Mourning the dead was an important and lengthy process for first century Israelites, a process interrupted in the case of the Risen Jesus.

Mourning and celebration are juxtaposed closely in our tradition, even to the breadth of a Holy Saturday, between the Cross of Good Friday and the alleluias of Easter Sunday. The tears of Friday become joyous gladness by Sunday. Of course, everything in our New Testament and our existence as Christians proceeds from Easter. We are an Easter people. But it’s easy to skip over the burial of Jesus and the mourning that ordinarily would follow an Israelite burial, so as to miss out on just how significant resurrection is.

Over several posts I want to explore with you the significance of Israelite burial and mourning custom. The purpose will be so as to better appreciate the heart of Easter. Today we will be looking at the usual process of burial and mourning for first century elite Israelites.

Strange Mourning & Burial Practices!

The Gospels hint at important ancient burial and mourning practices quite remote for U.S. Christians. Consider: What is going on exactly in the various Gospel accounts about Jesus’ burial and the women subsequently going to anoint him? Wasn’t his corpse inaccessible to these women? It was being held in custody under Roman guard, no? Wasn’t it sealed away, locked behind a stone?

Since the Gospels all attest to Jesus’ body being treated thus, how could Mary Magdalene, whether alone (as in John 20:1-2) or in the company of other women (as in the Synoptics—Mark 16:1; Matthew 28:1; Luke 24:1, 9-10) ever hope to reach the body of Jesus, much less anoint it?

Deeper Questions

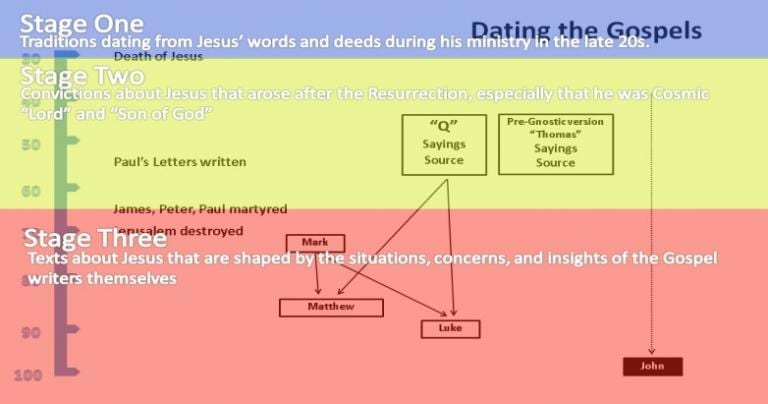

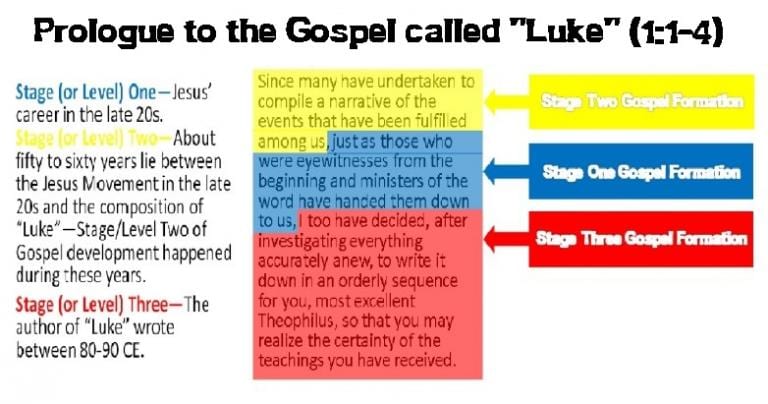

Investigating these questions, diving deep into them, raises many fascinating issues. What about the story of the women going to anoint the dead Jesus is factual/historical (Stage One of Gospel Development), and what about it was theologically crafted later on (Stages Two and Three of Gospel Development)?

Also some pretty heavy theological stuff gets raised—by interrupting the mourning and burial process, what does the resurrections say about the death of Jesus? Was it right and necessary (in accord with God’s will)? Or was it wrong and thus overturned by God?

It will take several posts to explore these questions. First, in order to get there, it is important to understand the meaning of Israelite burial customs and the mourning process of Jesus’ day. This has been preserved for us in ample first century archaeological evidence from Syro-Palestine and subsequent scribal Pharisaic documents. Cultural anthropology and the social sciences help us to sift through and rightly contextualize the data. I will be drawing from the insights and guidance of Context Scholars Bruce Malina and Richard Rohrbaugh here.

Understanding a Collectivistic Mourning Process

We should explain that life for ancient Israelites—all collectivistic, anti-introspective, dyadic personalities—was an existence where everyone lived together. They lived together as a group-self, having one group-conscience. All were embedded into the most significant family male or patriarch.

Therefore first century Israelites ordinarily dwelt together in the patriarchal compound. Within that compound were arranged, endogamous, patrilateral first-cousin marriages. Life was lived patrilocally. This is how things always had been, and would be forever, and I mean forever, as in forever and ever and don’t you DARE even think of changing that! This Israelite existence is basically how it was with all ancient MENA (Middle Eastern North African) peoples and also ancient Mediterraneans. Even today, this remains visible through much of that part of the world.

When I say “forever and ever” I am not exaggerating. This cannot be stressed enough to American individualistic Christians who marry exogamous self-selecting partners and tend to reside with them in neolocal homes. American Christians enjoy making absurd claims that they live in “Biblical” ways and celebrate “Biblical marriage” and how “Bible-based” their families are. But they don’t really know what they are talking about when they do this.

For ancient Israelites and all other Mediterranean peoples, even after death this “embedded dwelling together” continued. In first century Israel everyone got buried together, rotted together, and awaited resurrection together. The domestic religious belief and practice of Ancestorism was therefore hugely important to first century Israelites as it was for all Mediterranean peoples.

Time of Death & Elite Perspective

Unlike Americans (Christian or not, it makes no difference) who understand death as punctiliar, in contrast, ancient Israelites understood death as a lengthy process. So let’s now go over what we know about this process to illuminate things about Jesus’ death and burial.

A word of caution—I mentioned earlier that our sources will be archaeological finds and scribal notes. Please keep in mind that no more than two percent of the total population of Herodian Syro-Palestine were literate. Consequently, I should point out that the Gospel writers belonged to and were sympathetic of the urban elite since “like writes about like.” In other words, whenever anyone writes, they write about what they know.

Since ancient Israelite authors were elites, then they must have had elite concerns, and these are readily discoverable in their writings. But what happens if they should write about a peasant or nothing-person, like the Galilean artisan Jesus? Please be aware that these authors, being far removed from the socio-economic conditions of the Galilee, necessarily were perceiving things by looking over an uncrossable social chasm of extreme difference and experiences!

This seldom-discussed yet crucially important aspect of New Testament analysis applies very much to the Evangelists we call “Mark,” “Matthew,” “Luke,” and “John”! Being literate, their experience was far-removed from the Galilee of Jesus and its illiterate and starving peasantry.

Elite Judaean Funeral

So with that understood, we will now describe burial practices for elite circles in Judaea. Just keep in mind that we are not talking about the non-urban poor like Galilean peasant, day-laborer Jesus. Nor are we talking about what happens to a condemned criminal. But don’t worry—we’ll get there.

Imagine a first century Jerusalem elite has died. Sometime between his final breath and sundown, slaves, overseen by significant family members, would lay out his body on a shelf or slab within the family tomb. Outside Jerusalem, artisans and day laborers had carved this tomb from the abundant limestone bedrock of the surround.

Then the mourning process would commence. First on the agenda was the lengthy funeral. Even far from the grave site, professional mourners could be heard, wailing and weeping, displaying the family honor to all around. Musicians would play instruments employed to induce altered states of consciousness, readily experienced at grave sites for millennia by Mediterranean personalities.

Ancient Israelite Anthropology

Most Mediterraneans in the first century, even most elites, did not hold to what Plato and Aristotle believed about death or about souls separating from bodies. Biblical peoples almost always did not think of themselves as souls that inhabited a body, or that had a body. Rather, they commonly understood that they were a body. In other words, for most Israelites, to be human was to be an animated body rather than an incarnated soul. Therefore the etymology of earthy ha’adam, essentially bodily, is crucial in regarding how Israelites saw being human.

In four days most Israelites believed the life force of the dead person, more a shadowy breath than soul, had left to a place of shadows. Even still after this, female kinfolk continued sitting on the floor for at least a month, mourning. Indeed, throughout the whole year following the deceased’s last gasp of breath, mourning continued, as the body, sealed behind stone, decomposed.

Decomposition is Painful

Often at wakes, Americans look down at the arranged beloved figure in the coffin (a bloodless, organless façade drenched is preserving chemicals) and make comments like, “Well, at least she’s not suffering anymore.” Sentiments like these were most alien to the ancient Israelite mourning experience. In extreme contrast, our Biblical ancestors believed that the snail’s paced process of flesh rotting away was agonizingly painful. For the Israelite, feeling does not end with the last breath. It goes on through decomposition.

However they also considered this painful decomposition process to be expiatory of sins (acts that shamed or dishonored God)! Our ancient Israelite ancestors imagined that a dead Israelite’s evil acts were somehow embedded into his or her flesh. Therefore, they thought, as the flesh excruciatingly dissolved, so too the sins of the deceased also dissolved. Hence, Israelite mourning was a suffering in solidarity with the dead.

Anointing a corpse with perfumes and rubbing salves and aloes on the body were meant to soothe the horrible pangs for a helpless sufferer undergoing the transition of decay. In the first days following the final breath, spending time close to the tomb was to help ease this torturous transformation for the deceased elite. This kind of mourning was the best thing for elites to do for their dead elite kin.

Now consider: if the Gospel writers, themselves elites, spent time writing about the dead Jesus being anointed, especially with costly oils and perfumes, do you think this reflects the experience of Galilean peasant villages or the elite who lived in a Mediterranean polis? Does it reflect stage one of Gospel formation? Or stage three?

Collecting the Bones for Resurrection

Once a year passed, the mourning ritual concluded. By this point, all that would be found in the linen burial cloth would be dusty bones. These bones were important, sacred even. This was because first century Israelites believed that the bones of a dead person held his or her personality and were essential for resurrection (i.e., making a human being into a star).

The Pharisaic belief was that when the God of Israel eventually came to raise the dead person at resurrection, his or her bones would be used as a support structure or scaffolding for the new “sky vault flesh.” Because of this Pharisaic hope, after one year of mourning, the tomb would be opened up, and a key process called ossilegium or “the collection of bones” would commence.

Following one year of purification from sin in the putrefaction of flesh, the bones of the elite dead were collected and placed into a “bone box” called an ossuary. This was a second burial into a second casket. Rohrbaugh and Malina explain that the ossuary was designed to resemble a box for scrolls. The ossuary had to be just long enough to hold the femurs, the longest and strongest bones of the human body. These thigh bones got laid in like scroll spindles. There they would be kept safe until God gave them new sky vault flesh and a new inscription.

Ossuaries We should note that the practice of ossilegium was so widespread in Israel that, despite its associations with resurrection, even high ranking Sadducees like Caiaphas the High Priest had ornate ossuaries.

Rich and Poor Ossuaries

Please take careful note of all this writing symbolism associated with the ossuary and second burial. Again, recall that only two percent of ancient Israelites could read and write. Therefore consider: from what sector does this burial symbolism, associated with scrolls and new inscriptions, originate? From the illiterate Galilean poor? Or from the elite urban population?

The poor also had humble ossuaries. I ought to mention that besides tools for writing, there was also another image and symbolism concerning the femurs and ossuary, more befitting a humbler social status. Some Israelites regarded the thigh bones as loom posts with which God, seen as a weaver, would fashion and spin out a new sky vault body.

Should it be surprising then, given all this writing and weaving symbolism tied up with resurrection, that archaeologists have uncovered many inkwells and spindle whorls inside the excavated tombs?

The Second Burial

After a year of mourning came the Second Burial, a happy day. This day marked the end of the racking pains of the rotting deceased and the finality to the family’s mourning process. On that day the family turned toward the hope of family reunion and resurrection.

But now imagine what would happen if somehow, at any point over this long process, the body vanished. Although difficult for American Christians to imagine it, to lose a body following death would be far more horrific than the death itself! This may give some insight to what Mary Magdalene is emotionally going through in John 20:1-2, 11-18. This is a horror-show, another biblical tale of terror. Because if you don’t have those bones, how can you prepare them for resurrection? All Israelites would understand the terrifying predicament.

Soon, we will explore more on this topic and how the resurrection of Jesus interrupted the mourning process in a most surprising and extraordinary way. We will also look into how it affects the question of whether Jesus’ death was wrong—against the will of God—or right and necessary.