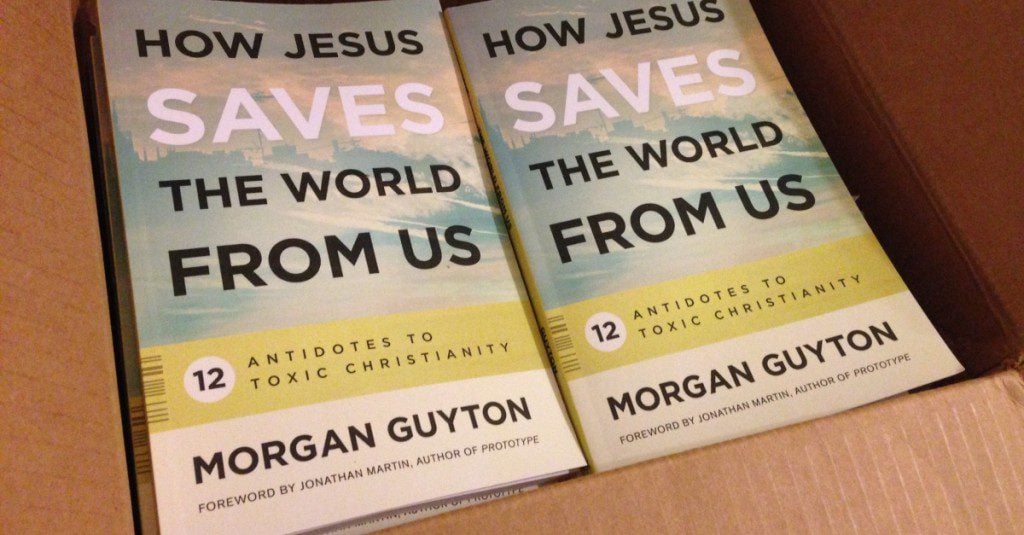

From now until the release of my book How Jesus Saves the World From Us, I’m going to write twelve blog posts covering the themes of my twelve book chapters. My second chapter “Mercy Not Sacrifice” talks about the way that Jesus saves us from the miserable life of always keeping score by inviting us into the kingdom of his mercy in which there is no score because everyone is wrong and God gets all the credit for loving us anyway.

There is nothing more American than keeping score. We are the most competitive, achievement-oriented society on the planet. Our kids are indoctrinated with this attitude from the time that they’re old enough to kick a soccer ball. Ingrained into this world of competitive achievement is the value of sacrifice. Because the way to win is to sacrifice hours and hours of time doing your homework, practicing, and refining your skills, whether the task is basketball, violin, or chemistry. When you sacrifice, you deserve to win.

That’s the basic promise of the American Dream. If you work hard in school, you will get a good job that will enable you to support a family when you graduate. Which means that the corollary is also true. People who don’t have good jobs that enable them to support their families have failed probably because they weren’t willing to make all the necessary sacrifices. This assumption has guided American political sensibilities for the past thirty years. People who make sacrifices deserve every penny that they earn, and not a single penny of theirs should reward and enable the laziness of people who weren’t willing to make sacrifices and thus find themselves in need.

One of the best illustrations of this mentality is the classic Walt Disney cartoon film The Grasshopper and the Ants. While all the ants are working hard to store food for the winter, the grasshopper is playing on his fiddle (which isn’t work because music doesn’t count as a legitimate vocation). When winter comes, the grasshopper doesn’t have any food so he has to beg his way into the ant colony to get food. I wonder what would have happened if the grasshopper were making capitalist propaganda films (another form of art aka “laziness”) instead of working hard to gather food for the winter, but anyway.

There is a lot of value in sacrifice. Without a willingness to make any sacrifices, we become completely self-indulgent people controlled by our appetites. Sacrifice gives us discipline and refines our character. The problem is when we make our sacrifices transactional, which is how our market-based economy trains us to see everything. The spiritual poison happens when we keep score about our sacrifices and use them to put ourselves above other people.

Jesus was criticized by the austere religious authorities of his day for hanging out with sinners, i.e. people who didn’t make all the stringent sacrifices commanded by the 613 laws of Torah. He said in response, “Go and find out what this means, ‘I desire mercy not sacrifice'” (Matthew 9:13). Jesus was quoting Hosea 6:6. These words represent a revolutionary paradigm shift in the understanding of what God’s expectations for humanity are. Everything that differentiates the Christian gospel from every other religious system is summarized in this five word sentence. That’s why Pope Francis has declared this the year of mercy. Christians without mercy are not really Christian. It should be the one thing that is constitutive of our identity before any talk of doctrinal propositions.

For the religious authorities who fought with and ultimately crucified Jesus, God expected very stringent sacrifices of his people not for any sake other than his glory. It was transactional. If you offended God by sinning, you had to pay him back by performing a ritual and sacrificing an animal of some kind. The purpose of sacrifice was to pay back all the debt owed to God. Indeed, many Christians today have exactly the same understanding of how God works that Jesus’ enemies did. For them, Jesus’ cross has an entirely abstract, transactional purpose; it pays back the debt of sin through sacrifice. If you sign onto the Jesus payment plan (however you’re supposed to do that officially), then you get to go to heaven; otherwise you have to pay back your own debt to God for your sin by suffering in hell forever. One could not find a better way to conform the gospel to secular American capitalist values.

While it’s certainly true that spiritual debt is one of the metaphors used to explain the purpose of Jesus’ cross, if we take the phrase “I desire mercy not sacrifice” seriously, then an entirely different meaning for Jesus’ cross emerges. What if instead of affirming the fundamental validity of keeping score when it comes to sin, Jesus’ sacrifice is the means by which all of our score-keeping is invalidated and replaced with a culture of mercy? What if it’s not God who needed to get paid in blood for our sin but us? What if what Jesus sacrifice earns is freedom from transactional sacrifice for those who believe that he really did “pay it all”? Jesus’ cross was definitely a sacrifice, but its purpose was to eliminate sacrifice forever, at least in its transactional form. Jesus’ cross makes it possible for me to say I can never repay whatever debts I owe for all the wrong I’ve done, but now I live under God’s mercy. The evidence that I have actually accepted God’s mercy is that I become God’s mercy in the lives of other people.

Jesus told a parable called the Prodigal Son about two brothers. The younger one was a good-for-nothing who asked his father for his share of the inheritance, ran off to the city, and wasted all of it. The older brother worked hard and made sacrifices all of his life. When the younger brother comes to his senses and returns home, the father prepares a great feast for him. The older brother gets really angry and refuses to come into the feast. When his father goes to find him, he lays into his father, saying “I’ve worked for you like a slave.” In other words, his sacrifice makes him feel entitled to judge his father’s mercy. The older son will always be a slave to the degree that he hates his father’s mercy.

If the Prodigal Son is representative of what communion with God ultimately looks like, then the litmus test of whether or not we “get into heaven” is whether or not we can accept God’s mercy on people we don’t consider worthy of being there. If our score-keeping and sacrifices fill us with bitter entitlement like the prodigal son’s older brother, then we will stay out of heaven in the outer darkness gnashing our teeth.

The father in the parable gives a beautiful and profound response to his eldest son’s complaint. He says, “Everything I have is yours,” which is a gentler way of saying, “Everything you have is something I gave you.” In other words, the father has already shown the older son mercy; he has been showing mercy to both of his sons from the beginning. Whatever discipline and success the older son has achieved is a product of his father’s prior mercy through his patient teaching and unconditional love. When we understand that everything we have and everything we’ve accomplished is not a reward that we’ve earned but a gift of God’s mercy, then we can join the heavenly banquet that the older brother was refusing to enter. Mercy is what heaven looks like. It’s how Jesus saves us from keeping score.

Please like my facebook author page!