“The Dignity of the Priesthood”

In a sermon on “The True Priesthood,” delivered at Brooklyn’s St. Ambrose Church in May 1886, Father Daniel Sheehy declared to his parishioners:

What a dignity, the priesthood! Its duties are great. They are commissioned to lead the people to victory. Yours, too, is a duty. They are commanded to teach. You are commanded to learn. They in their own sphere are bid to command; you to obey.

Priests were the officers in God’s army, and their very person was considered sacred. They had an immense dignity, but that dignity didn’t extend to African American men, who weren’t allowed in the priesthood.

“Passing for White”: The Healy Brothers

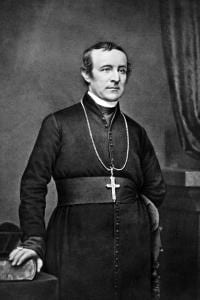

Not unless they “passed for white,” like the three Healy brothers, children of a Black slave and her white owner. When in 1854 James was the first priest of African descent ordained in America, this wasn’t made public. The same was true for Patrick in the Jesuits, and Alexander, a Boston priest. Why? Because of two factors: Catholic prejudice and fear of an anti-Catholic backlash.

In 1874, Patrick was named president of Georgetown, and James became a bishop in Maine the following year. When Rome’s prestigious North American College opened in 1859, Alexander was considered for rector, but at least one bishop objected:

He has African blood and it shows distinctly in his exterior. This, in a large number of American youths, might lessen the respect they ought to feel for the first superior in a house.

Not until the 1950’s was all this made public. A Georgetown student then defaced Patrick’s portrait. At the time the university excluded African Americans. Although it now celebrates Healy as America’s first Black university president, Georgetown overlooks the great pains previously taken to hide that from the public.

The Ordeal of Father Tolton

Augustus Tolton was born a slave in Missouri. His racial identity was no secret, and no American seminary would take him. Ordained in Rome in 1886, the American bishops considered sending him to Africa. Instead he went to Quincy, Illinois. Later he became pastor of Chicago’s first African American parish, St. Monica’s, on the South Side.

“Good Father Gus,” as he was known (perhaps patronizingly), had it tough. Many Catholics refused to accept him as a “real” priest, including his clerical colleagues. Frequent racist abuse and constant stress hastened his early death at 43. Today Father Tolton’s canonization cause is well underway; in June 2019, Pope Francis declared him “Venerable.” He was a martyr to the cause of Black freedom at a time when the altar was segregated.

Desegregating the Altar

Many Northern white Catholics considered Black priests a novelty if not an oddity. In the South, however, the notion of Black priests being raised to the same level as white ones was seen as a threat to the Jim Crow system that dominated the post-Civil War South for a century.

In spite of this, in 1871 the Josephite Fathers and Brothers were formed to serve African Americans. In his book Desegregating the Altar, one of the best ever written on American Catholic history, Stephen Ochs notes that they faced a tough battle advocating for African American priests. Opposition from both Catholics and non-Catholics was fierce.

In Georgia, the notoriously racist Tom Watson, a future U.S. Senator, attacked the Josephites for ordaining Black priests. In June 1914, his Watson’s Jeffersonian Weekly addressed what Watson called “The Sinister Portent of Negro Priests”:

Now when these black men are taught by white priests that they are your equals, and that in being received into the priesthood, they are better than you, what are to be the ultimate consequences? I do not address this vital question to non-Catholics only; I most earnestly implore the Catholics themselves to consider it.

Many Southern Catholic bishops agreed. New Orleans Archbishop James Blenk banned Black priests. In Georgia, Bishop Benjamin Kiely, a Civil War veteran, was buried with a Confederate flag. Several openly employed racist terminology. In his memoir, Church historian John Tracy Ellis recalled that Cardinal John Glennon of St. Louis was well known for “his dislike of Blacks.”

Epilogue

At the start of the twentieth century, Father John Slattery, head of the Josephites, frequently preached against Catholic racism. Eventually he left the Church in frustration and disgust. Ochs notes that during this same period Vatican authorities, not American bishops, took the lead to actively promote a Black priesthood. They at least didn’t fear Southern racism. In 1920, German Divine Word Fathers started the first African American seminary in Mississippi.

The ordeal of the Black priest, as Ochs has called it, lasted well into the twentieth century. While the Civil Rights Movement did a lot to change that, we can’t ignore this terrible blemish on American Catholic history, when the color of one’s skin was an impediment to ordination. The Josephites did what they could, but again it was a hard struggle inside and outside the Church. Today, at least, their experience reminds us today of the true meaning of the word “Catholic”: “universal.”

(Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons)