Let’s jump right into the origin story. Luke tells the story of Jesus birth. Jesus’ mother, while Jesus was still in the womb, said the following words while filled with the Spirit:

[God] has demonstrated power with [God’s]

Luke 1:51-52

arm; [God] has scattered those whose pride

wells up from the sheer arrogance of their

hearts. [God] has brought down the mighty

from their thrones, and has lifted up those of

lowly position; [God] has filled the hungry

with good things, and has sent the rich away

empty.

Jesus grows up. He starts his ministry and is tempted by the devil in the wilderness. The temptation of Jesus by the devil reveals the manner in which Jesus understands his authority. Jesus’ sense of authority bears little to no similarity to kingly authority. In the wilderness, he is tempted politically, economically, and religiously to assert his messiah-ship. But he refuses. The diabolical nature of his temptation isn’t due to the source of the temptation—that the offer of political, economic, and religious power comes from the devil instead of God. Rather, the temptation concerns the sort of reign Jesus should pursue. Jesus is the unking.

Later in Luke 4, right after his trial and baptism, Jesus goes to his home town (Nazareth) and gives a political manifesto of liberation for the poor and oppressed, essentially announcing his messiah ship and the coming of Jubilee (the “year of the Lord’s favor”). Provocatively, Jesus seems willing to include oppressors in the kingdom. Which is why his hometown folks—who most likely knew him well—try to kill him.

Just to jump ahead a bit, in Luke 17:21 Jesus says (in words that would later inspire the development of Leo Tolstoy’s anarchism): “The kingdom of God is within you” (or among you). In the context, it seems to be a way of suggesting that the kingdom of God isn’t a place, a demonstrative regime change, or a clear event. Rather it is here. Now.

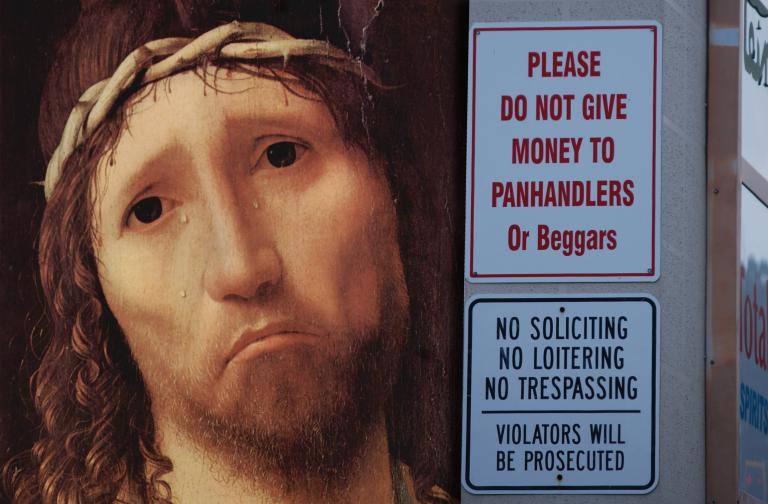

Later, when Jesus heard his friends arguing amongst themselves the pecking-order in this kingdom (Luke 22:25-26) he tells them: “The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them, and those who exercise authority over them call themselves Benefactors. But you are not to be like that. Instead, the greatest among you should be like the youngest, and the one who rules like the one who serves.”

Jesus is asking his friends to rethink everything they know about socio-political realities. The next time you read the Gospel of Luke, try to read it through the lens of Jubilee—where the ones who have accumulated have to give up and the ones who have lost receive. Jesus tells the rich young ruler to sell everything and give it to the poor. He says the same thing to his disciples, by the way.

In case you think only Luke is quotable for radicals, the Gospel of John is also juicy. For example, Jesus calls Satan the “prince of the world” which is likely a way of referring to the Roman Empire.

In John 18:36, in a conversation with Pilate, we learn that Jesus’ kingdom is not of this world. Actually, it is perhaps better translated as “not from this world.” Usually, this is interpreted as saying that Jesus’ kingdom is spiritual or heavenly. However, the way such dualistic language worked in that time makes such a meaning unlikely. Rather, Jesus is saying his kingdom is different. It is something entirely new. It is a gift from God–it comes from God.

After the resurrection, we read of an account of civil disobedience in Acts 5. When the disciples were ordered by authorities to stop their teaching, they answer: “We must obey God rather than any human authority.” Here’s what most people hear when they read that: “We must obey God rather than any human authority in those rare circumstances where there is a clear and obvious contradiction between what the law says and God says, since God’s laws trump human laws.” I’m not so sure. If you believed that your messiah was a socio-political/religious unking who died and then rose from the dead (and then mystically poured his Spirit out upon you), then you might simply mean “we must obey God, not any human authority.”

This helps us understand the way in which the early church practiced community. They were encouraged, among other things, to work out their issues internally rather than appealing to the courts. In Romans 12, Paul argues that his friends in Rome should “not be conformed to this present world [read: empire], but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, so that you may test and approve what is the will of God.” This is, again, often read as a call to be spiritual or heavenly minded. But, given the larger context, it is perhaps better to see it as a challenge to stop being so Roman-ish and, instead, pursue the way of love.

I am often asked to justify my anti-imperial reading of the New Testament. After all, the word “empire” doesn’t appear in the New Testament. Well. Here’s the thing. The early church was sneaky. They didn’t want to sound overtly treasonous. So usually we have to try to inhabit their context with our imaginations to see Rome closer to they way they saw it. And no writing is as anti imperial as, perhaps, John’s Revelation. Read Revelation 13, 14, and 17 for a not-so subtle picture of oppressive Rome.