Sermon for Transfiguration Sunday, 3/5/2011

Text: Matthew 17:1-13

How many of y’all have ever climbed a mountain? Raise your hand if it was higher than 5000 feet. Raise your hand if it was higher than 10,000 feet. Raise your hand if it was higher than 15,000 feet. The highest mountain I’ve ever been up was Pikes Peak in Colorado which is 14,000 feet, and we cheated because we drove to the top. Well, you wanna know how high the mountain was that Jesus, Peter, James, and John climbed? It was only 1500 feet. It’s called Mount Tabor and it’s in the northern part of Galilee.

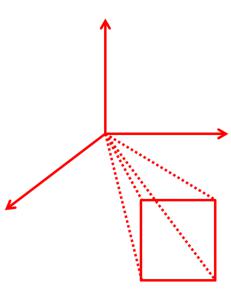

But the strange, beautiful thing called the Transfiguration that happened on top of Mount Tabor is the basis for what Christians call a “mountaintop experience.” Can someone tell me what a “mountaintop experience” is? I would say it’s an intimate exposure to the presence and glory of God. It usually happens on a retreat or a mission trip when we go somewhere and do something with a group of Christians that creates a special bond between us. How many of y’all have had mountaintop experiences? Some of the youth have shared that summer mission trips to Jeremiah Project and Carolina Cross Connection were mountaintop experiences for them. Others say the same thing about our church’s trip to the Dominican Republic.

Last March, I went with other seminary students to visit a Methodist church in the mountains of Guatemala. It was very beautiful, scenic country. But the peak of my mountaintop experience happened during their worship service. When it came time to pray, everyone in the room talked to God at the same time. Has anyone ever experienced a time of prayer like this? They were literally speaking in tongues – some in Spanish, some in native dialects. In that cloud of voices, I felt the presence of the Holy Spirit in a way that I never have before. I wanted to build a hut and stay down there in Guatemala.

But the problem with every “mountaintop experience” is at some point you’ve got to come down. Nobody wants to come down. We’re like Peter saying, “Lord, it is good for us to be here. Why don’t we pitch some tents and live up here on this mountain forever?” Jesus didn’t get mad at Peter, but there were people to heal, sermons to preach, and crowds to feed so they had to get back down to the valley. And so the mountaintop fades into the distance until the next retreat or the next mission trip. But here’s my question: is there a way to bring the mountaintop with us when go back down into the valley?

How do we do it? When we’re in the valley, the mountain feels like a distant dream. But truly, it feels like the mountaintop is the only place where I live for real. In the valley, my life is on autopilot: buying groceries, buckling car seats, checking facebook, washing dishes, and so on. So many things I do are part of a drowsy sleep-walk routine rather than being activities that are meaningful, joyful, or inspiring. And the more that technology invades every aspect of our existence, the more our lives feel like autopilot. So if you never go to the mountaintop, is the valley easier to take? How many of you have seen The Matrix? It’s basically about the nightmare of feeling trapped in the automated existence of modern life. The main character Neo is visited by a guy Morpheus who holds out a blue pill and a red pill. If he takes the blue pill, he can continue to live in blissful ignorance of what’s really going on. But taking the red pill means diving into the reality behind the matrix. In a way, mountaintop experiences with God are like taking the red pill.

So what do we do once we’ve taken the red pill and know that there is a deeper reality to our world than our everyday drudgery? Do we pack our lives into a Volkswagen bus and head to California? Is the answer to live with more spontaneity and imagination? Where can we go where people live that way? Maybe Paris, the city of love, or Brazil, especially this time of year with their Carnaval party going full-blast. I used to live up in Michigan and there was a beat-up anarchist punk house in Detroit where I would visit on the weekends. It was a very creative, exciting place always abuzz with art projects, community gardening, and other activities that felt more real than the routines of my everyday life. I wished I could just drop out of life and become a punk like the rest of them.

The adult in me understands that the longings of my early twenties were mostly escapism. It’s harder to run away from the responsibilities of life now that I have a wife and kids. Yet at the same time, Christian history is filled with people who fled the routines of everyday life to seek God more fully. One example was a man named Anthony who lived in Egypt in the third century. When Anthony read Jesus’ command to the rich young man to sell all his possessions and follow him, he took the advice literally, selling all his stuff and moving out to the desert to spend all of his time praying and devoting himself to God. As time went on, people learned about Anthony’s story, and they ran out to the desert to do the same thing. But as the idea became more popular, something strange happened.

The people who had run off to escape the trivial routines of worldly living actually discovered that the best way to fight off worldly temptations was through establishing a set of daily routines. Without any structure, they got depressed and lost their focus. So they formed monasteries in which they organized a schedule for praying, working in the garden, reading the Bible, and copying scrolls. And somehow despite the fact that they were doing more or less the same thing every day, it wasn’t boring. It was actually more like living on the mountaintop than sleepwalking along through the valley. These first monks and nuns discovered that living authentically is not about ditching routines and replacing them with randomness; it’s about replacing mindless routines with God-centered ones.

Long before Jesus, Peter, John, and James climbed up Mt. Tabor, God knew that we needed mountaintop experiences. That’s why He invented the Sabbath. The problem is that we misunderstand what the Sabbath means. We think that Sabbath is about sacrificing our normal activities to prove to God that we care about Him. The Puritans misunderstood this. They would sit on hard, cold wooden benches for hours and hours listening to their preachers ramble. And they had ushers who would walk the aisles with wooden poles to smack the kids who fell asleep or laughed. But the Sabbath is not about sacrifice; it’s about freedom. It’s about interrupting the valley of autopilot with a mountaintop of sacred time.

We don’t need to find a rocky cliff to sit on for our lives to have mountaintops; we just need to set aside time for God on a regular basis – a week every year, a weekend every few months, a day every week, and an hour every day. When we set aside sacred time for God in which we don’t shop or vacuum or drive our kids to gymnastics, then the sacredness we enjoy during that set-aside time will spill over into the rest of our week so that we find ourselves talking to God while we’re in the middle of washing our dishes and what felt like meaningless routine will become infused with deeper meaning.

Everyone’s needs are different. I do my Sabbath on Mondays, which are my day off. I usually walk around Burke Lake and stop on benches along the way to find a passage in the Bible that speaks to me or read a few pages in whatever devotional book I’m reading at the time. I don’t do this because I think I’m supposed to. I do it because I’ve had a taste of something that I want more of. And the more I taste, the more it feels like I’m still on that mountaintop in Guatemala living richly and fully. Now there are still many days when I don’t give God the time of day even though I’m working for Him full-time; on those days, I’m an utter mess.

But this Lent is an opportunity for those of us who have fallen off the mountain to get back up there. Not only is it a time to give something up for God but to fill the space that we have opened up in our lives with God-time. My challenge to myself and to you for the 40 days that start on Ash Wednesday next week is to start every day with God, whether it’s a prayer you say aloud or a paragraph you write in your journal or a few pages in a devotional book you read or a Bible verse that you find on a website that has a verse for every day. Life’s going to happen to you just like it has before, but don’t be surprised if you find that the same daily routines and experiences feel less like a valley and more like a mountaintop.