A Hierarchy Divided

As we mentioned earlier, some mainline Protestant Churches formally divided over the slavery issue. Although the Catholic Church did not formally do so, they did side with the prevailing outlook North or South. This was done less out of principle than from fear of inciting local anti-Catholic sentiment by going against the tide of popular opinion.

So what happened was this: when war broke out, Northern bishops supported the Union wholeheartedly, but Emancipation less so. Southern prelates implicitly endorsed if not formally advocated for both slavery and secession. The days when the American hierarchy spoke with one voice through a national bishops’ conference was well over half a century away. The episcopacy was a house divided against itself.

Confederate and Union Bishops

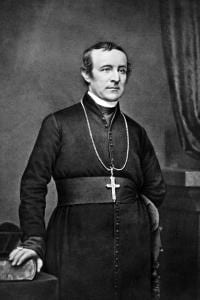

In Cincinnati, Archbishop John Baptist Purcell was the first episcopal voice to formally endorse Emancipation. Meanwhile in Georgia, Bishop Augustin Verot defended slavery and the Confederacy in writing and from the pulpit. (He basically called for a kinder, gentler servitude.) In New York, on the other hand, Archbishop John Hughes, who was said to be notoriously racist, did little to stop the 1863 New York Draft Riots, where eleven Black men were hanged over five days.

Bishops as Political Lobbyists

Some bishops even lobbied abroad. Although Hughes personally had little use for abolition, he did travel to Europe in 1861 and 1862 on behalf of President Abraham Lincoln. He aimed to persuade France and the Holy See not to formally recognize the Confederacy. While neither did so, Vatican authorities did not appreciate his political jockeying, and Hughes’s efforts may well have cost him a Cardinal’s hat.

In 1864, Bishop Patrick N. Lynch traveled to Rome as Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s emissary to the Papal States. As ordinary of the Charleston diocese, Lynch was the legal owner of some 95 slaves who were technically “diocesan property.” In Rome, Lynch advocated for papal recognition of the South, albeit unsuccessfully. Like Verot, he also published a pamphlet defending slavery.

The Limits of Neutrality

Finally there was Martin John Spalding, a native Southerner and Bishop of Louisville. While aiming for public neutrality, he published an anonymous article on the war for L’Osservatore Romano, the unofficial Vatican newspaper. While recognizing the evils of slavery, his sympathies were with the South, and he denounced the pro-Union Archbishop Purcell. Interestingly, after the war, Spalding was named Archbishop of Baltimore, which made him the ranking American prelate.

All of this is as confusing for historians as it is for readers! During the Civil War, bishops acted on their own personal prejudices, engaged in political opportunism, and sought to further their own ecclesiastical careers. For most of them, the cause of human liberty was the last thing on their mind. The story of the American hierarchy during this era is not a proud one.

Epilogue: Too Little, Too Late

In 1866, a year after the war ended, the American bishops, gathered as a body at the Second Plenary Council of Baltimore, calling for outreach to the newly freed slaves. But it was too little too late. The damage had been done, and the healing was far from underway. This was the beginning of Reconstruction, followed by the Jim Crow era. If anything, things were going to get worse for Southern Blacks. And the statements of the bishops were little more than mere words.

Tomorrow we’ll talk about African Americans and the priesthood.

(Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons.)