When I was fifteen years old, I was a huge fan of Rush Limbaugh. I hated “feminazis,” and I thought that political correctness made the world oppressive and inauthentic. But I wasn’t racist because I didn’t say the n-word. So I’ve been thinking about what I would say to my fifteen year old self if I had been at the North Carolina United Methodist Pilgrimage youth retreat this past weekend. A racist incident took place, and the response made some of the white youth feel unfairly shamed. This is why our youth need a solid theology of Jesus’ cross. Let me explain.

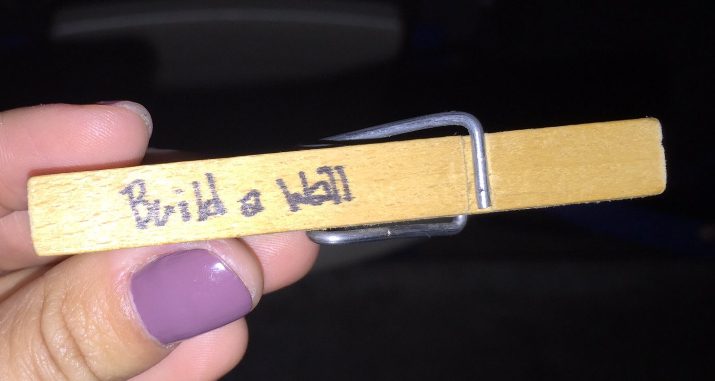

First, here’s what happened. A group of students wearing red Trump hats clipped a message on a Latino youth that said “Build a wall.” After Stacy Guinto-Salinas, the pastor of the Latino youth got on the stage and told the crowd that her youth group didn’t feel welcome, she was excoriated by not only some of the white youth but also their adult leaders for ruining a worship service by bringing politics into the mix and supposedly accusing all Trump supporters of being racist. The North Carolina state leadership then posted a Facebook message that emphasized its regret that white people had been offended and put the onus on Stacy for having “brought up” politics.

I wanted to see where the backlash was coming from, so I watched a video of Stacy’s testimony. Here’s the closest I could find to what she was accused of saying. She said that “red hats” representing a political candidate who had said disparaging things about her community made her youth group feel unwelcome. She challenged those who were wearing these red hats to take them off so that everyone could feel welcome. She said the message of the red hats wasn’t the message of the gospel. In other words, don’t bring a partisan political message into a Christian gathering after a very contentious election, since Jesus’ gospel is about saving the world, not “making America great again.”

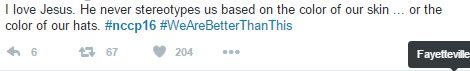

Stacy never used the word “racist.” Nor did she refer to Donald Trump by name. But some of the white students and adult leaders in the audience received her expression of her youth group’s pain as an unfair judgment against them. Several hundred of them walked out on her speech, and many others lashed out on social media. The following is a sampling of their tweets.

So why was there such a gap between what Stacy actually said and what many white youth in the crowd heard in her words? I could be callous and say something disparaging about them being fragile white millennial snowflakes. That was the blog post I was originally going to write. But God told me to do something different this time. Because I remember being hurt the way they were. When I’ve felt like somebody was judging me for being racist, it was a very painful experience. It was also an experience God used to help me grow.

It’s very hard to hear other people talk about their pain publicly when you are even slightly, possibly implicated as a cause of that pain. It feels unfair to have to sit through that as a captive audience. I get that. We live in a paradoxical universe right now. We are incredibly uncomfortable with conflict in live interactions, while we are incredibly comfortable raging out on our smartphones in response. And this is why we need a good theology of Jesus’ cross to save us.

A critical aspect of how Jesus’ cross saves us is through our discomfort of facing the reality that our sin keeps on crucifying him. Every time I hurt another person, I crucify Jesus, because his cross is an eternal reality. When we reduce Jesus’ cross to a poignant metaphor for use in angsty praise songs or a math equation for a tacky Powerpoint about four spiritual laws, we have lost hold of its power. Its power lies in naming the evil of our sin so we can be convicted and repent.

The cross exposes the world’s sin. Conviction is a crucial part of its atonement. Jesus’ atonement doesn’t hide what is ugly; it makes it safe to bring the ugliness into the light so it can be transformed into beauty. John 3:19 says “light has come into the world but people loved darkness rather than light because their deeds were evil.” The cross provides light, not darkness. Though our sins are “covered” by Christ’s blood, that covering is the opposite of hiding what is ugly in order to preserve a veneer of positivity in our Christian community. Hebrews 10:19 tells us that Christ’s blood should give us confidence to face the truth. What Christ’s blood protects us from is not the discomfort of facing our community’s sin, but the cowardice of hiding from it.

When I look at these students’ tweets, I see a frustration that Pilgrimage wasn’t the uplifting mountaintop experience they thought it was supposed to be. As a high school student, I definitely would have been irritated and tweeted something similar. But this is precisely where the critical lesson needs to happen. True cross-centered worship is repentance, not positivity. It is not manufactured goose bumps, but the disorientation of being undone by God and brought into the terrifying exhilarating vulnerability of liberation from our ugliest secrets.

When anyone’s sin is exposed in our presence, it’s embarrassing and painful. I don’t think it’s possible to hear somebody talk about pain they have experienced in a community without feeling personally judged, regardless of how or whether they assign blame at all. But this does not put the onus on the person sharing their pain to tiptoe around our emotional sensitivity and identify wrongdoers with perfect precision. Sin is always complicated and it’s always a collective reality. It’s not just a question of which teenagers brought partisan political propaganda into a Christian youth space. Who didn’t stop them? Who failed to educate them? Who was too caught up in their personal cliques to make sure that the Latino students were welcomed and loved?

Everyone at Pilgrimage was part of the sin of unwelcome, just like everyone in humanity crucified Jesus, not just the soldier physically driving the nails into his flesh. What does Jesus say about the standard for loving our neighbor? “Be perfect as your Father in heaven is perfect.” Short of perfect love, none of us is without sin. Romans 3:23 defines sin as simply “falling short of the glory of God,” which we all do. When people are offended that the naming of sin puts a blight on their positive mountaintop experience, that offense is what Jesus’ cross looks like.

The fact that so many white teenagers in that coliseum lashed out in response to what Stacy said is actually a good sign. It means that they were convicted by the Holy Spirit. But they need some guidance on how to grapple with the awkward discomfort of hearing someone describe pain they were indirectly, collectively a part of. This is where their youth pastors have either risen to the challenge or failed the gospel.

Now here is a second aspect of our theology of the cross. Jesus tells us to take up our crosses. One place the apostle Paul interprets how we are to emulate Jesus’ cross in our lives is Philippians 2. Two of the most important and most difficult verses say, “Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves. Let each of you look not to your own interests, but to the interests of others” (Phil. 2:3-4).

One aspect of taking up your cross means allowing situations not to be all about you and your feelings. That means if other people are upset, you are unconditionally present to their pain, whether you think their response is reasonable or not, whether you feel unfairly judged by them or not. Because it’s not about you. It’s about making them feel safe and loved. Your cross is sitting uncomfortably with someone else so that they can feel safe and respected by you, no matter what they are saying. I’m not saying this is easy to do. It’s very hard. But it’s the goal that we are striving towards.

People who have embraced the justification of Jesus’ blood on the cross do not have a problem absorbing the discomfort of others’ pain, judgment, or anger, because they do not need to justify themselves. They know they have contributed to the world’s sin, and they know that they are forgiven. That’s what it means to be saved: having the assurance of Christ’s atonement that liberates us from the exhausting responsibility of arguing that we have always been right. Assigning blame perfectly is no longer a relevant question for those who are justified by Christ. They simply love unconditionally and receive others’ pain graciously to see if there is an edifying lesson from God.

Taking up your cross means empathy is your first thought. My greatest concern is the row of Latino students who were behind their pastor on the stage while she stood up for their dignity and watched hundreds of white people walk out of the room in protest. Do you think any of those Latino students are going to want to come back to Pilgrimage again? If you’re a white United Methodist youth in North Carolina, what are you going to do about that? If you’re a pastor, how are you going to take up Jesus’ cross and respond with courage? To be silent because you’re afraid of others lashing out is the opposite of what Jesus’ cross looks like.

Check out my book How Jesus Saves the World From Us!

Subscribe to our podcast Crackers and Grape Juice!

Support our campus ministry NOLA Wesley!