Magisterial documents help deepen our appreciation and understanding of the birth accounts in “Matthew” and “Luke.”

“Magisterial” means authoritative, namely authoritative in a teaching way. Sound teaching is needed, particularly when much spurious familiarity and false assumptions abound. It is not magisterial (not official Church teaching) that we Catholics cannot question the historicity of the birth narratives of Matthew 1—2 and Luke 1—2. No magisterial statement is in force demanding Catholics accept these stories as literally historical. We read about this yesterday.

Did It Happen? How Did It Happen?

In fact, when we ask the Gospels historical questions (“Did the first Noel happen at an actual manger?” and “Did three Kings really visit Baby Jesus?”) we are posing modern, Western questions. While these questions are not illegitimate in themselves, it would be wrong and harmful to our study were we to presume they were obsessed over by our Mediterranean biblical ancestors. While 21st century Americans ask: “DID it happen?” ancient Middle Easterners and Mediterranean peoples asked: “What does it MEAN?”

Over the course of Advent and Christmas, Messy Inspirations intends to dive into the two very different Gospel narratives of Matthew 1—2 and Luke 1—2. These are called “Infancy Narratives” and they describe the birth of Jesus from different perspectives. We hope to showcase unique details from each story as well as give insights into why each evangelist included them.

Four magisterial documents concerning church teaching about the Sacred Scriptures should help us on our Christmas adventure.

Magisterial Encyclical Starts a Renaissance

Divino Afflante Spiritu is a papal encyclical by Pope Pius XII. It was issued September 30, 1943. This document ushered in a Renaissance for Catholic Biblical scholarship. Before 1943, especially in reaction to Modernism, Catholic scholars had their hands tied and eyes blindfolded. They could never dare to use the original languages of Scripture or the latest archaeological finds. Scientific critical analysis of the sacred texts were off limits! But Pius XII changed all that by this encyclical, when he commanded using the original languages.

According to Pius XII, Catholic exegetes were to “go back wholly in spirit to those remote centuries of the East with the aid of history, archaeology, ethnology, and other sciences, and accurately

determine what modes of writing … the authors of that ancient time would be likely to use, and in fact did use.” Consequently, this document opened doors that cannot be shut, except by ignorance and fear.

Magisterial at the Highest—Dei Verbum

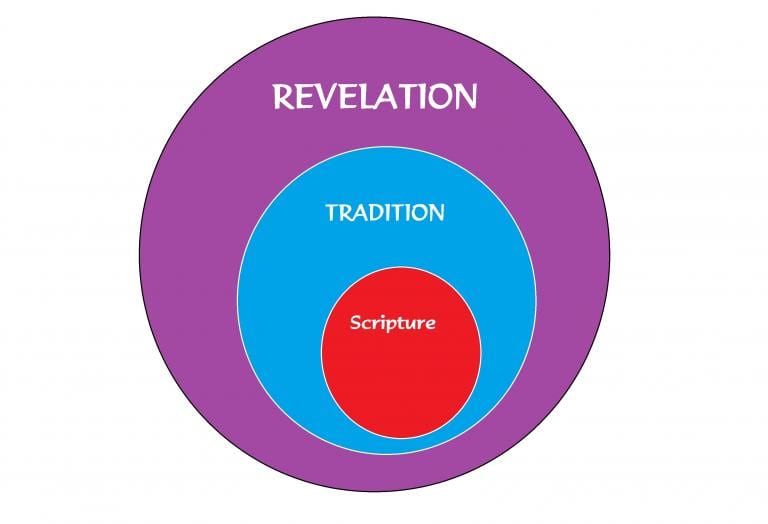

Next we need to consider the most important magisterial document concerning divine revelation, the Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, or Dei Verbum. This was promulgated by Pope Paul VI on November 18, 1965. It presents revelation (or God’s self-disclosure) as being greater than and including Scripture. One might understand it in mathematical terms this way—

Revelation > Tradition (or the Transmission of Divine Revelation) > Scripture.

So revelation is incarnational. It begins with Creation, long before the Catholic Church came on the scene.

According to Dei Verbum, the Bible is not only divine, but also very human. The Scriptures are divine in that they contain things disclosed by God via inspired writing (n. 11). But the Sacred Writings are every bit as human nonetheless, as God’s Word is given through human beings in human fashion (n. 12). Should Bible readers desire to truly ascertain what God has wished to communicate to us, then they should “carefully search out the meaning which the sacred writers really had in mind, that meaning which God had thought well to manifest through the medium of their words” (n. 12).

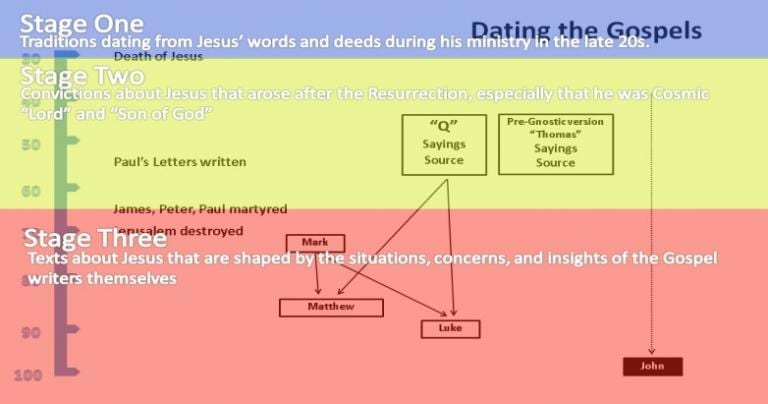

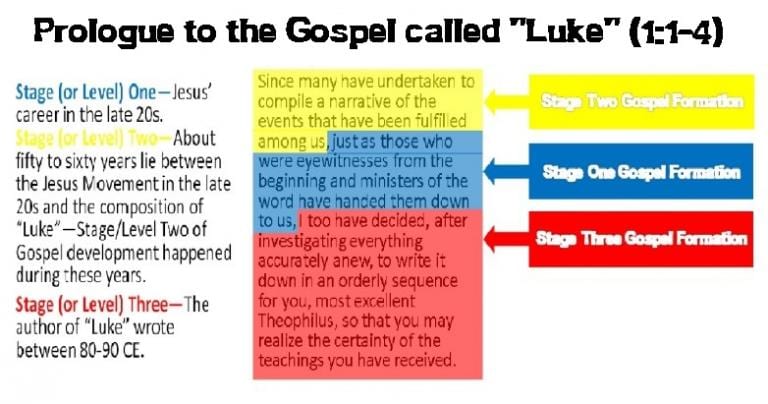

The Pontifical Biblical Commission’s “Instruction Concerning the Historical Truth of the Gospels” (April 21, 1964). This document has its problems but spells out (nn. 6-9) that the Gospels evolved in three distinct stages of development. Both Dei Verbum n. 19 and the Catechism n. 126 state this also. Look here:

We will return to those three stages of development, momentarily.

Magisterial Plagiarism?

Finally we come to the Pontifical Biblical Commission’s “The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church,” issued April 23, 1993. Marvelously, this document condemns no one! Developing from Dei Verbum, it explains that because the Bible is the ‘word of God in human language,’ it got “composed by human authors in all its various parts and in all the sources that lie behind them.”

Therefore, with that in mind, how could Catholic scholars not freely make use of the scientific methods and approaches? Without these, how could they hope to grasp of the meaning of texts in their linguistic, literary, socio-cultural, religious, and historical contexts? How could they explain them without recourse to their sources? Without attending to the personality of each inspired author, can they honestly break open the Word?

John Pilch gives an interesting detail about this maverick document. He says that it couldn’t have been composed without the Context Group of biblical scholars to which he belonged. According to Pilch, the year before its publication, Fr. Domingo Munoz had been sent by the Vatican to spy, er, observe a seminar they were giving in Medina del Campo, Spain. Pilch claimed that the section on socio-cultural interpretation in “The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church” was quite literally a “cut-and-paste job.” Pilch claims that Munoz took detailed notes from talks given by himself and others. According to Pilch, the old Catholic way of “just steal it!” is still in good use.

Magisterial Education

Catholics are without excuse should they remain ignorant of contemporary teaching on Revelation and Scripture. All of these documents are available online. Catholic understanding of the Bible has changed drastically. This profound change is quite recent. These documents help us to see these changes.

More on Those Three Stages

As indicated above, certain magisterial documents acknowledge and explain that the written Gospels contain materials that originated in three distinct first-century time periods or “stages.” These can be found often all appearing in the same biblical passage—

Stage 1: The Jesus Movement

These are traditions dating from Jesus’ words and deeds during his ministry in the late 20s. This is the situation of the prepaschal Jesus. Here we discover the Jesus of history.

Stage 2: Post-Resurrection Apostolic Preaching

Here we see the first interpretations/convictions about the Risen Jesus. It is a stage happening after the Resurrection, in its light. Beliefs in Jesus arise, especially that he was the cosmic “Lord” and “Messiah.” It is in this stage we discover the earliest expressions of the Christ of faith

Stage 3: The Gospels are Composed

The most neglected, yet most important stage of Gospel development, is the third stage. Decades after the death and resurrection, and following the deaths of the apostles and refusal of Israelite theocracy to materialize, Jesus groups are in crisis. To face these new situations and problems, texts get written. They are faith-portraits which present updated memories about the Risen Lord. The Gospels concern Jesus in a way that is shaped by the situations, concerns, and insights of the Gospel writers themselves

What is Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3?

Believing that the Gospels evolved through stages of development is one thing. Determining what in a verse derives from the three stages is another. How do we determine from which stage material found in the Gospels originates? Scholars have worked out various criteria for establishing this in degrees of probability. The following video explains this:

Final Notes

Important take away for all off this—especially concerning our investigation of the Infancy Narratives of Matthew 1—2 and Luke 1—2—is that the Evangelists were not writing “histories,” as we United States people use the term. They were not writing eye-witness, biographical accounts in the 21st century Western sense. So we can eliminate thinking of the Infancy Narratives of Matthew 1—2 and Luke 1—2 in this ethnocentric and anachronistic way.

They wrote stories for ancient Mediterranean Israelites already inside their Jesus groups. The Evangelists were not selling anything. They were not writing these stories for outsiders. Their audience already accepted Jesus as Messiah and Cosmic Lord.

Again an invitation: with all this in mind, familiarize yourselves with the separate stories of Matthew 1—2 and Luke 1—2. Read each by itself. Keep a notepad and pen handy and jot down details particular to each. Ask yourself why “Matthew” leaves out things “Luke” includes, and vice versa.