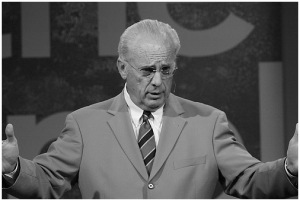

A friend pointed me to Tim Challies’ recent interview with John MacArthur in which MacArthur doubled down on the claims made in his Strange Fire conference condemning the charismatic movement in Christianity. While I don’t have time to consider MacArthur’s scriptural arguments exhaustively, one of the passages he used to support his cessationist view that the Holy Spirit has stopped revealing things to people in the way that happened in Biblical times is Ephesians 2:20. I find his use of this passage providentially ironic and a good opportunity to illustrate how differently we read the Bible.

A friend pointed me to Tim Challies’ recent interview with John MacArthur in which MacArthur doubled down on the claims made in his Strange Fire conference condemning the charismatic movement in Christianity. While I don’t have time to consider MacArthur’s scriptural arguments exhaustively, one of the passages he used to support his cessationist view that the Holy Spirit has stopped revealing things to people in the way that happened in Biblical times is Ephesians 2:20. I find his use of this passage providentially ironic and a good opportunity to illustrate how differently we read the Bible.

Here is how MacArthur cites Ephesians 2:20 in his interview:

When did the gifts cease? One important passage that helps answer that question is Ephesians 2:20, which explains that apostles and New Testament prophets were the “foundation” upon which the church was being built. Before the canon of Scripture was complete, that foundation was still being laid through the apostles and prophets, and through the miraculous and revelatory gifts that accompanied and authenticated their ministries. But once the foundation was laid, those offices and gifts passed away. To follow Paul’s metaphor, the foundation is not something that is rebuilt at every phase of construction. It is laid only once.

It is true that Paul talks about a “foundation” of the prophets and apostles in Ephesians 2:20 (though he doesn’t mention spiritual gifts or give any commentary about their purpose). The question is what purpose does Paul’s metaphor serve. Is Paul making the argument that MacArthur is using him for? In the image Paul is creating, is the important thing about the “foundation” the fact that no impurities should be mixed with it? Is Paul concerned with setting boundaries for the canon? Or has this concern been anachronistically projected onto a metaphor with a very different purpose?

If we look at Ephesians 2:19-22, it gives us enough context to consider the image as a whole:

Consequently, you are no longer foreigners and strangers, but fellow citizens with God’s people and also members of his household, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone. In him the whole building is joined together and rises to become a holy temple in the Lord. And in him you too are being built together to become a dwelling in which God lives by his Spirit.

This section of Paul’s letter is addressed to the Gentiles who had been excluded from the Jewish community prior to Christ’s coming. He is saying that they are now members of the same household and even part of the structure of the temple of God. The purpose of describing the foundation of the apostles and prophets is to say that the Gentiles are part of the same building as they are. So Paul is attributing to them an incredible honor: to become the Holy Spirit’s dwelling-place along with the apostles and prophets. It is amazingly ironic that John MacArthur chose this passage as a proof-text for cessationism because Paul is saying the exact opposite of what MacArthur is claiming!

If God’s temple were built according to John MacArthur’s specifications, it would be a concrete slab of foundation without anything on top of it. Can a foundation with no walls or roof become a dwelling-place for God’s Spirit? Paul seems to be saying pretty plainly here that the temple needs to include the Gentiles who had been foreigners and strangers in order to be a complete building. The most straightforward interpretation of Paul’s metaphor is that the church is a temple which continues to be built.

Sure, the foundation is set. I don’t dispute that. But the foundation is the starting point, not the entirety of everything the Holy Spirit has to say to God’s people. What I tell my congregation is that God teaches us His language in the Bible so that we can hear Him speak in the world around us today. He hasn’t stopped talking. While the vast library of beautiful Christian writing should not be confused with our foundation in the scriptures, we should not despise the riches that have been derived from but ultimately say more than scripture itself. Even writers and thinkers who ferociously disagree like Augustine and Jerome or Whitefield and Wesley each have a lot to teach us without one necessarily being right and the other being wrong.

One of the responses to MacArthur’s conference that I most strongly disagreed with was that of Trevin Wax. He says:

Unfortunately, much of the controversy surrounding this conference seemed to me less like continualists and cessationists making the case for their respective positions and more like postmodern aversion to saying someone could be right or wrong. In fact, some of the criticism launched at MacArthur seemed to imply that MacArthur is wrong simply for being so sure he is right. As if certainty or confidence is at odds with humility.

Wax is applying a very broad brush-stroke with the bogeyman label of “postmodernity” and appealing to a very simplistic conception of truth. Jesus didn’t have a lot of respect for the either/or questions that the Pharisees tried to use to entrap him (“Teacher, is it true or false that the Holy Spirit stopped giving charismatic gifts when the canon was closed?”). He always refused to answer those types of questions directly and usually answered them with questions of his own. That should tell us something about the nature of God’s truth.

Could it be that God isn’t scandalized if different Christians believe different things within a range of orthodoxy according to their giftings, the particularities of their spiritual journeys, and the mission fields to which they have been called? Don’t you give your five year old son a different oversimplification of the same answer that you give him when he’s 12 and when he’s 30? Do you describe concepts in the exact same way to your friend who’s a concert pianist and to your friend who’s an astrophysicist?

When I started out college in the engineering school, I discovered the world of reformed theology that I had never encountered before, because apparently engineering majors who are evangelical really love reformed theology. I spent the first two years of college completely immersed in their world. In engineering, there is one right way to wire a circuit, build a bridge, or design a building, and if you deviate from the one right way by an inch or two, then all of your work has been a complete failure and you have to start over.

When I transferred to the English department, the Trevin Waxes and John MacArthurs were nowhere to be found. I suspect this is because English majors hate anything that smells like reductionism in the interpretation of a work of art. It’s not because English majors are all “postmodern” nihilists making the claim that any literary interpretation is just as good as any other. It just seems disrespectful to truth to claim that I can explain everything about a book in a single page or even in several hundred pages and thus exhaust all of its interpretive possibility. What’s arrogant is not to be passionate about the truth, but to act like I’m the one who has given the final word.

The more truth is in a work of literature, the more impossible it should be to capture its interpretation conclusively (which would indicate there was no reason to read it ever again). If the Bible really is the truth that we believe that it is, it should produce endless conversation that doesn’t seek to cut itself off with conclusions or resolutions so much as to dive into greater depths of epiphany.

It seems that Christians like John MacArthur and Trevin Wax want to figure out the exact right size, shape, and color for the identical bricks that should be stacked up to build the temple of God on top of the foundation of scripture. The Bible never says that we’re all supposed to be the exact same bricks. Paul does say to be careful what we lay on top of the foundation in 1 Corinthians 3:12, and we certainly should. 1 Peter 2:5 uses the wonderfully strange image of “living stones” for what we are. But living stones are not necessarily all the exact same shape and size. 1 Corinthians 12 certainly suggests that every part of the body is supposed to be shaped differently.

I happen to suspect that God doesn’t want a dull, Soviet-looking red brick box of a temple. One of the most beautiful churches I’ve ever entered was the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Washington, DC. The walls are covered in icons of saints. It was immensely more beautiful than the generic auditoriums of suburban megachurchianity.

I happen to suspect that God doesn’t want a dull, Soviet-looking red brick box of a temple. One of the most beautiful churches I’ve ever entered was the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Washington, DC. The walls are covered in icons of saints. It was immensely more beautiful than the generic auditoriums of suburban megachurchianity.

Each of us is an icon of God, made to radiate His image through a unique filter that has been sullied but not destroyed by our sin. As we allow ourselves to be built into Christ, God polishes our icons so that we start to shine again the way we were always supposed to do. I suspect that if you ever have the opportunity to step inside an Orthodox church, you’ll agree with me that God is building His temple with icons, not bricks. And it’s okay with me if John MacArthur is an icon on that wall. I just don’t think he’s the template for the bricks that everyone else is supposed to be chiseled into.