American Catholicism in Fortress Catholic groups huddled around the Traditional Latin Mass. And so God simply ignores Peter’s silly idea, saying ‘This is my Son, the Chosen One. Listen to him’. He then underscores the point by the disappearance of Moses and Elijah, leaving only Jesus. Moses and Elijah (and the entire Promised Land) were only signs pointing to the Reality, who is Christ. The vision was granted so that the cross could be faced, not avoided forever.

It may be odd to hear of a Tradition (the nature of which would seem to be all about living in the past) condemning living in the past as a diseased thing. But the reality is that the biblical tradition is, paradoxically, creative and forward-looking. “Here we have no continuing city” says Hebrews 13:14. Every attempt to build one is doomed. The biblical prophetic tradition looks to the past for one reason: not to maintain a museum, but to find roots to nourish a growing plant. The growth is all and the roots exist only for the sake of the growth. Any traditionalism that becomes a mere root fetish, much less a cancer attacking the growing plant, is simply a form of heresy.