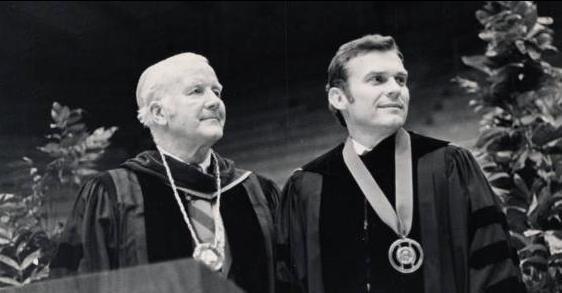

When Martin Luther King, Jr. and his entourage descended on Birmingham, Alabama in early 1963, a group of well-intentioned white clergy leaders including moderate Methodist bishops Paul Hardin and Norman Bailey Harmon published an open letter titled “A Call for Unity” pleading for racial conflicts to be negotiated in in private conversations between community leaders rather than through confrontational street protests. Shouldn’t Christians be able to sit down and have a charitable, civil conversation instead of staging dramatic provocations and shouting at each other with megaphones? It doesn’t seem like an unreasonable question to ask.

In November, 1962, Birmingham had elected a moderate mayor Albert Boutwell in place of the infamous arch-segregationist Eugene “Bull” Connor, who continued to be the Commissioner of Public Safety and basically rejected Mayor Boutwell’s authority altogether. Moderate white and black local business leaders were hopeful about the changes that Boutwell promised to implement and were opposed to the direct action desegregation campaign being organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and local college students. They wanted to give Boutwell time to rein in Connor and avoid sabotaging the business climate of Birmingham in a way that would hurt everybody black and white. But in Bull Connor, the SCLC saw an unhinged racist who would respond to them predictably and provide the perfect controversy to force the federal government to take a stand on civil rights.

This was the environment in which eight prominent white church leaders including moderate Methodist bishops Paul Hardin and Norman Bailey Harmon wrote their letter calling for unity. The letter denounces the demonstrations that were led “by outsiders” (i.e. Martin Luther King, Jr.) and calls for the black citizens of Birmingham to take their lead from “local Negro leadership which has called for honest and open negotiation of racial issues in our area.” It makes the claim that nonviolent direct action is not really nonviolent: “such actions as incite to hatred and violence, however technically peaceful those actions may be, have not contributed to the resolution of our local problems.” It states that the pursuit of racial justice should take place “in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets.”

If the clergy leaders had wanted to, they could have cited a number of Bible passages to support their law and order argument, like Romans 13:1, “Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established.” They could have gone so far as to say that the civil rights protesters were violating the injunctions in Mark 9:42, 1 Corinthians 8:9, and Romans 14:13 not to put stumbling blocks before sinners since Bull Connor’s sin was racism and those cruel protesters were baiting him into sin with their marches. The parts of the Bible that speak like a rulebook take a very negative view of any form of political insurrection. But in the narrative of the gospels, we see Jesus behaving like a political insurrectionist, especially when he clears the temple, so we have to scratch our heads about whether Jesus really obeyed all of Paul and Peter’s teachings about the civility with which good Christians are supposed to behave.

For those of us who weren’t alive in the civil rights era, it’s easy to imagine that black people were just walking down the street minding their own business when the racist cops attacked them with water hoses and police dogs. But that’s not the way it happened during the Birmingham campaign. It was a completely staged provocation. It wasn’t people nonchalantly walking to work or to the voter registration booth. They had no reason to be in the street other than to bait the racist cops into responding the way that King and the SCLC knew they would respond so that the news could snap a photo. Furthermore, the SCLC encouraged children and teenagers to skip school in order to protest. They got their kids to play hookey and put them into dangerous situations all so that they could get the game-changer news photos they were praying for. There was so much that today’s “via media” could have criticized about the most decisive campaign in the course of the civil rights movement.

One could argue that King “bullied” the Birmingham business establishment into desegregation by using children as photogenic martyrs to generate national hysteria instead of letting Birmingham go through a more “naturally” paced, “Spirit-led” discernment process. Indeed, the way that King describes non-violent direct action in his Letter from the Birmingham Jail makes it clear that he saw direct action as a strategic form of “bullying” in order to force change:

Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored… The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.

Putting young black bodies in the streets to have their clothes ripped off by fire hoses and police dogs on national television is not the same thing as making a civil, rational argument for desegregation. King knew that he would never win the white citizens of Birmingham, Alabama, by making enough clear, calm rational arguments that appealed to their human dignity. He was certainly capable of very persuasive clear, calm rational argumentation as he showed in the Birmingham jail letter. But the only way to win in Birmingham was to manufacture a public spectacle that made the whole city look backward and stupid enough to threaten an economic crisis if something weren’t done immediately. And in the end, King’s strategy of nonviolent confrontation simply primed the pump for an explosion of property destruction and street violence in response to the police brutality that finally forced the panicked segregationist businessmen to the negotiating table. In other words, King “bullied” the city of Birmingham into ending segregation if “bullying” means to engage in pressure tactics other than civil, calm rational argumentation.

I’m not saying any of this as a criticism of Martin Luther King, Jr. I’m just saying that the moderates who think that MLK is their guy are sadly mistaken. He could never have lived up to their moderate fantasy of a perfectly civil, perfectly rational approach to social advocacy, because that’s never the way things have happened in the real world. Social change doesn’t happen without the battering ram of manufactured or exploited crises. King understood this. He wasn’t the beady-eyed idealist that his moderate groupies want him to be. He was a radical. He consistently chose revolutionary confrontation over “civil” dialogue. He would probably argue that there could be no genuine dialogue between blacks and whites without first leveling the playing field through revolutionary confrontation.

Even though he insisted upon being the recipient of the violence in every violent confrontation for both strategic and ideological reasons, King deliberately baited racist whites in the South into acts of violence that would unravel the power of segregation. It was basically the perfect living out of a Christus Victor interpretation of the cross. If King had stuck to polite rational discourse, he would have been ignored and cast aside. Too many moderates conflate the distinction between nonviolence and violence with the distinction between civility and confrontation. To call confrontation “violent” just because it isn’t polite does violence to the concept of violence.

In their call for calm and rational negotiations between community leaders in Birmingham, Bishops Hardin and Harmon refused to recognize the fact that not everyone in the room has the same amount of power. The amount of power a person has can be measured as an inverse relationship to the degree to which that person has to make a scene and be a rude “bully” in order to have his/her rights respected. Black women acquired the racist stereotype of being “angry” because they have to raise their voices and speak sharply to get respect from white men who can be as jovial and good-natured as they want without compromising their power. People who have power don’t have to make a scene to get what they want. They can make things happen with a few quick text messages to friends in high places rather than resorting to noisy, messy public demonstrations that ruffle other peoples’ feathers and make them look undignified.

So it’s either naive or cynical to say that you want to stop the extremists of “both sides” from being “disruptive” if one side has insider relationships that preclude the need to be “disruptive.” People with power don’t have to disrupt anything; their agenda is the agenda that gets done.

There’s a difference between limiting yourself to nonviolence and limiting yourself to civility. Nothing about how the Bible describes the actions of the Holy Spirit leads me to believe that the Spirit only moves among people who are treating one another with civility. I think civility should be the default when there aren’t issues of injustice that we’re dealing with. But I don’t think we are forbidden in the body of Christ from using nonviolent direct action that some moderates call “bullying” in order to change the power dynamics so that a real conversation can occur. If you’re offended by that, then please don’t invoke the whitewashed caricature of Dr. King to support your views, because nonviolent “bullying” of the powerful in solidarity with the marginalized is precisely what he did, rightly or wrongly.

Check out my book How Jesus Saves the World From Us!

Please support our ministry NOLA Wesley as a one-time donor or monthly patron!