I’m at the semiannual Five Talent Academy gathering. It’s an initiative of the Virginia Methodist conference among churches who have covenanted around a set of goals for congregational vitality. Our topic today is worship, led by Rev. Dr. Constance Cherry. I’m seeing a lot of intersection between what is being said here and a book I just started reading by Andy Crouch called Playing God: Redeeming the Gift of Power. And it put a metaphor in my head for thinking about worship that seems helpful to me.

I’m at the semiannual Five Talent Academy gathering. It’s an initiative of the Virginia Methodist conference among churches who have covenanted around a set of goals for congregational vitality. Our topic today is worship, led by Rev. Dr. Constance Cherry. I’m seeing a lot of intersection between what is being said here and a book I just started reading by Andy Crouch called Playing God: Redeeming the Gift of Power. And it put a metaphor in my head for thinking about worship that seems helpful to me.

I often struggle with Christian worship-talk. It’s a lot like Christian sin-talk in that it can provide a forum for holier-than-thou posturing and Jesus-juking (e.g. those other Christians are into “relevant” worship and creating a rock concert experience, but I recognize that God is the true audience and what I care about is whether He approves of what we’re doing, etc). My postmodern cynical sensibilities often poison my ability to hear pious worship-talk without a hermeneutics of suspicion. I know that many people who talk that way are speaking out of genuine conviction. But I would still contend that worship-talk does provide an opportunity for exhibitionist piety whether or not that’s what individual people are actually doing; we can only know our own hearts.

When people talk about the importance of theocentrism in worship and belittle the healing that people can experience there, I often retort in my mind with Jesus’ statement that “the Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27). He did interrupt time that was devoted to His Father in order to heal people; that was the main reason He got crucified — because in the Pharisees’ eyes, He wasn’t theocentric enough.

Jesus also says, “Whoever welcomes a child in my name welcomes me.” (Mark 9:37). And of course He says, “I desire mercy not sacrifice,” which in Jesus’ Matthew 9:13 exegesis of Hosea 6:6 signifies God’s willingness to “eat and drink with sinners.” So our account of theocentric worship must take into account the central message of God’s solidarity with people expressed through Jesus’ Sabbath healing and His insistence that children be allowed to interrupt His important work to receive His blessing. When children worship in their own way and it’s distracting to the rest of us, it may be Jesus asking us, “Are you going to welcome me or not?”

So having given all of this preface, I heard things differently today due to this new Andy Crouch book I’m reading. Crouch defines power as the ability to create a world and its meaning. Power exercised rightly seeks to empower others and draw them into the creative process. Crouch looks at the verb forms God uses in Genesis 1 for His creative process: “Let there be,” which provides the basis for everything that is, and “Let us make,” which is how God introduces the creation of humanity. Even though the “Let us make” is a statement the three persons of the Trinity make to themselves, there is also a way in which it is God’s invitation to us to participate in His creation.

Dr. Cherry frames worship fundamentally as a conversation between God and God’s people. Worship is not just about God; worship is something that happens with God. Cherry points out that Hebrews 8:2 declares Christ to be the leitourgos, literally the liturgist, of our worship community. She also says that the relationship within the Trinity itself should shape our worship ethos. Each member of the Trinity self-empties and glorifies and serves the other members. So worship is our invitation into God’s fundamentally other-regarding reality.

The place where I’ve gotten stuck before in thinking about God presiding over the worship of Himself is questioning whether God really has that kind of ego need. But when I synthesize Crouch and Cherry’s thoughts, I’m able to put a different frame on it. I think about all the times I’ve written a poem or a song and I wanted to share it with somebody. And I’m realizing it’s not inherently narcissistic or egotistical to want to share your creation with somebody else and see that person enjoy it. Maybe it’s a power that can be a gift.

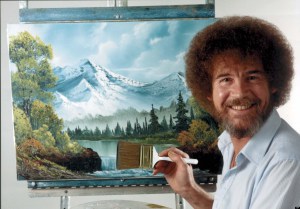

In any case, what if we think of worship presided over by God as the studio of an amazing painter who invites children in to gawk at His masterpieces and then gives them paintbrushes to share in His delight? Jonathan Martin gave me the concept of delighting in God’s delight in his sermon series “Songs of Ascent” two summers ago. It’s not that God has any need to hear how great He is. It’s that He enjoys our joy in His beauty. He’s made and done really cool stuff and He wants to take us on a tour of His gallery. If you read God’s speech in Job 38-41, setting aside its role as a rebuke for a second, what God is doing is taking the reader on a tour of the wonders of His creation. God thinks His leviathans and behemoths are awesome because they’re so utterly wild.

God wants poets and painters and sculptors and singers and thespians and dancers to take up His song and improvise off of His melody. The best way for us to receive the fullness of joy from His song is to forget ourselves while we’re singing it. As long as our creative activity is a performance that’s about our recognition, we cannot enjoy it. It’s stressful; it’s embittering. How do I know this? Because I live it as a poet, a musician, and a blogger whose narcissism has yet to be fully crucified.

I long for the day when I really don’t care about recognition and I’m simply losing myself in God’s song. That’s why worship has to be theocentric. For the song to make me into the incarnation of God’s joy, it cannot be my song. It has to be God’s song that He puts into my heart. The way for us to be joyful creatures and creators is to receive this song and be tuned into its melody every week.

Now here’s another thing. It’s a gift that God is willing to let us serve Him. I don’t think we ever reflect on how presumptuous it is to think that we could serve and minister to God. But that’s the provocative claim we’re making when we we talk about worship as leitourgia, the work or service of the people. The painting studio metaphor works here too. The master painter looks at our childish watercolors that we painted “all by ourselves” (though not really) “just for Him” (even though our egos are all mixed up in it) and He hangs these paintings up on His wall right next to His Mona Lisas.

Nothing is more loving than for a Father who needs nothing to let His children minister to Him. So that’s what we’re invited to do. The greatest artist the universe has ever known is having an open house at His studio; He wants to show us the awesome things He’s made and done so we can delight in them. He wants us to make some things ourselves that He can delight in. Are you ready to make some art with God?