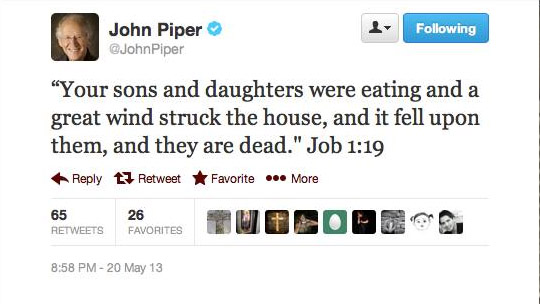

I knew it was coming: the Piper tweet, this time quoting Job in response to the Oklahoma tornado. As the dean of the neo-Calvinist movement, John Piper likes to push the envelope with his commentary on God’s role in natural disasters. He did it about a year ago when tornadoes hit the midwest. In 2007 after the Minneapolis bridge collapsed, he wrote that he and his daughter discussed how God must have done it so the people of Minneapolis would fear Him because our sin against God is “an outrage ten thousand times worse than the collapse of the 35W bridge.” Piper would say that he’s just being Biblical and that it shouldn’t be surprising that speaking Biblically would make people feel uncomfortable. So how do we talk about God’s role in tragedies?

Piper’s perspective on God’s role in disasters has two components: 1) Every event that happens is orchestrated by God for the purposes of His divine plan; 2) Violence within nature reflects God’s infinite anger over human sin, which is primarily understood in Anselmian terms as an abstract offense against His honor. In Piper’s post on the Minneapolis bridge collapse, he cites Luke 13:1-4 where Jesus uses tragedies in His day to issue a warning to his listeners to repent.

At that very time there were some present who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices. He asked them, “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all perish as they did. Or those eighteen who were killed when the tower of Siloam fell on them—do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others living in Jerusalem? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all perish just as they did.”

It’s a pretty strange passage. When Jesus says “perish just as they did,” what is he saying? Is he saying you’ll die too in general or you’ll die in a similarly gruesome way? Piper eisegetes his Anselmian view of sin onto the text by making it about whether humans deserve to die as a punishment from God (“Jesus implies that those who brought him this news thought he would say that those who died, deserved to die, and that those who didn’t die did not deserve to die”). But taking the text at face value, there’s no reason to understand “perishing” as a divinely instituted punishment for sin rather than just a natural consequence of it (e.g. getting tangled up with bad people and dying a violent death as a result). Jesus wasn’t carrying the book of Romans around with him to make sure that his teaching was “Biblical.”

Regardless of what Jesus is saying in that particular passage, there are plenty of examples in the Old Testament of misfortune being proclaimed as the manifestation of God’s wrath and punishment for sin whether it’s a drought or an epidemic or the invasion of an enemy army. The ancient Israelites had no intellectual resources for thinking about disaster as anything other than a personal expression of anger from God. This puts us in an awkward place as Christians living in an age when scientific disciplines like meteorology exists.

Does the authority of scripture force us to say screw meteorology, tornadoes are a warning from God to bring the world into repentance? Or do we say God used to send tornadoes to punish Israel for its sin because the infallible Old Testament prophets say things like that, but now tornadoes happen because of atmospheric thermodynamics? Piper at least recognizes the inconsistency of trying to say that nature only began to behave according to predictable scientific principles after the Bible was written as a clumsy means of rescuing the Bible from being in error. In Piper’s perspective, if Jeremiah and Amos and all the rest were infallible, then the way we interpret disaster should emulate how they interpreted it. Thus he writes about the Minneapolis bridge collapse:

The meaning of the collapse of this bridge is that John Piper is a sinner and should repent or forfeit his life forever. That means I should turn from the silly preoccupations of my life and focus my mind’s attention and my heart’s affection on God and embrace Jesus Christ as my only hope for the forgiveness of my sins and for the hope of eternal life. That is God’s message in the collapse of this bridge. That is his most merciful message: there is still time to turn from sin and unbelief and destruction for those of us who live. If we could see the eternal calamity from which he is offering escape we would hear this as the most precious message in the world.

I imagine that this view is repugnant to most people. Is it because we have gone apostate and are no longer appropriately terrified by God? That’s what folks like John Piper would say. But there’s a subtlety to John Piper’s ideological stance here. God is not a terrifying mystery to Piper, because he knows the exact “meaning” of the collapse of the Minneapolis bridge. John Piper’s God may be a horrible Godzilla, but the prophetic authority Piper gives to himself means that he is sitting on Godzilla’s back holding the reins.

What’s far more terrifying than an angry, dangerous God with predictable motives who offers a canned salvation formula by which people can get right with Him is an unpredictable universe whose violence we do not try to explain even though we stubbornly cling to the belief that somehow a loving Creator is in charge of it. It is God’s unpredictability that makes Him truly sovereign.

The ancient Israelites grasped for prophetic explanations to natural disasters as a means of coping with the terror of an unpredictable universe. If Babylon sacked the city of Jerusalem just because they were the most powerful empire in the world at the time, then Israel’s God would lose all His authority and the Babylonian god Marduk would be the new God. Thus, Babylon had to be an agent in the hands of a God who was punishing his people for their apostasy.

Does it make the prophetic explanation of the Babylonian exile “false” to recognize that Babylon was going to conquer Israel regardless? No, but I believe the proper way to understand it is that God inspired His prophets to use natural disasters like war and drought to confront Israel about its sin. The events happened because of natural processes and human sociology, which are of course under God’s sovereignty and part of His creation, but the interpretation happened through God’s direct inspiration.

The question is whether in a scientific age, we should be using natural disasters to talk about sin. I don’t think that it represents a spiritual or moral regression for people in our day to find it unbecoming of God to crush elementary school kids in order to express His wrath against sin and instill repentance in His people. I believe that the reason God let the Israelite prophets talk about natural disasters the way they did is because He was meeting His Israelite people where they were. Even though God didn’t “make” the Babylonians conquer Israel, if the Israelites had not interpreted their Babylonian exile as God-ordained, they would have assimilated into Babylonian culture and ceased to exist as a people. So what if we understand the more “civilized” view of God’s relationship to natural disaster not as apostasy but as a greater fulfillment of the theology that understands God to be at His most persuasive and sovereign when He lets humanity crucify Him in the flesh?

I do think that as individuals, we can interpret our lives’ hardships in terms of our personal relationship with God. Psalm 119:71 says, “It was good for me to be afflicted so that I might learn your statutes.” I went through half a decade of severe depression in my twenties. Part of my meaning-making process has been to say that God blessed me with that affliction as part of the preparation for my pastoral vocation and in order to make me exouthenemenos, a “despised one,” a person without worth apart from the grace of God, inside of which I have infinite worth.

That story works for me; I could not cope with a story of my mental health history told entirely in biological terms. However, as a pastor, I do not give myself the authority to tell others how to interpret their tragedies. I can point them to the rich resources of God’s poetry in the Bible so that God can breathe into them the poem that fits. Raw experience is overwhelming to process; we need and we always will use some form of poetry to give our lives coherence.

The question is whether it’s good poetry or bad poetry. God’s poetry misapplied is bad poetry. The tragedy in Oklahoma is not a time to be making theological points about the sovereignty of God. I hope that the people of Oklahoma will find better poetry from God that breathes life and mercy and peace in a difficult time.