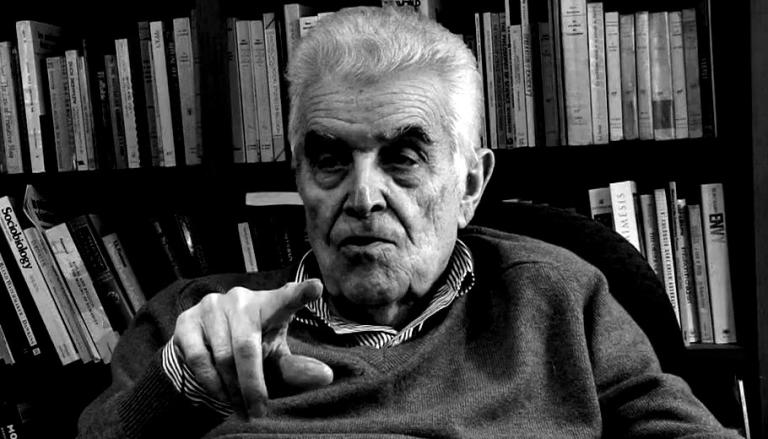

In 2001, my spiritual mentor Bob Holum gave me a book that completely changed everything for me: Rene Girard’s Things Hidden Since the Foundation of This World. I learned the sad news that Girard died this past week, so I wanted to reflect on how his ideas helped Jesus’ cross and the Christian gospel make a lot more sense to me. While Girard’s ideas come from a secular anthropological framework, I think they can be brought into conversation with the Bible and traditional Christian theology in a way that helps progressive Christians who would like to drop-kick Jesus’ bloody cross out of their faith altogether as well as conservative Christians who may be worshiping a toxic image of God created by the logical implications of their ahistorical, impersonal atonement theories.

For those unfamiliar with Girard, his understanding of the basic crisis of human community is framed by two main concepts: mimesis and the scapegoat. Mimesis refers to the way that humans develop desire. We want what we want because we see other people wanting it. We are constantly imitating other people around us. It’s how we learn. It’s also how conflict develops. When we want what other people have and we can’t have it, we get mad.

I’m not sure I agree with Girard that mimesis is everything, but I do agree that our human communities are ravaged by frustrated desires and insecurities related to our desires. These desires and insecurities boil under the surface into a sublimated rage that we sometimes call “bad blood.” We feel it palpably in all of our social interactions. This rage creates a strain on our social fabric until it can be released. When the collective rage reaches a certain threshold of explosiveness, somebody in the community sets it off and that person becomes the scapegoat. Everyone takes out all of their frustration on this person. If it’s a middle school lunchroom, this might take the form of bullying or gossip. If it’s a prehistoric tribe in the desert, the scapegoat is stoned to death or tortured in some other gruesome, horrible way.

Once the rage has been released onto the scapegoat, the community experiences a sense of catharsis which brings peace to their social fabric until they build up enough rage that they need the next scapegoat. For Girard, this process of mimesis and scapegoating explains the ubiquitous practice of ritual violence throughout ancient religions across the world. All of the underlying frustration and anxiety of a community where people have stepped on each others’ toes in thousands of ways can be channeled into the slaughter of an animal (or a human) through which people agree to put their conflict to rest. This ritual violence contains the community’s rage in a relatively healthy way so that their violence doesn’t randomly erupt and stone people to death haphazardly for inadvertent provocations.

The community members could never acknowledge their ritual as a collective anger management practice or else its “magic” wouldn’t work. The only way that sacred violence can work is if it’s named as a mechanism for appeasing the angry god whose wrath everyone in the community feels when the social tension of their built-up sins against each other is screaming out at them. If you’re “conscious” of what you’re doing when you use a scapegoating mechanism to release the rage of a community (i.e. if you make yourself a detached third-person observer), then it doesn’t work. The process requires packaging within a sacred narrative to which every participant is completely subscribed.

This is why Biblical inerrantists cannot embrace Girard’s theory. He provides such an excellent anthropological explanation for Old Testament animal sacrifice that otherwise seems so ridiculously arbitrary, but it seems to require admitting that the Biblical writers are projecting the social tensions of the Israelite community onto an anthropomorphized God whose “emotions” can be assuaged by the “pleasing odor” of burning animal fat (e.g. Leviticus 3:5). To inerrantists, I suspect that a Girardian hermeneutic seems like an inherently hostile, patronizing reading of the Biblical text.

So does it undermine the Bible’s authority to name the emotionally volatile anthropomorphic figure who has the name YHWH in the Old Testament as a metaphorical representation of the very real divine reality that the Israelites experienced together in community? Do we have to believe that an invisible man named God got emotionally angry at Aaron’s two sons Nadab and Abihu for lighting incense at the wrong time in Leviticus 10 and struck them dead? Did Uzzah collapse and die in 2 Samuel 6 because this invisible man named God was actually pissed off at him for trying to protect the Ark of the Covenant? Or do these stories simply represent the best account that Israelites could provide of the wild and sometimes deadly encounters with the divine they experienced in their spiritual pilgrimage?

I think there’s a difference between saying God allows himself to be represented as a violent, emotionally unstable, anthropomorphic tribal deity and saying that God is a violent, emotionally unstable, anthropomorphic tribal deity. And I would contend that I remain within orthodox Biblical interpretation to affirm the former while rejecting the latter. I believe nothing more and nothing less than 2 Timothy 3:16: “all scripture is God-breathed and useful for teaching” but not necessarily factual and straightforward.

What if God’s pedagogical purpose in presenting us with a ruthless representation of himself is to bait us into arguing with the text so that we will become more spiritually mature, Christlike people through our anguish? I certainly can’t say this with any conclusive certainty about any particular text. But to me, 2 Timothy 3:16 doesn’t preclude subversive readings of Old Testament presentations of God. The hermeneutical boundary Jesus declared is that the Law and the Prophets should produce love of God and love of neighbor. Paul expressed this principle similarly to Timothy when he said, “The aim of [biblical] instruction is love that comes from a pure heart, a good conscience, and sincere faith” (1 Timothy 1:5). Any hermeneutic that produces cruel, cold-hearted misanthropes by presenting God as a cruel, cold-hearted misanthrope is a toxic hermeneutic even if it seems faithful to the text.

In any case, I believe that the key to understanding the power of Jesus’ cross is to recognize that God’s wrath and the sublimated rage of a sin-maligned human community are the same thing. Please understand I’m not saying that we’re merely projecting our rage onto a fake God hologram. God is not our invention, but God is not as external to and independent of our spiritual interconnectedness as we are accustomed to thinking. We speak of God anthropomorphically because of the limitations of human language. It is inadequate to God’s reality to name God as a phenomenon rather than a person, which is why the Biblical writers must make the slightly less inadequate choice to describe divine phenomenon as though God were an invisible man. But if God is in fact the one “in [whom] we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28) and our bodies are in fact “temple[s] of the Holy Spirit” (1 Corithians 6:19), then when our idols, lusts, anxieties, and tempers cause violence to erupt in our community, we ourselves embody the wrath of God.

This doesn’t mean that God sanctions our violence any more than God sanctioned the violent conquests of the Babylonian emperor Nebuchadnezzar or Assyrian emperor Tiglath-Pileser whom the Israelite prophets named as the embodiment of God’s wrath against Israel. It means that our violence channels a lack of harmony, justice, and peace that refuses to be silent. God’s wrath is the violence by which the lack of harmony, justice, and peace in the world is made known.

This understanding of wrath is entirely consistent with the longest discourse on God’s wrath in the New Testament, Romans 1:18-32 which opens by saying, “The wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and wickedness of those who by their wickedness suppress the truth.” Paul doesn’t follow up this verse by listing a series of natural disasters by which an angry anthropomorphic God reacted to sin. Instead, the wrath of God is revealed to be sin itself in increasingly violent, community-wrecking manifestations.

When we talk about God’s wrath, we are not talking about the emotional anger of an invisible man named God. We are talking about the way that reality refuses to allow untruth and disharmony to stand, no matter how powerful the perpetrator. When divine truth is violated, it responds violently. As Cain learned after murdering his brother Abel, we cannot sweep our injustices under the rug by saying, “I am not my brother’s keeper,” because the blood of Abel “cries out from the ground” (Genesis 4:9-10).

The rage that cries out from the ground is God’s wrath. The Bible warns that if we violate truth and justice, the land in which we’re living will “vomit [us] out” (Leviticus 18:28). This is not because God is an invisible man with a remote control in the clouds who presses earthquake and drought buttons to punish people for engaging in debaucherous, barbaric deeds. It’s because debaucherous, barbaric deeds destroy community and the thing we call community is where we experience the mysterious reality we call God. God’s wrath is the violent infection of a human community in septic shock.

So here’s where Jesus cross comes into play. For centuries, Israelites dealt with the bad blood of God’s wrath in their community through an elaborate system of animal sacrifices that sort of worked but ultimately didn’t. Jesus’ cross is the sacrifice of sacrifices. It places God as the victim of sacrifice rather than merely the recipient. The cross “works” to the degree that Christians are able to direct all of our sublimated rage and guilt onto the body of Jesus, which is to say that we name all of the ways that we have crucified others and been crucified ourselves as nails in Jesus’ flesh. That is what it means to put my “faith” in the blood of Jesus; it means I hand over every sin I have committed and every other person’s sin against me to Jesus’ cross where it is absorbed and obliterated.

Jesus’ cross is supposed to be bloody and horrifying because our sin is bloody and horrifying even when its wrath is manifested far away out of sight and mind in the shantytowns and sweatshops of the Global South which bear the weight of our “first world” greed. We should hang graphic crucifixes (not falsely emptied crosses) on our walls and look into Jesus’ eyes as a daily devotional practice to meditate upon the ways that his blood is solidarity both with us as sinners and with the victims of our sins. Perhaps we should surround our crucifixes with pictures of suffering in the pueblos crucificados where Jesus is crucified today.

This is where I disagree with many of Girard’s interpreters. Jesus’ cross is not our “graduation” from the ongoing reality of mimesis and scapegoating. It is the ugliest farce of bourgeois liberal privilege to pretend that we live in a world where blood doesn’t happen anymore. We can’t just “update the metaphor” into something without blood because we’d rather not think about the unpleasant, messy ways the wrath of God is being revealed in Ferguson or Hebron today. Now more than ever, in our synthetic, post-physical “first world,” we desperately need to face the completely bloody violence of Jesus’ cross so that our sin can continue to be named as the murder of our messiah whom we have never stopped crucifying.

Of course, it’s not just queasy, privileged liberals who wipe the blood off of Jesus’ cross. The conservative evangelicals who make Jesus’ cross into an abstract economic transaction are likewise stripping Jesus’ blood of its atoning power, particularly in traditions where the “Lord’s Supper” is a side show to the diva Bible teacher’s 45 minute proclamation. Any ahistorical, impersonal understanding of sin as mere demerit against God and Jesus’ cross as mere transaction belongs to a deformed Christianity which has no concept of Eucharist. Any atonement theory which does not centrally incorporate the regular practice of eating Jesus’ body and drinking Jesus’ blood as its mechanism of delivery is not authentic atonement. You cannot get to the Lord’s cross except through the Lord’s table.

I don’t know exactly how to talk about it, but I know I need to eat Jesus’ body and drink his blood to be made clean. Yes, this makes me sound like a cannibal and a vampire, but it’s what I need as a physical creature in a world where my sin contributes to demonic realities that shed physical blood. I’ve actually arranged my schedule so that I receive Eucharist every day except Tuesday and Saturday. The Eucharist is my pharmakos, to use Girardian language. I don’t know whether any of this makes any sense or if it faithfully represents Rene Girard’s thought, but I’ll always be grateful that Pastor Bob gave me that book because it was the start of an incredible journey.