Daniel P. Horan, O.F.M., The Franciscan Heart of Thomas Merton: A New Look at the Spiritual Inspiration of His Life, Thought, and Writing (Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press, 2014).

Daniel P. Horan, O.F.M., The Franciscan Heart of Thomas Merton: A New Look at the Spiritual Inspiration of His Life, Thought, and Writing (Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press, 2014).

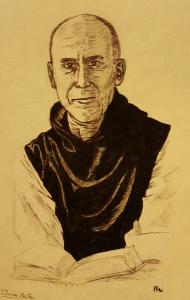

The Seven Storey Mountain, Thomas Merton’s spiritual autobiography, has touched the hearts and souls of countless readers. It’s worth noting here that the book was released on October 4, 1948, the Feast of St. Francis of Assisi. Whether this was intentional or not, no one knows. But if anyone could have appreciated this coincidence, it would have been Merton himself, who nurtured a lifelong connection with both the Franciscan community and its charism.

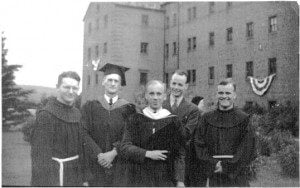

Daniel Horan, a Franciscan priest finishing his theology doctorate at Boston College, focuses here on Merton’s Franciscan influences. Readers of The Seven Storey Mountain know that Merton seriously considered joining the order in 1940, but scruples about his past prevented him. Still, he did teach English at St. Bonaventure University in western New York, a Franciscan school founded in 1858, for a year and a half before he entered the Trappists in December 1941. Father Horan ably and convincingly argues that Merton’s encounter with the Franciscans was no mere interlude, but an event of major importance that shaped the monk’s spirituality and writing.

Through the years, Horan writes, Merton’s heart remained “undoubtedly Franciscan.” His devotion to the person of St. Francis of Assisi, as well as to the order itself, “stayed with him long after his hopes of becoming a friar were dashed.” At St. Bonaventure’s, he joined the Franciscan Third Order, a group of laypeople dedicated to living out the Franciscan charism in their daily lives. Furthermore, the friars helped him grow in self-awareness of his monastic vocation.

Equally important, Merton received what Horan calls the “best possible education in the Franciscan intellectual tradition of his time.” Through the influence of Father Theophilus Boehner at the university’s Franciscan Institute, he was exposed to the writing of Franciscan medieval philosophers, particularly St. Bonaventure (1221-1274) and Blessed John Duns Scotus (1266-1308). Although Thomstic Scholasticism was the prevailing school of Catholic philosophy in Merton’s day, the Franciscan intellectual tradition had a greater appeal to him, with its “primacy of love.”

In his first two chapters, Father Horan looks at the lives, respectively, of St. Francis and Thomas Merton. With his characteristically refreshing approach and engaging style, he compares their commonalities, including:

- A recognition of God’s activity in the world

- An openness to women and men of other faiths

- A concern for social justice

- An emphasis on non-violence and peacemaking

- A common view of God, the Incarnation, and human personhood

A major themes in Merton is his emphasis on “the true self” and the “false self,” which he expounds most fully in New Seeds of Contemplation (1962). Our “true self,” Merton contends, consists in becoming more fully the person God intended us to be, while the “false self” draws us away from that end. While this notion was not unique to Merton, Horan argues that he did make it more meaningful and relevant to modern spiritual seekers.

Horan also shows how Duns Scotus, for whose work Merton had a strong affection, influenced Merton’s writings. For Scotus (and for Merton), it’s not what we do or have, nor our actions, that makes us loved by God—it’s who we are, our own individual and uniquely formed selves. As Merton would write in New Seeds, “the perfection of each created thing is not merely its conformity to an abstract type but in its own individual identity within itself.” More famously, Merton writes:

For me to be a saint means to be myself. Therefore the problem of sanctity and salvation is in fact the problem of finding out who I am and of discovering my true self.

For Merton, the universal call to holiness is connected to each of us discovering that true self. Horan adds: “our discovery of God in discovering ourselves should change us.”

Merton, Horan writes, became the “prophetic voice that he called others to adopt.” But he didn’t become a prophet overnight. It was a vocation that he grew into over time, through his prayer life and his writing. Merton’s life, Horan writes, was “a life of conversion.” Many of the issues he addressed are ones we still face today, including ecology and the environment, interreligious dialogue, and peacemaking.

During the 1960’s, Merton took a strong interest in “man’s true place as a dependent member of the biotic community.” For both Merton and St. Francis, ecology was connected to a sacramental understanding of the world, “creation as a sign of the Creator.” Like Francis, Merton had what Horan calls “a radical adherence to solidarity with the other,” which both saw in evangelical terms. Both had a tremendous openness, leading them to identify with what Horan calls the “dehumanized other.” Both exercised an apostolate of friendship emphasizing people’s commonalities, not their differences. This is one of the reasons why both still matter today.

Like Francis, Merton embraced “the vocation of peacemaking.” Whereas the saint personally met with Muslim leaders in an attempt to end the Crusades, Merton would devote much of his later writings to peace in the modern world, which he saw as having a central place in Christianity. Christ was a peacemaker, and as Horan writes, the Incarnation, “how God acts as a human,” is “the most clear indication of how God intends for all humans to act.”

Toward the end of his life, Merton wrote: “I am still in some secret way a son of St. Francis. There is no saint in the Church I admire more than St. Francis.” Like many others, Merton was drawn to what Horan calls the saint’s “bare authenticity.” And the attraction continues today. The ministry of Pope Francis, Horan writes, is a good example of “how Francis continues to be found in unexpected places.”

With The Franciscan Heart of Thomas Merton, Daniel Horan has made a major contribution to Merton studies and our understanding of the Franciscan charism. Its treatment of an overlooked chapter in Merton’s life leads us to a fuller appreciation and deeper affection for a person who, Horan writes, “continues to surprise you.” It leads one to consider more fully such issues as our vocation to holiness, peacemaking and nurturing God’s creation. Because of this, it is not a book to be missed, and I look forward to more books from Daniel Horan’s able pen.