It may shock many Christians spuriously familiar with passages of Scripture that even their favorite Bible stories and passages are neither obvious nor clear.

So many Bible readers claim that the meaning of many verses are obvious. A day does not go by where I do not read someone saying, “the Bible clearly says…”

But is the Bible ever clear for Western, 21st century eyes? Is the Bible ever obvious? Look here at this verse:

John 3:16

For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him might not perish but might have eternal life.

This is the most famous of all Bible verses. You cannot escape seeing it on large signs in many sporting events and everywhere besides. But what does it really mean? Many American Christians believe that the meaning is plain, obvious, and clear.

So let’s break that verse down by means of questions. Who or what is meant by “God”? What is meant by “loved”? And what exactly is meant by “the world”?

It’s Obvious that “God” means…

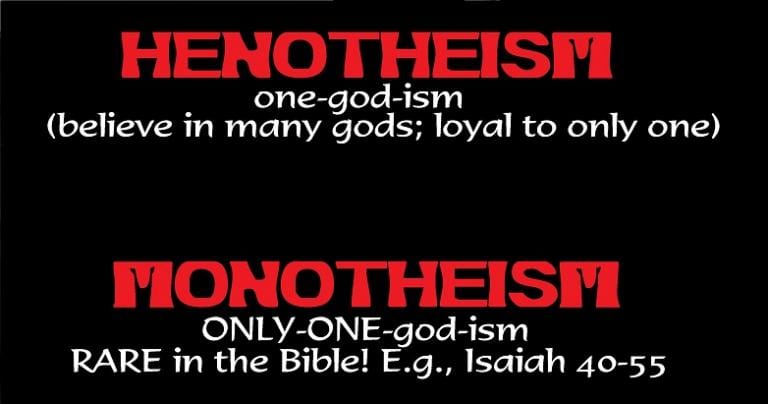

Does the human author conceive of “God” (ὁ Θεòς) in the same way a Trinitarian Monotheist understands “God”? How long did it take to unpack and work out a theology of the Trinity? Was the author known to us as “John” around for that?

It is one thing to say that the theological idea of the Trinity can be found in seed-form in Scripture and only later evolved, growing out over fifteen centuries from these roots, most slowly and often unevenly. It is quite another thing to claim this highly-evolved doctrine of the Trinity can be found clearly in the Old and New Testaments and from there proof-texted! No individual passage of Scripture or Frankenstein-like combination of verses (rippled bleeding from the corpses of multiple texts) reads out a theology of the Trinity.

Clear Teaching about Not-So-Clear Mystery

We Catholic Christians believe that the Spirit guides (not coerces, not dictates to) the Church. Many hold that Holy and Absolute Mystery called “God” has been disclosed in Jesus so definitively that fundamental error in how the Church perceives, interprets, and doctrinally expresses the experience of “God” in faith is impossible.

And yet distortion certainly exists in secondary matters of belief. Ambiguity is always present with us because of limited human language and “God” being ineffable. That’s just how life and mystery are, folks! We must grapple with revelation ever with close bedfellows, distortion and ambiguity!

Indeed, we have grappled through long centuries of heresies and schisms, through the crucible of imperial politics and identity crises, through bitter disputes and exiles. Here we trace the thousand-plus years of theological evolution through various conflicts. Our study shows us essential movements without which our belief would be different: the geniuses of the Cappadocians; the promotion of the Trinity’s liturgical prominence in Benedictine monastaries of the 9th and 11th centuries; Pope John XXII in 1334; and many other key steps.

We ought not delude ourselves that this theological freight was on the mind of “John” the author of the Fourth Gospel when he wrote down “God” (ὁ Θεòς) in John 3:16. And we don’t help ourselves romanticizing and disrespecting that sacred author by imagining that if he somehow heard our Profession of Faith on Sundays he would nod his head and say, “Yeah! That is what I meant to say!”

The Obvious Meaning of “God” in “John”

None of this phases the fundamentalist, be she Catholic or other. For her, it’s all there, clear and obvious. Scripture to the fundamentalist is like a connect-the-dots to that which they have already reached: certitude. In their box-worlds nothing is vague or unclear or really mysterious. Theology for the fundamentalist is like a mechanical process where everything adds up to their security and superior position.

Were “John,” or anyone in his community, monotheists? Or were they likely henotheists? That’s a big difference from later Christians, folks! We leave the first century without those early Jesus groups answering the big metaphysical questions about Jesus and God. The unpacking took a lot of struggle and a great amount of time.

It’s Obvious God Loves the Whole Wide World, Right?

What could the author of the text we call “John” (aka, the Gospel from outer space) mean by “loved” (ἠγάπησεν)? You can bet it would be nothing like that emotional high felt at the Magic Kingdom when we marvel at the fireworks going off during our perfect Orlando vacation. Different cultures express “love” differently. Collectivists such as “John” see “love” like sticky, in-group-glue or community-adhesion. Is that how 21st century Westerners, individualists, conceive love?

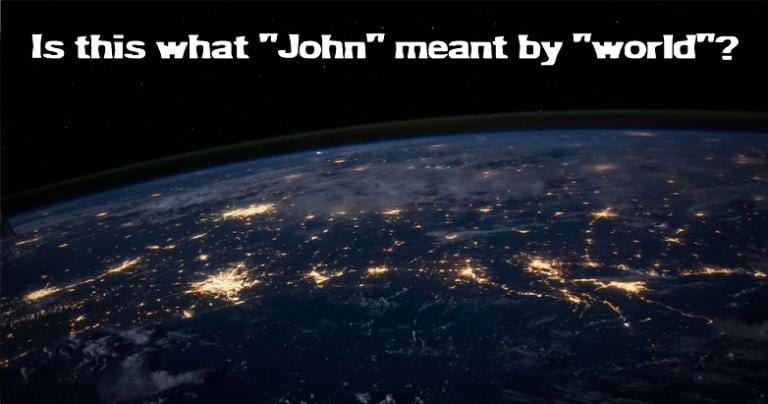

And what about “world” (τòν κόσμον)? What did the author we call “John” mean by it? Did he have our post-Einsteinian cosmology in mind when he wrote of “world”? Could he conceive of cosmos or world in any way like we would in our modern sense, whether in ways geopolitical, environmental, or as a planet?

But all these pesky questions are easy to dismiss for the fundamentalists reading “John!” When they read in English words in that text like God, loved, world, believe or believe in, Son, and thousands of other terms, ethnocentric and anachronistic presumption becomes king! The meanings we Westerners ascribe to those words must be identical with those in the Biblical author’s mind! In’t that obvious? Isn’t that clear? .

…Or Not So Obvious?

But maybe things aren’t so clear and obvious. Maybe instead what we have isn’t clarity but familiarity of the spurious variety? What if we looked beyond our American glasses and actually saw these terms expressing alien social realities?

If I, a 21st century Western Christian, really desired to honor and understand Jesus and my biblical ancestors in the faith, will I plug meanings taken from my United States social system into the words of first century Mediterranean “John”? Depressingly, many are apathetic to these concerns. Loving Jesus and “getting him” often becomes a cheap game of talk.

However, should we instead genuinely seek to understand what the Fourth Gospel called “John” really meant to its original author, editors, and audiences, questions arise. Shouldn’t we be asking: What sort of situation was going on for this community? What were the concerns and crises that shaped this document?

We have a longstanding tradition in the Church for escaping from the holy work of grappling in understanding what the sacred author was really trying to convey into the “spiritual” business of allegorizing passages. In fact, allegory-gone-wild is as old as the Gospels!

Obvious Allegory-Gone-Wild

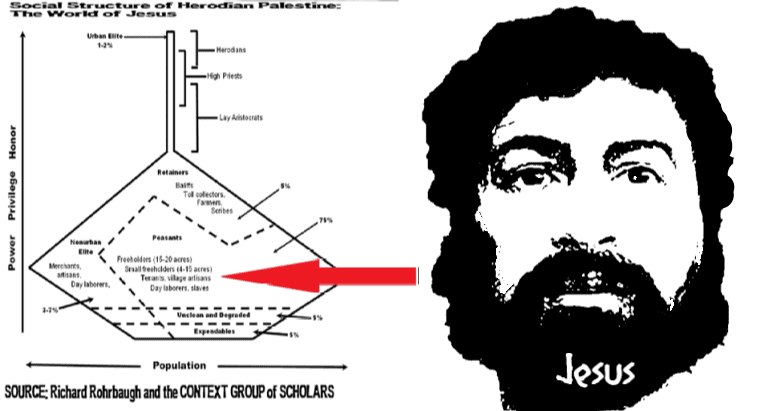

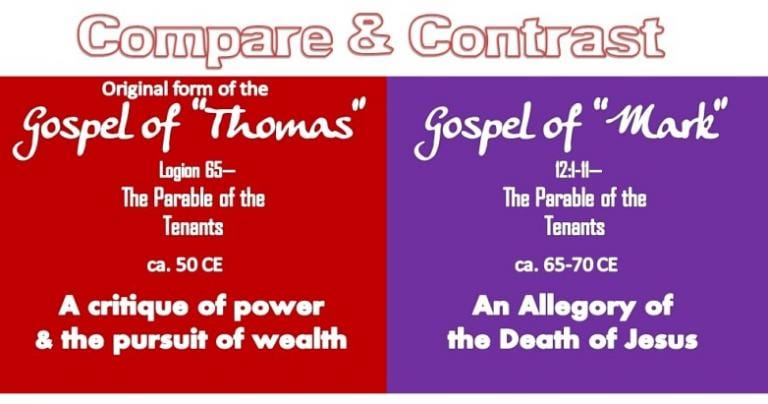

Dr. Richard Rohrbaugh gives us a clear view of the damage this kind of careless reading has done to even a simple parable. Whatever the original form the Parable of the Tenants (Mark 12:1-12) when Jesus told it in the Galilee early first century, by the time it had reached “Mark” it had crossed an impossible social chasm from starving peasantry into the world of elites who could write. Although they were Mediterranean and Israelite, the socio-economic worlds of the anonymous evangelists and peasant Jesus were far apart. The meaning of peasant artisan Jesus’ parables necessarily underwent recontextualization and meaning-loss early on.

An Obvious Allegory about Jesus Messiah

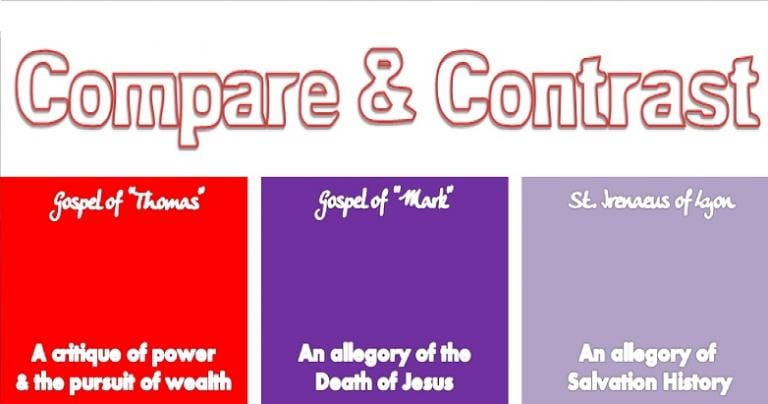

It was obvious to “Mark” (ca. 70 CE) that the tenants in the Parable of the Tenants, which he transformed into an allegory, were wicked men, clearly an analogue for Jerusalem elites who rejected Jesus and put him to death. It was clear and obvious that this story (in the hands of “Mark,” an allegory and no longer a parable) was about the storyteller himself, the Lord Jesus, and his death.

But curiously, not so for the unknown author of the Sayings-Gospel of Thomas (early, pre-Gnostic form, ca. 50 CE). The earliest written version of the Parable of the Tenants is found within this document, Logion 65, written or collected sometime two decades before “Mark” was composed. In that version the usurer who owns the vineyard (no doubt foreclosed ancestral lands of peasants formerly used for subsistence farming and now stolen via kangaroo courts for a cash crop) is hardly an analogue for God! In the “Thomas” version, Jesus is not the son.

This tells us that what “Mark” thought was obvious and clear about the parable wasn’t how Jesus or his peasant audience understood the story when it had been originally told. Besides that, Jesus never told allegories. As Rohrbaugh explains, the historical Jesus understood vineyards as peasant lands stolen from their owners by usurers, greedy elites who bribed courts and destroyed poor people. Language only means what it means where and when it gets used. To reach the evangelist “Mark,” the parable had become an allegory and its meaning therefore changed.

An Obvious Allegory about Salvation History

It was obvious from Scripture to Irenaeus of Lyon (180 CE) that the tenants in the allegorized version of the Parable of the Tenants were all clearly the wicked people through the great sweep of world ages, from Creation to Christ (what 18th century Europeans, familiar with novels and plots and narratives and fact distinct from fiction, would later recontextualize as the Germanism “Salvation History”). For Irenaeus expands cosmically the allegory of “Mark” where the Beloved Son is Jesus Christ.

An Obvious Allegory about Holy Empire

It was obvious from Scripture to Eusebius of Caesarea (324 CE) that the tenants in the parable of the tenants (Mark 12) clearly were the Judeans who rejected the Christ (see his Commentary on Esium 1.39). Living in his glorious time of Imperial Christianity, who could miss that the allegorized parable had to be about the triumph of Christianity with Constantine? And it was as clear as day that the Judeans who had rejected Christ must be those wicked tenants! Clearly the New People of God was the Roman Empire!

Note how far we have traveled from the starving Galilean villages of first century Palestine. Note also that we have reached a time where antisemitism can be backed up with the violent cruelty of imperial might theologically motivated and justified! Onward Christian soliders! With some allegory-gone-wild, it becomes obvious to Medieval Christians from the Gospels read through Eusebius that the tenants (Mark 12) are the Jews. Clearly, thought many, this parable justified killing them. In allegory-gone-wild, the horrors of antisemitism became a noble thing.

An Obvious Allegory about the Human Soul

When he read it, the brilliant Thomas Aquinas (d, 1274) thought it obvious that the vineyard was an analogue for the human soul. It was clearly concerned with Christian self-discipline. Shouldn’t we likewise spiritualize this parable away like Thomas Aquinas did?

An Obvious Allegory Justifying Power, Wealth, Authority, and Cruelty

Dr. Rohrbaugh, a Reformed Christian, explains that Martin Luther (d. 1546) found it obvious reading the Gospels that the tenants in the allegorized parable had to be the Papists (Catholics) and the peasants who rebelled against the German princes. To Luther, the vineyard is the Kingdom of God taken away by God from the Catholics and bestowed upon the German Princes. The allegorical Mark 12 clearly prescribes utterly crushing the German peasants, to Luther.

Consider: in Luther’s reading, Jesus, the peasant day laborer who preached good news to starving villagers, is twisted into blessing the murder of peasants by German elites! This was all most obvious and clear to him.

An Obvious Parable about Cromwell’s Utopia… or King Charles I?

Rohrbaugh explains that when the Puritan and Anti-royalists read their Geneva Bible (with margins stuffed full of their propaganda), it was obvious that the tenants in the allegorized parable of the tenants (Mark 12) were King Charles I (executed 1649) and his magistrates. Clearly, Lord Oliver Cromwell and his anti-royalist/ puritanical utopia could only be the vineyard, God’s very Kingdom on earth! Anyone with sense can see that Mark 12 prescribes decapitating Charles I!

But when the resurgent Anglican Royalists and Charles II (1660) read the “Authorized” King James Version, it was obvious to them that the tenants are the wicked Puritan anti-royalists who martyred Charles I. Clearly to the Royalists, the murdered and martyred king was the “Beloved Son” in the parable! Everyone with common sense should be able to see that is the plain sense of “Mark”!

An Obvious Parable about the Divinely Established British Empire

Rohrbaugh notes that nineteenth century British scholar William Arnot (1865) found it obvious that the tenants in the allegorized parable of the tenants (Mark 12) were those heathen Muslims and Hindus rightly crushed under British colonial rule. To Arnot it was pretty clear that the “Beloved Son” had to be the British Empire! Mark 12 says CRUSH anyone who would dare rebel against the Beloved Son, the British Empire!

Study well the lyrics of this gem of Empire… all theologically justified cruelty via allegory-gone-wild. Empire enslaving poor people backed up by Jesus. It’s clear and obvious, isn’t it?

Obviously, It Is Whatever the Fathers Say It Means!

In the 2000s, Scott Hahn, writing with Curtis Mitch in their “The Gospel of Mark” commentary (pp. 39-40), interpreted the Parable of the Tenants in this way—

“The parable of the Wicked Tenants narrates the history of Israel.”

I should stress that Hahn does not distinguish first century Israel from later Jews. This is important to note. Hahn and Mitch continue,

“The story stresses that God [whom Hahn and Mitch understand as represented by the Landowner] has been patient with his wayward people throughout the ages. The vineyard represents Israel dwelling in the walled city of Jerusalem (Jeremiah 2:21; Hosea 10:1), the tower is the Temple (as in Jewish tradition based on Isaiah 5:1-2), and the tenants are Israel’s leaders stationed in the city. The servants are Old Testament prophets repeatedly sent by God to call for repentance.

“Many prophets were abused and killed (12:5; Luke 13:34), God eventually sent Jesus as the Beloved Son (12:6), whom they also killed (12:8). By adding the detail that the Son is thrust out of the vineyard (12:8), Jesus predicts his Crucifixion outside the city walls of Jerusalem (John 19:20). God will avenge his Son when he sends him to destroy (12:9) the unfaithful of Jerusalem in AD 70…”

What should be obvious to you is Hahn’s supercessionistic reading of Old Testament texts. What should be clear to you are his jigsaw puzzle proof-texting through Gospels that were never meant to combine Voltron-style into a 21st century biography of Jesus. What should be plain is his failure to distinguish ancient Israelites from later Jews.

If only such readings of Scripture were clearly seen as erroneous! Perhaps then theological justification and “Scriptural backing” for some of the worst sins in the history of the Church since the Medieval pogroms would not continue to flourish in our times, as can be seen on hideous display incubating in ultra-conservative blogs and sites!

Obviously One-Part Eusebian Nightmare, Five-Parts Spiritualized

Bishop Robert Barron sees this allegorized parable somewhat differently. Says Barron:

“The parable of the tenants is an allegory that presents the relationship of Israel to Christ, but more than this it reveals a necessary truth about the spiritual life: that we are “tenants” in regards to the gifts that God has given us, and when we construe our relationship to God’s gifts as being that of “owners”, rather than “tenants”, the consequences can be quite dire.”

So a little bit of Eusebian allegory (see above to understand where that leads), and a whole lot of Aquinas-allegory.

An Obvious Parable By, For, and about the American Way

According to biblical scholars like Richard Rohrbaugh, for many American commentators today it is obvious that the tenants of Mark 12 are evil people who want to take away the private property rights of the landowner. It is clear that the landowner is someone who looks an awful lot like an ideal American individualist, who buys American values, and who works very hard for his money. Therefore it is clear to such American commentators that this story must be about the private property rights of the landowner.

Obviously a Tale of Great Sadness

What has happened to Jesus’ story? Something that probably began as a cautionary parable about labor violence as the desperate attempt to respond to crushing injustice has, via allegory-gone-wild, been turned and twisted around to justify the elites. This has been done in the name of Jesus.

We can cut “Mark” and “Matthew” some slack. But once we arrive at imperial cruelty and especially with Luther, the story is turned on its head. Throughout history, what has dominated the interpretation of this story has not been the prepaschal Galilean Jesus and what he intended, but rather the situation of the interpreter.

Context scholar Richard Rohrbaugh reminds us that theologians striving to make Jesus and his stories relevant to Christians alive today is good and needed. But there is always the danger that in doing this noble work, Jesus and his context gets lost, and the whole enterprise becomes an idolatry of self-justification. Why that is a terribly costly violence should be obvious and clear to all who call themselves “followers of Christ.”