I decided to get back on the blog for Good Friday since I’ve been thinking a lot about Jesus’ cross lately. Growing up in white evangelicalism, I received a very distorted understanding of the cross. I think the distortions I’ve encountered are largely a product of turning Christian salvation into a white middle-class consumer sales pitch for afterlife insurance. And I believe that the good news is actually much better news than what many of us have been told. So here are five things I think Christians need to get right about the cross for it to be more than a suburban consumer product or a shield decoration for imperial conquest.

1. Jesus’ cross is not a math problem

To many Christians, Jesus’ cross is a simple math problem. This can ultimately be traced back to the 11th century teaching of St. Anselm in Cur Deus Homo. To summarize very roughly, Anselm wrote that since God is an infinite being, then the slightest infraction against God’s commands is infinitely offensive to him, so the blood of the infinite being Jesus is required to cancel out the infinite debt of our sin. He made it a completely impersonal, abstract math problem.

Perhaps Anselmians will call this a caricature of his teaching. Fine, but it’s a ubiquitously popular caricature and the implications are hideously nihilistic. Most of the people who think this way have never heard of Anselm. They just know that anyone who says shit once in their life deserves to be tortured in hell forever unless they accept Jesus as their personal Lord and savior because God expects perfection and all sins are equally offensive to God and God can only forgive your sin with the arithmetic of Jesus’ blood + your faith. Maybe you have a more eloquent, nuanced account of penal substitutionary atonement in your ivory tower, but Pastor Bobby at the 5000 member Bible Cathedral on Flower Bluff Highway has a Power Point that makes it simple enough for a second grader to understand.

When I read the stories of evangelism in the early church in Acts, I don’t see apostles like Peter and Paul going around hawking afterlife insurance or talking about four spiritual laws. In the first evangelistic sermon in Acts 2, Peter converts 3000 people to Christianity by saying, “God has made him both Lord and Messiah, this Jesus whom you crucified.” Verse 37 says the people were “cut to the heart” by his words, and they asked to be baptized. In other words, Jesus’ cross convicted them and that’s what made them become followers of Jesus, not their fear of being tortured forever. Its primary function was not to fulfill God’s esoteric, abstract moral bookkeeping, but to cut people’s hearts.

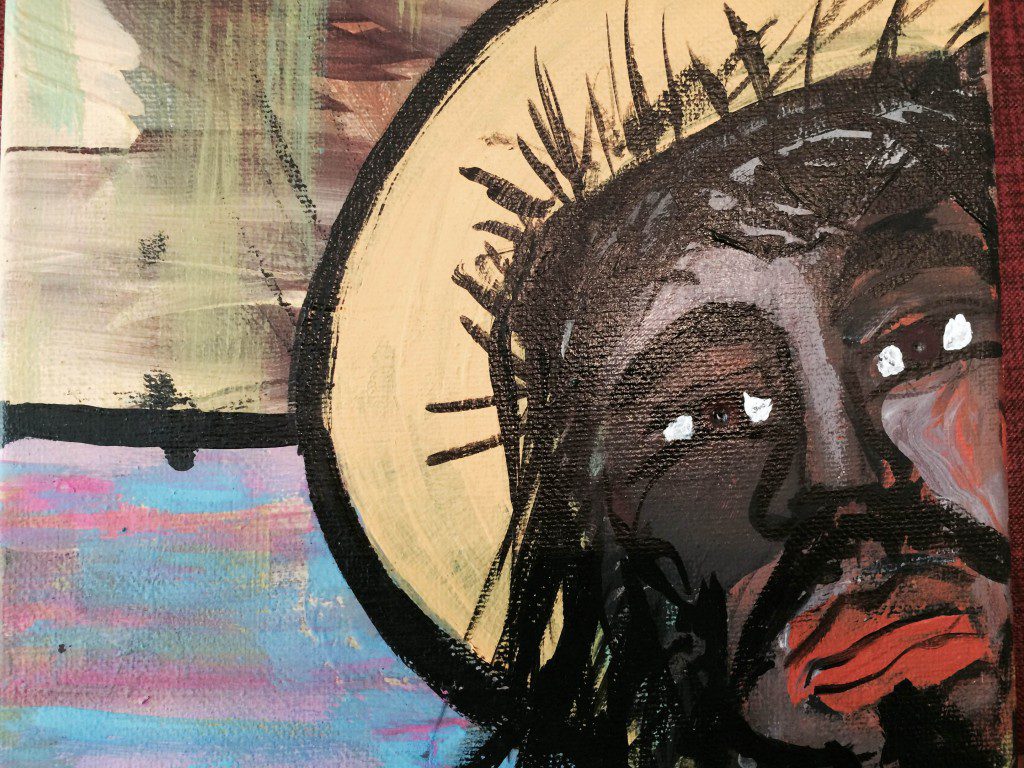

The heart-cutting of the cross has continued to happen throughout the church’s history, but it doesn’t show up in the thousands of pages of atonement theory that have been written over the centuries because its nature is not theoretical but experiential. The cross cuts people’s hearts when people encounter it through liturgical and devotional practices that make them meditate upon the suffering of Jesus. To the degree that these liturgical and devotional practices have been removed from the church (as in low church white evangelicalism), the cross is more vulnerable to nihilistic abstraction and caricature.

The cross is supposed to elicit our pietas, the Latin word that gets translated as both pity and piety in English. If we don’t feel any sense of pity for Jesus’ suffering on the cross, then it’s worth contemplating whether we have ever actually encountered the cross. Interestingly, the word piety has evolved to become the word we use to describe theologically correct posturing, the kind of prattling of cerebral theological maxims many white evangelicals do when they’re talking about the cross as a math problem. But the original meaning of piety had to do with devotional acts that move the heart. If our hearts have not been cut by the cross, then perhaps we have yet to receive all that Jesus has to offer us from it.

2. Jesus’ cross is an invitation to take up our crosses

So much white evangelical theology of the cross focuses on it being a substitution: Jesus taking the rightful punishment for our sin. But when Jesus himself describes the cross, he does so as an invitation: “Whoever wants to be my disciple, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me” (Mark 8:34). I’ve never understood why this invitation gets disconnected with the crucifixion Jesus personally suffered, especially when the apostle Paul makes it clear that Jesus’ cross is something that culminates in our participation: “I have been crucified with Christ so it is no longer I who live but Christ who lives within me” (Galatians 2:20).

Yes, our participation is mostly mystical and metaphorical with some exceptions, but it’s very important that Jesus’ cross invites us into a way of life rather than solely doing something for us. It’s true that one dimension of Jesus’ cross is his sacrificial offering for our sins. But that isn’t done for the sake of God’s abstract moral banking system. It is done to invite us out of our defensive self-justification and into a life where we have the freedom to be wrong and completely honest about our flaws.

Taking up my cross and following Jesus can mean multiple things. The cross is God’s triumph over public shame that has been stripped of its power. So one aspect of taking up my cross is entering into a life where I’m not ashamed of my mistakes and I deal with them openly in community with other unashamed sinners who are being perfected in God’s love. This means accepting that Jesus has justified me unilaterally and unconditionally so I stop hiding my sin from others.

Another aspect of taking up my cross concerns my self-denial. Taking up my cross means that I don’t have to be right and win every argument. I don’t have to sabotage every conversation I’m a part of with my white male need to preserve my self-dignity at all times. This is related to the first dimension of having been justified by Jesus. It’s a little more tricky because not everyone has an equal need to deny themselves. Many black women are already forced to deny themselves unhealthily in community in order to accommodate sensitive white male egos like mine. I need to hear Jesus’ command to deny myself and part of that self-denial is letting go of expectations for other people to do the same.

A third aspect of taking up my cross has to do with the political risk of following Jesus. In Mark 8:35, he says, “ For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it.” Now there’s a lot of mischief in white evangelicalism over this aspect of taking up our crosses. It’s tempting to find un-Christlike ways of soliciting the world’s persecution like making your stand against gay marriage the entirety of your religious practice and witness.

When we look at who Jesus lost his life for standing with, it was not because he supported the religious insiders in their condemnation of sex workers and tax collectors that he got crucified. It was because he stood with the sex workers and tax collectors and condemned the religious insiders. So taking up our cross means walking with those who are despised and crucified by the religious insiders in our world. It means risking ostracism and perhaps physical violence. I have a good friend whose decision to found an organization that promotes human rights for queer people in Africa has caused him repeated threats on his life and bouts of physical violence; that’s what taking up a cross looks like.

3. Jesus’ cross is what religious authorities do to God

Jesus foretells his crucifixion 3 times in the gospel of Mark. In Mark 8:31 he says “that the Son of Man must undergo great suffering, and be rejected by the elders, the chief priests, and the scribes, and be killed.” In Mark 9:31, he says, “The Son of Man is to be betrayed into human hands, and they will kill him.” In Mark 10:33, he says, “The Son of Man will be handed over to the chief priests and the scribes, and they will condemn him to death; then they will hand him over to the Gentiles; 34 they will mock him, and spit upon him, and flog him, and kill him; and after three days he will rise again.”

Notice the importance Jesus gives to the agency of religious authorities in his crucifixion. They are the ones who reject, betray, and hand him over. He doesn’t say the Son of Man must be killed to satisfy the wrath of his Heavenly Father. In the white evangelical account of the cross, the role of religious authorities is air-brushed out of the picture. God is the crucifier of Jesus because it’s God’s plan to pay himself back for humanity’s sin. Even if we describe the cross as being part of God’s plan for humanity’s redemption, when today’s religious authorities minimize the agency and sinfulness of the religious authorities who arrested Jesus, it’s a revealing distortion of the story.

When Colossians 2:15 says about Jesus’ cross that “he disarmed the rulers and authorities and made a public example of them, triumphing over them in it,” this triumph is not just over abstract invisible spiritual forces (as white evangelicalism often interprets it), but over flesh and blood religious authorities who thought their duty to God demanded that they execute Jesus for blasphemy. Part of the purpose that Jesus’ cross accomplishes is to disarm religious authority. It is God forcefully rebuking people who thought they had the authority and exclusive right to speak on his behalf.

I don’t think God’s relationship with the religious authorities who tried to co-opt God in Jesus’ day is that different than God’s relationship with the religious authorities who try to co-opt him today. Jesus continues to be crucified by the people who supposedly worship him but have turned his religion into a means of propping up their own hegemonic control over others. When John 1:11 says, “He came to his own and his own people would not accept him,” that’s describing what happens to Jesus today as much as it describes Jesus 2000 years ago.

It makes sense that Christian religious authorities would want to minimize the degree to which the cross calls out religious authority as such, but it’s a critically important part of the story.

4. Jesus’ cross is insurrection, not empire

When European conquistadors planted crosses on the beaches of the Western Hemisphere, they could not have been more at odds with the authority that Jesus establishes through his cross. Their authority was the authority of the swords they used to exterminate indigenous people, not the authority of Jesus’ blood on the cross. It is pretty well impossible for Christians to have a direct experience of Jesus’ authority because the church’s institutional authority will always be an intermediary.

Insofar as Jesus’ blood has authority, its authority is insurrectionist in nature, not imperial. What I mean by this is Jesus’ blood does not intimidate us into submission the way European conquistadors used their guns and swords to force indigenous people into Christian baptism. The power of Jesus’ blood doesn’t look anything like the power of an institution that can have people burned at the stake or ostracized from their community. On its own, Jesus’ blood can only convict and haunt us into solidarity with God’s movement. It is the power of truth unadorned with any semblance of force. As an insurrectionist call to action, it is indeed very powerful in a completely different way than empire is powerful, but the imperial institutions that paint it onto their shields have entirely betrayed it.

I think this is a very important distinction because followers of Jesus should only use cruciform power to win others into alignment with Jesus. Insofar as we use coercive political power to advance our agenda, then we are no longer doing Jesus’ work. We are saying yes to the devil’s temptation that Jesus rejected when the devil offered all worldly power if he would just worship him. I think that pursuing worldly power for the sake of putting ourselves in control is the way to worship the devil. The power of the cross is completely antithetical to that.

5. Jesus’ cross belongs to the crucified first and foremost

The white evangelical account of Jesus’ cross operates as though God’s heavenly courtroom only has defendants and no plaintiffs, because it’s a gospel that’s tailored to oppressors who don’t want to be held accountable, not to their victims. God is the only plaintiff and the only crime is dishonoring his authority so Jesus takes the punishment for this abstract crime and the transaction is complete. No need to have any earthly reconciliation or restorative justice.

This is very different than the way black slaves in the American South came to see Jesus’ cross. Think about the song “Were you there when they crucified my Lord?” That is how people who have been crucified sing about Jesus’ cross. They sing with compassion and pity for each of Jesus’ wounds. They sing about Jesus as one who shares entirely in their unjust suffering, like he’s a fellow slave who got lynched by the plantation owners. For them, Jesus’ cross is primarily God’s solidarity with their victimization at the hands of others’ sin. Certainly, they understand themselves as sinners also, but Jesus’ solidarity with their victimhood is primary.

It’s true that the message of solidarity from Jesus’ cross is more sublimated in the biblical text. Peter and Paul both use Jesus’ suffering as a basis for encouraging followers who are suffering persecution, but the metaphorical comparisons to temple sacrifice and the Passover make the atoning aspect of the cross seem much more prominent. Yet, I would contend that even Jesus’ capacity to serve as my sacrificial lamb is efficacious to the degree that I recognize him as the ultimate victim of my sin rather than just the whipping boy who receives the punishment for it. In other words, Jesus’ solidarity with the victims of my sin in receiving the violence of my sin is a critical aspect of how I am liberated from being imprisoned by my sin.

I would suggest that the degree to which I have been transformed by Jesus’ cross is measured by the degree to which I care more about the healing and restoration of the victims of my sin than my own need to stop feeling guilty. Many Christians want their guilt to be erased without having to go through the hard, slow work of reconciliation. The removal of guilt is for the purpose of empowering us to be reconciled.

When I’m focused on others’ healing and restoration, I stop obsessing over my guilt. With this in mind, I think that victims of sin in their capacity as victims are the ones for whom Jesus’ reconciling work on the cross is most important, especially since their relevance has been completely erased by bad atonement theory that makes us all only defendants. Jesus’ cross says to the crucified, I see you, I love you, and I suffer with you. They should be the cross’s primary interpreters.